Pascal's triangle

In mathematics, Pascal's triangle is an infinite triangular array of the binomial coefficients which play a crucial role in probability theory, combinatorics, and algebra.

The Persian mathematician Al-Karaji (953–1029) wrote a now-lost book which contained the first description of Pascal's triangle.

[5][6][7] In India, the Chandaḥśāstra by the Indian lyricist Piṅgala (3rd or 2nd century BC) somewhat crypically describes a method of arranging two types of syllables to form metres of various lengths and counting them; as interpreted and elaborated by Piṅgala's 10th-century commentator Halāyudha his "method of pyramidal expansion" (meru-prastāra) for counting metres is equivalent to Pascal's triangle.

[1] Pascal's triangle was known in China during the 11th century through the work of the Chinese mathematician Jia Xian (1010–1070).

[10] In Europe, Pascal's triangle appeared for the first time in the Arithmetic of Jordanus de Nemore (13th century).

[12] Petrus Apianus (1495–1552) published the full triangle on the frontispiece of his book on business calculations in 1527.

[13] Michael Stifel published a portion of the triangle (from the second to the middle column in each row) in 1544, describing it as a table of figurate numbers.

[12] Gerolamo Cardano also published the triangle as well as the additive and multiplicative rules for constructing it in 1570.

[14] In this, Pascal collected several results then known about the triangle, and employed them to solve problems in probability theory.

To see how the binomial theorem relates to the simple construction of Pascal's triangle, consider the problem of calculating the coefficients of the expansion of

It is not difficult to turn this argument into a proof (by mathematical induction) of the binomial theorem.

Rather than performing the multiplicative calculation, one can simply look up the appropriate entry in the triangle (constructed by additions).

First, polynomial multiplication corresponds exactly to discrete convolution, so that repeatedly convolving the sequence

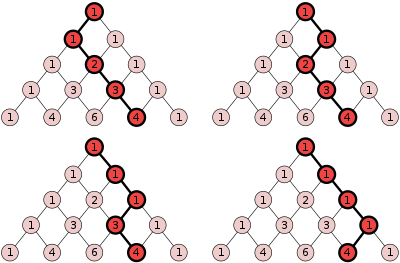

Place these dots in a manner analogous to the placement of numbers in Pascal's triangle.

and obtain subsequent elements by multiplication by certain fractions: For example, to calculate the diagonal beginning at

Just as each row, n, starting at 0, of Pascal's triangle corresponds to an (n-1)-simplex, as described below, it also defines the number of named basis forms in n dimensional Geometric algebra.

The binomial theorem can be used to prove the geometric relationship provided by Pascal's triangle.

[23] This same proof could be applied to simplices except that the first column of all 1's must be ignored whereas in the algebra these correspond to the real numbers,

To get the value that resides in the corresponding position in the analog triangle, multiply 6 by 2position number = 6 × 22 = 6 × 4 = 24.

Each row of Pascal's triangle gives the number of vertices at each distance from a fixed vertex in an n-dimensional cube.

After suitable normalization, the same pattern of numbers occurs in the Fourier transform of sin(x)n+1/x.

Then the result is a step function, whose values (suitably normalized) are given by the nth row of the triangle with alternating signs.

[25] For example, the values of the step function that results from: compose the 4th row of the triangle, with alternating signs.

In fact, the sequence of the (normalized) first terms corresponds to the powers of i, which cycle around the intersection of the axes with the unit circle in the complex plane:

Pascal's triangle may be extended upwards, above the 1 at the apex, preserving the additive property, but there is more than one way to do so.

[28] Isaac Newton once observed that the first five rows of Pascal's triangle, when read as the digits of an integer, are the corresponding powers of eleven.

[31][32] To better understand the principle behind this interpretation, here are some things to recall about binomials: By setting the row's radix (the variable

The twelfth row denotes the product: with compound digits (delimited by ":") in radix twelve.

are compound because these row entries compute to values greater than or equal to twelve.

from its leftmost digit up to, but excluding, its rightmost digit, and use radix-twelve arithmetic to sum the removed prefix with the entry on its immediate left, then repeat this process, proceeding leftward, until the leftmost entry is reached.