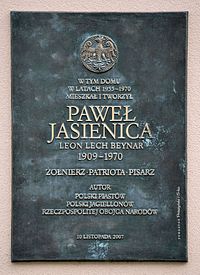

Paweł Jasienica

Paweł Jasienica was the pen name of Leon Lech Beynar (10 November 1909 – 19 August 1970), a Polish historian, journalist, essayist and soldier.

Near the end of the war, he was also working with the anti-Soviet resistance, which later led to him taking up a new name, Paweł Jasienica, to hide from the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland.

He was subject to significant invigilation (oversight) by the security services, and his second wife was in fact an agent of the communist secret police.

His paternal grandfather, Ludwik Beynar, fought in the January Uprising and married a Spanish woman, Joanna Adela Feugas.

[2] Beynar's family lived in Russia and Ukraine—they moved from Simbirsk to a location near Bila Tserkva and Uman, then to Kyiv until the Russian Revolution of 1917, after which they decided to settle in the independent Poland.

[1] During World War II, Beynar was a soldier in the Polish Army, fighting the German Wehrmacht when it invaded Poland in September 1939.

[2] He joined the Polish underground organization, "Związek Walki Zbrojnej" (Association for Armed Combat), later transformed into the "Armia Krajowa" ("AK"; the Home Army), and continued the fight against the Germans.

[3][5][7] For a while, he was an aide to Major Zygmunt Szendzielarz (Łupaszko) and was member of the anti-Soviet resistance, Wolność i Niezawisłość (WiN, Freedom and Independence).

[1][7] After recovering from his wounds in 1945, Beynar decided to leave the resistance, and instead began publishing in an independent Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny.

[1][3][4] It was then that he took the pen-name Jasienica (from the name of the place where he had received treatment for his injuries) in order not to endanger his wife, who was still living in Soviet-controlled Vilnius, Lithuania.

[2] His funeral was attended by many dissidents and became a political manifestation; Adam Michnik recalls seeing Antoni Słonimski, Stefan Kisielewski, Stanisław Stomma, Jerzy Andrzejewski, Jan Józef Lipski and Władysław Bartoszewski.

[1] Throughout his life he avoided writing about modern history, to minimize the influence that the official, communist Marxist historiography would have on his works.

His other popular historical books include Trzej kronikarze, (Three chroniclers; 1964), a book about three medieval chroniclers of Polish history (Thietmar of Merseburg, Gallus Anonymus and Wincenty Kadłubek), in which he discusses the Polish society through ages;[19] and Ostatnia z rodu (Last of the Family; 1965) about the last queen of the Jagiellon dynasty, Anna Jagiellonka.

[10] In addition to historical books, Jasienica, wrote a series of essays about archeology – Słowiański rodowód (Slavic genealogy; 1961) and Archeologia na wyrywki.

[19] Hungarian historian Balázs Trencsényi notes that "Jasienica's impact of the formation of the popular interpretation of Polish history is hard to overestimate".

[16] British historian Norman Davies, himself an author of a popular account of Polish history (God's Playground), notes that Jasienica, while more of "a historical writer than an academic historian", had "formidable talents", gained "much popularity" and that his works would find no equals in the time of communist Poland.

[18] Samsonowicz notes that Jasienica "was a brave writer", going against prevailing system, and willing to propose new hypotheses and reinterpret history in innovative ways.

[10] Ukrainian historian Stephen Velychenko also positively commented on Jasienica's extensive coverage of the Polish-Ukrainian history.