Postwar anti-Jewish violence in Slovakia

Postwar anti-Jewish violence in Slovakia resulted in at least 36 deaths of Jews and more than 100 injuries between 1945 and 1948, according to research by the Polish historian Anna Cichopek.

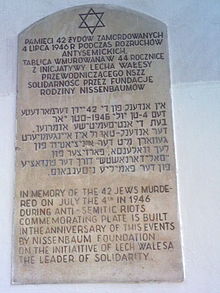

The most notable incidents were the Topoľčany pogrom on 24 September 1945, the Kolbasov massacre in December 1945, and the Partisan Congress riots in Bratislava in early August 1946.

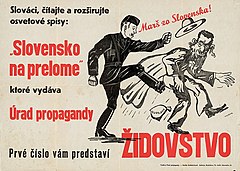

[2][3] Unusually, the Slovak State organized the deportation of 58,000 of its own Jewish citizens to German-occupied Poland in 1942, which was carried out by the paramilitary Hlinka Guard and regular policemen.

[9] The organizations ÚSŽNO (for Jews) and SRP (Association of Racially Persecuted People) formed to advocate for the rights of Jewish survivors.

[14][15] Former partisans, veterans of the Czechoslovak armies abroad, and political prisoners were prioritized for appointment as national administrators[a] of previously Jewish businesses or residences.

[26][27] False claims were made that Jews had not suffered as much as non-Jews during the war and had not participated in the Slovak National Uprising, which further fueled resentment against them.

[29][31] Actual ritual murder libel was rare but occurred, especially in the form of Jews supposedly needing Christian blood in connection to emigration to Israel.

[29] Especially in eastern Slovakia, supporters of the former regime were outraged that the new government considered participation in roundups and deportation of Jews to be a criminal offense.

[33][34] Another issue was the passage of Jewish refugees from Poland and Hungary through Czechoslovakia; these Jews did not speak Czech or Slovak, further inflaming suspicions.

[35] The anti-Jewish policies of the wartime government sharpened categorization along ethnic lines; when victims were attacked because of being Jews, their Jewishness overpowered any other affiliations (such as political, national, or economic).

[36] Czech historian Hana Kubátová points out that these accusations against Jews differed little from classical antisemitism as found in, for example, the eighteenth-century novel René mládenca príhody a skúsenosti [sk] by Jozef Ignác Bajza.

On 22 July, 1,000 people participated in a partisan demonstration at which a man, identified in a police report as Captain Palša, advocated the "cleansing" of collaborators from the area.

Antisemitic slogans were shouted, and some demonstrators went to a nearby bakery where white bread (forbidden by rationing laws) was supposedly being made for Jews.

In July, the rioting spread to the nearby city of Prešov, where non-Jews complained about the deportation of Czechoslovak citizens to the Soviet Union; Jews were accused of supporting Communism.

[42] On Sunday, 23 September 1945, people threw stones at a young Jewish man at a train station and vandalized a house inhabited by Jews in nearby Žabokreky.

[48] On 14 November 1945, a riot occurred in the eastern Slovak town of Trebišov over the refusal of the authorities to distribute shoes to people who did not belong to a recognized trade union.

[50] On 6 December 1945 around 20:00, armed men entered the house of Alexander Stein in Ulič, and murdered him along with his wife and another two Jewish women who were present.

When the SRP came to investigate, it found non-Jewish neighbors stealing belongings from Polák's house, including a cow and a sewing machine.

The presence of the UPA in the area was documented; their modus operandi was to ask locals where Jews and Communists lived, then return at night to attack them.

[50][51] Slovak historian Michal Šmigeľ notes that the police and government tried to downplay local antisemitism and blame incidents on the UPA instead.

He hypothesizes that local police, Communists, or people seeking to acquire Jewish property were responsible for some of the violence, and may have collaborated with the UPA.

[39] Tensions between Jewish and non-Jewish Slovaks were exacerbated in May 1946 by the passage of the Restitution Act 128/1946, an unpopular law that mandated the restoration of Aryanized property and businesses to their original owners.

Despite attempts by the Czechoslovak police to maintain order, ten apartments where were broken into, nineteen people were injured (four seriously), and the Jewish community kitchen was ransacked.

[67] In addition to the riots in Bratislava, other anti-Jewish incidents occurred the same month in several cities and towns in northern, eastern, and southern Slovakia.

[69] Slovak historian Ján Mlynárik suggests that the occurrence of similar events in multiple locations in Slovakia may indicate that they were planned in advance.

[73] The police made up a list of politically unreliable individuals to be arrested if there was any violence, which the Communist Party planned to exploit to increase its power.

The unrest began with a dispute at a farmers' market in Stalin Square, where Emilia Prášilová, a pregnant non-Jewish Slovak woman, accused vendors of showing favoritism towards Jews.

"[80] Stories of anti-Jewish incidents in Slovakia were quickly picked up by the Hungarian press, which passed them to the Jewish media to discredit Czechoslovakia.

[84] Following the departure of most Slovak Jews to the State of Israel and other countries after the 1948 Communist coup—only a few thousand were left by the end of 1949[85][86]—antisemitism transmuted into a political form as evinced in the Slánský trial.

[86] The 2004 film Miluj blížneho svojho ("Love thy neighbor") discussed the riots in Topoľčany and contemporary attitudes towards them, attracting considerable critical attention.