Paulina Luisi

However, she frequently clashed with other major figures in the movement, including members of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) such as Carrie Chapman Catt and Bertha Lutz.

Several prominent Uruguayan advocacy organizations were founded with Luisi's support, including the Unión Nacional de Telefonistas (transl.

[1] Her mother, Maria Teresa Josefina Janicki, was a women's suffrage activist of Polish descent, and her father, Angel Luisi, was a socialist and educator of Italian ancestry.

[2][3] Shortly after her birth, the family moved to Uruguay, where they worked as teachers and founded multiple educational establishments, including the Luisi Institute, the Centro Liberal (transl.

In a letter dated May 1, 1907, Eyle encouraged Luisi and her female colleagues in the university to form an Uruguayan branch of the Universitarias, stating that “although there aren’t many of you now, you will always be the nucleus around which others will come together”.

[7] [Feminism demonstrates that] woman is something more than material created to serve and obey man like a slave, that she is more than a machine to produce children and care for the home; that women have feelings and intellect; that it is their mission to perpetuate the species and this must be done with more than the entrails and the breasts; it must be done with a mind and a heart prepared to be a mother and an educator; that she must be the man’s partner and counselor not his slave.

[13] Because of these divisions, Luisi helped to found the Alianza de Mujeres para los Derechos Femeninos, which split off from CONAMU in 1919.

[15] She specifically opposed the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt and Bertha Lutz, whose attitudes toward Latin American feminists she viewed as being condescending and imperialistic.

As she became more distant from the IWSA, Luisi began associating more closely with the Liga Internacional de Mujeres Ibéricas e Hispanoamericanas (transl.

[20] Luisi was strongly opposed to sex work, viewing it as a degrading "social evil" according to historian Magaly Rodriguez Garcia.

[21] In 1919, Luisi delivered a well-known lecture at the University of Buenos Aires titled "The White Slave Trade and the Problem of Reglamentation".

She also collaborated with the Municipal Council of Buenos Aires in 1919 to outlaw brothels and provide work opportunities, legal protection, and hostels for sex workers seeking to leave the trade.

[4] While there, she proposed the demographic separation of men and women and of different age groups in data about human trafficking so that it would better reflect the vulnerability of women and children to being trafficked, noting in her proposal that "a large number of girl emigrants are sent to South America from countries like Poland, Russia, Spain and Italy for immoral purposes, under the pretext of being hired for ordinary domestic work".

[23] The proposal was ultimately withdrawn, but the International Labour Organization did promise that it would coordinate with the advisory committee on more precise age and sex classifications.

[25] On air, Luisi urged feminists to remain active, arguing that women could make a difference acting as "mediators and peacemakers".

[26] Luisi adopted the nickname "Abuela" while hosting, giving her a sense of authenticity and authority that resonated with women in Uruguay.

She also opposed the Uruguayan "Revolution of March" led by Gabriel Terra in 1933, briefly fleeing to Europe but returning to Uruguay shortly after.

Union of Women Against War), an Uruguayan branch of the Comité Mondial des Femmes Contre la Guerre et le Fascisme (CMF).

She also collaborated with various communist-aligned groups, viewing the rise of fascism as a means for capitalists to maintain control over the working class.

She also helped support Terra's ouster in 1938, though she expressed concern that Uruguay still "suffer[ed] from a de facto government which leans toward fascism".

[1] Her feminist views were influenced by figures within the Western liberal tradition, including Olympe de Gouges, the writer of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, and Josephine Butler, the 19th-century English moral reformer.

[31] Butler's fight against the Contagious Disease Act of 1864 and her foundation of the International Abolitionist Federation (IAF) in Geneva to curb the white slave trade was particularly inspiring to Luisi.

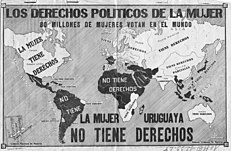

[8] In addition to fighting for women’s rights in Uruguay, Luisi aspired to create a Pan-American feminist movement that would benefit all countries in the Americas.

She espoused an ideal of "moral unity", which was characterized by its opposition to sex work and the spread of venereal diseases, as well as its general concern with elevating the role of women in society.