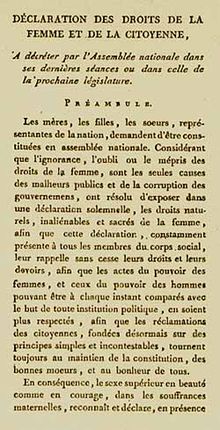

Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

By publishing this document on 15 September, de Gouges hoped to expose the failures of the French Revolution in the recognition of gender equality.

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman is significant because it brought attention to a set of what would later be known as feminist concerns that collectively reflected and influenced the aims of many French Revolutionaries and other contemporaries.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted in 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée nationale constituante), during the French revolution.

[1] The Declaration exposed inconsistencies of laws that treated citizens differently on the basis of sex, race, class, or religion.

[citation needed] Olympe de Gouges was a French playwright and political activist whose feminist and abolitionist writings reached large audiences.

[6] For Gouges there was a direct link between the autocratic monarchy in France and the institution of slavery, she argued that "Men everywhere are equal… Kings who are just do not want slaves; they know that they have submissive subjects".

[8] Gouges wrote her famous Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen shortly after the French Constitution of 1791 was ratified by King Louis XVI, and dedicated it to his wife, Queen Marie Antoinette.

Like men who could not pay the poll tax, children, domestic servants, rural day-laborers, slaves, Jews, actors, and hangmen, women had no political rights.

She demands that her reader observe nature and the rules of the animals surrounding them – in every other species, sexes coexist and intermingle peacefully and fairly.

She asks why humans cannot act likewise and demands (in the preamble) that the National Assembly decree the Declaration a part of French law.

According to her biographer, Olivier Blanc, de Gouges maintained that this article be included to explain to men the benefit they would receive from support of this Declaration despite the advice to her of the Society of the Friends of Truth.

She goes on to describe that "marriage is the tomb of trust and love" and implores men to consider the morally correct thing to do when creating the framework for the education of women.

[13] De Gouges then writes a framework for a social contract (borrowing from Rousseau) for men and women, and goes into details about the specifics of the legal ramifications and equality in marriage.

In many ways, she reformulates Rousseau's Social Contract with a focus that obliterates the gendered conception of a citizen and creates the conditions that are necessary for both parties to flourish.

"[13] In response to the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, many of the radicals of the Revolution immediately suspected de Gouges of treason.

After de Gouges attempted to post a note demanding a plebiscite to decide between three forms of government (which included a Constitutional monarchy), the Jacobins quickly tried and convicted her of treason.

[12] De Gouges was a strict critic of the principle of equality touted in Revolutionary France because it gave no attention to whom it left out, and she worked to claim the rightful place of women and slaves within its protection.

By writing numerous plays about the topics of black and women's rights and suffrage, the issues she brought up were spread not only through France, but also throughout Europe and the newly created United States of America.

[12] In the UK, Mary Wollstonecraft was prompted to write A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects in 1792.

Wollstonecraft wrote the Rights of Woman to launch a broad attack against sexual double standards and to indict men for encouraging women to indulge in excessive emotion.

The singly most common site of institutionalized gender inequality, marriage created the conditions for the development of women's unreliability and capacity for deception.