Partisan Congress riots

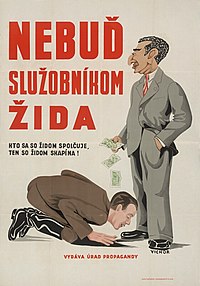

Tensions between Jewish and non-Jewish Slovaks were exacerbated in May 1946 by the passage of an unpopular law that mandated the restitution of Aryanized property and businesses to their original owners.

Despite attempts by the Czechoslovak police to maintain order, ten apartments were broken into, nineteen people were injured (four seriously), and the Jewish community kitchen was ransacked.

[3][4] Between the revolutions of 1848 and the end of the nineteenth century, Pressburg witnessed repeated and extensive anti-Jewish rioting, in 1850, 1882 (in response to the Tiszaeszlár blood libel), 1887, and 1889.

[19] Former partisans, veterans of the Czechoslovak armies abroad, and ex-political prisoners were prioritized for appointment as national administrators[a] of previously Jewish businesses or residences.

[19] Top officials in the Slovak autonomous government, such as Jozef Lettrich and Ján Beharka [cs], did not issue clear condemnations of the attacks and even blamed Jews.

[27] The organizations ÚSŽNO (Central Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Slovakia) and SRP (Association of Racially Persecuted People) advocated for the rights of Holocaust survivors.

[30] In May 1946, the Slovak autonomous government passed the Restitution Act 128/1946, which canceled Aryanizations in cases where the victim was judged to be loyal to the Czechoslovak state.

On 31 July, podplukovník Rudolf Viktorin [sk] of the Czechoslovak police met with ÚSŽNO leaders and told them that he expected trouble from "reactionary elements" at the congress.

Several men identifying themselves as partisans showed up at František Hoffmann's apartment on Kupeckého Street and threatened to shoot him if he refused to open the door.

[41] In the evening on 2 August, Vojtech Winterstein, SRP chairman, called Arnošt Frischer, who led the Council of Jewish Religious Communities in Bohemia and Moravia, telling him that the Jews in the city feared an increase in the rioting.

[49] According to a police report, violence continued until 01:30 on 3 August, when two grenades were thrown into Pavol Weiss' house, where three Jewish families lived, without causing injury.

Slovak politicians Karol Šmidke, Ladislav Holdoš [cs; sk], and Gustáv Husák addressed the demonstrators, ineffectually attempting to calm the situation.

The police and a group of former partisans led by Anton Šagát intervened to stop the rioters, but not before Rybár's personal documents had been stolen along with 5,000 Kčs.

[45] On 4 August, former partisans held a parade at which anti-Jewish slogans were shouted,[50][51] especially by the contingents from Topoľčany, Žilina, Spišská Nová Ves, and Zlaté Moravce.

Possible reasons for this include a belief that crimes committed by partisans should be dealt with internally, the difficulty of arresting armed persons, and the sympathy of some policemen with the rioters.

[45][52] Winterstein criticized the police response, arguing that law enforcement tended to arrive late and release detained persons quickly, who then went on to make additional attacks.

[37][55] Some of the partisans who had been at the congress in Bratislava went to Nové Zámky on 4 August, attacking the Ungar café at 19:30, beating the owner so severely he was unable to work, and stabbing six Jewish patrons.

[57] Slovak historian Ján Mlynárik suggests that the occurrence of similar events in multiple locations in Slovakia may indicate that they were planned in advance.

[53] On 6 August 1946, the state-controlled Slovak News Agency denied the riots had occurred, claiming that foreign newspapers had printed incorrect information.

[58] The next day, the news agency released another report, accusing illegal organizations linked to foreign interests of conspiring to distribute anti-Jewish propaganda to partisans arriving in Bratislava by train.

[61] On 20 August, the government newspaper Národná obroda claimed that Hungarians had colluded with former Hlinka Guardsmen and HSĽS members to cause the riots.

[54] Mlynárik points out that riots also took place in August 1946 in the northern and eastern parts of Slovakia, where Hungarians did not live, belying the official narrative.

[64] On 11 August, Pravda, the official daily of the Communist Party of Slovakia,[63] published an article on the events, blaming "various influential groups" for conspiring with "anti-state elements" and fomenting unrest.

The resulting undated report, by Ján Čaplovič, quoted the Interior Ministry Commissioner of Czechoslovakia, Michal Ferjencik, who blamed Jews for not speaking Slavic languages, failing to reconstruct the country, and trading on the black market.

In September, members of the security forces were threatened with dismissal if they did not act decisively against anti-Jewish riots, and they were ordered to seek out and punish the attackers in previous demonstrations.

[69][70] Due to the government's concern about disturbances during the second anniversary celebrations of the Slovak National Uprising later in August, hundreds of policemen were transferred from Czechia to Slovakia.

[71] In a note dated 10 August, Main Headquarters of National Security (HVNB) claimed that the riots were "orchestrated with the intention of sullying the reputation of the [Czechoslovak] Republic at the [Paris] Peace Conference".

[72] To prevent a reoccurrence of the rioting, the commissioner of internal affairs of the autonomous Slovak government recommended dismissing or arresting members of the security forces who had participated in anti-Jewish actions, and a crackdown on public gatherings.

[u] In September 1946, the Ministry of the Interior announced that Jews who had declared German or Hungarian nationality on prewar censuses would be allowed to retain Czechoslovak citizenship, rather than face deportation.

The riots originated in an altercation at a farmers' market in Stalin Square in which Emilia Prášilová, a pregnant non-Jewish Slovak woman, accused sellers of favoring Jews.