Passenger pigeon

Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus coined the binomial name Columba macroura for both the mourning dove and the passenger pigeon in the 1758 edition of his work Systema Naturae (the starting point of biological nomenclature), wherein he appears to have considered the two identical.

The oldest known fossil of the genus is an isolated humerus (USNM 430960) known from the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina in sediments belonging to the Yorktown Formation, dating to the Zanclean stage of the Pliocene, between 5.3 and 3.6 million years ago.

[16] The passenger pigeon differed from the species in the genus Zenaida in being larger, lacking a facial stripe, being sexually dimorphic, and having iridescent neck feathers and a smaller clutch.

In a 2002 study by American geneticist Beth Shapiro et al., museum specimens of the passenger pigeon were included in an ancient DNA analysis for the first time (in a paper focusing mainly on the dodo), and it was found to be the sister taxon of the cuckoo-dove genus Macropygia.

Robert W. Shufeldt found little to differentiate the bird's osteology from that of other pigeons when examining a male skeleton in 1914, but Julian P. Hume noted several distinct features in a more detailed 2015 description.

The coracoid bone (which connects the scapula, furcula, and sternum) was large relative to the size of the bird, 33.4 mm (1.31 in), with straighter shafts and more robust articular ends than in other pigeons.

[24][42][43] In 1911, American behavioral scientist Wallace Craig published an account of the gestures and sounds of this species as a series of descriptions and musical notations, based on observation of C. O. Whitman's captive passenger pigeons in 1903.

Craig compiled these records to assist in identifying potential survivors in the wild (as the physically similar mourning doves could otherwise be mistaken for passenger pigeons), while noting this "meager information" was likely all that would be left on the subject.

[45][46][47] It has been suggested that some of these extralimital records may have been due to the paucity of observers rather than the actual extent of passenger pigeons; North America was then unsettled country, and the bird may have appeared anywhere on the continent except for the far west.

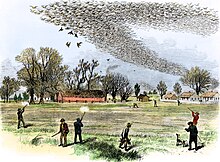

[24] In his 1831 Ornithological Biography, American naturalist and artist John James Audubon described a migration he observed in 1813 as follows: I dismounted, seated myself on an eminence, and began to mark with my pencil, making a dot for every flock that passed.

In a short time finding the task which I had undertaken impracticable, as the birds poured in in countless multitudes, I rose and, counting the dots then put down, found that 163 had been made in twenty-one minutes.

The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse; the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow, and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose ...

[54] A study released in 2018 concluded that the "vast numbers" of passenger pigeons present for "tens of thousands of years" would have influenced the evolution of the tree species whose seeds they ate.

White oak, in contrast, with its seeds sized consistently in the edible range, evolved an irregular masting pattern that took place in the fall, when fewer passenger pigeons would have been present.

[70] With the large numbers in passenger pigeon flocks, the excrement they produced was enough to destroy surface-level vegetation at long-term roosting sites, while adding high quantities of nutrients to the ecosystem.

Because of this—along with the breaking of tree limbs under their collective weight and the great amount of mast they consumed—passenger pigeons are thought to have influenced both the structure of eastern forests and the composition of the species present there.

[72] To help fill that ecological gap, it has been proposed that modern land managers attempt to replicate some of their effects on the ecosystem by creating openings in forest canopies to provide more understory light.

[24] After the disappearance of the passenger pigeon, the population of another acorn feeding species, the white-footed mouse, grew exponentially because of the increased availability of the seeds of the oak, beech, and chestnut trees.

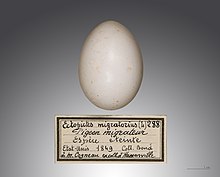

The crop was described as being capable of holding at least 17 acorns or 28 beechnuts, 11 grains of corn, 100 maple seeds, plus other material; it was estimated that a passenger pigeon needed to eat about 61 cm3 (3.7 in3) of food a day to survive.

[80] The colonies, which were known as "cities", were immense, ranging from 49 ha (120 acres) to thousands of hectares in size, and were often long and narrow in shape (L-shaped), with a few areas untouched for unknown reasons.

[52] John James Audubon described the courtship of the passenger pigeon as follows: Thither the countless myriads resort, and prepare to fulfill one of the great laws of nature.

This example strikingly shows us that the procuring a constant supply of wholesome food is almost the sole condition requisite for ensuring the rapid increase of a given species, since neither the limited fecundity, nor the unrestrained attacks of birds of prey and of man are here sufficient to check it.

The sheer number of juveniles on the ground meant that only a small percentage of them were killed; predator satiation may therefore be one of the reasons for the extremely social habits and communal breeding of the species.

[69] For fifteen thousand years or more before the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, passenger pigeons and Native Americans coexisted in the forests of what would later become the eastern part of the continental United States.

The naturalists Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon both witnessed large pigeon migrations first hand, and published detailed accounts wherein both attempted to deduce the total number of birds involved.

[144] For many years, the last confirmed wild passenger pigeon was thought to have been shot near Sargents, Pike County, Ohio on March 24, 1900, when a boy named Press Clay Southworth killed a female bird with a BB gun.

[146][147] On May 18, 1907, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt claimed to have seen a "flock of about a dozen two or three times on the wing" while on retreat at his cabin in Pine Knot, Virginia, and that they lit on a dead tree "in such a characteristically pigeon-like attitude"; this sighting was corroborated by a local gentleman whom he had "rambled around with in the woods a good deal" and whom he found to be "a singularly close observer.

[155] Recognizing the decline of the wild populations, Whitman and the Cincinnati Zoo consistently strove to breed the surviving birds, including attempts at making a rock dove foster passenger pigeon eggs.

Incidentally, the last specimen of the extinct Carolina parakeet, named "Incus," died in Martha's cage in 1918; the stuffed remains of that bird are exhibited in the "Memorial Hut".

[38][162] The main reasons for the extinction of the passenger pigeon were the massive scale of hunting, the rapid loss of habitat, and the extremely social lifestyle of the bird, which made it highly vulnerable to the former factors.