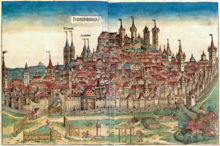

Patriciate (Nuremberg)

From about the middle of the 14th century, economic activities, long-distance trade, mining enterprises and financial transactions of the Nuremberg patricians caused the city and country nobility to increasingly distance themselves from each other.

After the fall of the Hohenstaufen Empire around 1250, families of the imperial ministers from the surrounding area, such as the Pfinzing, Stromer, Haller, Muffel [de] or Groß [de] from the imperial estate (Terra Imperii) they had previously managed, moved into the city, while the former governors of the Hohenstaufen emperors, the burgraves of Nuremberg from the House of Hohenzollern, appropriated large territories in the area around Nuremberg.

After the Burggrafenburg was destroyed by Duke Ludwig VII of Bavaria-Ingolstadt in 1420, the Hohenzollern sold the castle, the surrounding area, and the burgrave office to the city council in 1427, thus finally leaving Nuremberg.

In later times, in particular, some craftsmen's guilds had a certain say in the matter, but never (unlike in cities under Magdeburg or Luebian law, for example ) became part of the circle of actual councilors.

No family was allowed to have more than two members in the council (senators), membership was mostly lifelong, but the councilors were formally re-elected every year in May, later on, the first Tuesday after Easter.

The "older mayors" again became a Septemvirale elected, seven people who formed the actual government of the city and were also called the College of Elderly Men.

Other honorary posts were the “Crown Guardian and Custodian of Imperial Regalia ” and the “Caretaker of the Twelve Brothers House Foundations ”.

As a rule, the new city nobility achieved great wealth through trade, especially with spices and cloths, with trade connections reaching as far as Cologne and Flanders, Lyon, Bologna, and Venice, also to Bohemia, Austria, and Hungary, furthermore through profitable investments in mining, especially in the Upper Palatinate, Thuringia, and Tyrol, as well as through financial transactions.

Patricians were merchants, but they devoted themselves - in contrast to those who sold "by yard, pound and lot " - exclusively to wholesale and long-distance trade.

The land-based noble families of the Franconian knight circle, who lived on the rather modest taxes from their manors, provided they did not hold lucrative court offices or military positions, often took credit from the rich Nuremberg patricians.

In return, however, they denied their equality and thus also their ability to become a pen and tournament, since in their eyes the merchants no longer led a knightly way of life and therefore, regardless of their sometimes aristocratic origins, would have "forfeited" their class affiliation.

These in turn fought - in league with other cities and the princes - the emerging robber barons of the impoverished landed gentry, such as the Schnapphahn Thomas von Absberg, who had several Nuremberg merchants on his conscience, in the Franconian War of 1523.

Since the aristocracy did not allow the patricians to attend the aristocratic tournaments, the patricians' sons regularly and almost demonstratively carried out so-called " journeyman's stings ", festive knightly lance stings on the large market (today the main market) to underline their rank, for the last time in the year 1561.

Connubium with the landed gentry took place rather seldom, not only because of the class reservations of the knight families but also because their possessions were fief-bound and they, therefore, could not offer the merchants any increase in their wealth.

Only the Fütterers from the craftsmen's class managed to become members of the Inner Council, after they had achieved considerable wealth through financial transactions and publishing.

Like the merchant councillors of most other German imperial cities, Nuremberg's patrician families gradually embraced the Protestant faith after the Reformation in 1517, although some were initially hesitant.

As early as 1516, Luther's teacher Johann von Staupitz had made an impression on notable citizens through his sermons in Nuremberg.

However, in order to be able to take office with the knightly canton, patricians had to give up their citizenship, such as Johann Philipp Geuder (1597-1650), who even became director of the imperial knighthood in Franconia, Swabia and on the Rhine.

The social demarcations were precisely defined by title, clothing and living expenses and were regulated by the authorities, for example in dress codes.

The second estate was formed by the big merchants and the important jurist families, who were represented in the Larger Council and were later also called "respectability".

Highly artistic craftsmen such as Dürer, Veit Stoß and Adam Kraft created great works, and the technical inventiveness became known as Nuremberg wit.

Her sons took on the foreign court and military services, others turned to the Frankish imperial knighthood, giving up their civil rights after they had acquired manors with a corresponding status.

Towards the end of the 16th century, the previous trade flows from the Levant, via Italy and the Alps to the southern German imperial cities, had shifted to the north.

The last council dynasties still active in long-distance trade, the Tucher and Imhoff, who were particularly involved in the import of saffron, and the Pfinzing, also finally withdrew to their country estates.

However, when individual families were no longer able to maintain the patrician level and moved professionally and maritally into the lower estates, as the Schürstabs did in the 17th century, they were expelled from the patriciate.

The Thirty Years' War washed many Protestant exiles from the Habsburg hereditary lands (Austria, Bohemia and Hungary) into the city, among them numerous noble families who had lost their domestic property through sale or expropriation.

Oberbürg Castle in Laufamholz became the social center of the Austrian religious refugees from 1637 under the Khevenhüllers and their heirs, especially Countess Margaretha Susanna von Polheim from 1693 to 1721.

The deserving citizen, merchant and patron of the arts Paul Wolfgang Merkel (1756-1820), who bought up numerous art treasures from patrician families during the difficult period of the decline of the council rule, also resorted to the surviving institute of the family foundation in order to preserve his estate, which today forms the basis of the Germanic National Museum.

There and on such patrician estates, which have always been passed on until today, there are still numerous testimonies of patrician culture, for example in the Nuremberg Tucherschloss and in the Neunhof Castle near Nuremberg (both private museums) and on family estates such as Eschenbach, Diepoltsdorf, Fischbach, Großgründlach, Grünsberg, Haimendorf, Heroldsberg, Kirchensittenbach, Kugelhammer, Lichtenhof, Neunhof/Lauf, Simmelsdorf, Schwarzenbruck and Weiherhaus.

The old Nuremberg churches, first and foremost the Sebaldkirche and the Lorenzkirche, are also filled with endowments (altars, windows, statues, paintings, epitaphs and funerary shields) of the council families.