Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance historian Giorgio Vasari used the term rinascita ("rebirth") in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects in 1550, but the concept became widespread only in the 19th century, after the work of scholars such as Jules Michelet and Jacob Burckhardt.

[2] The Florentine Republic, one of the several city-states of the peninsula, rose to economic and political prominence by providing credit for European monarchs and by laying down the groundwork for developments in capitalism and in banking.

[3] Renaissance culture later spread to Venice, the heart of a Mediterranean empire and in control of the trade routes with the east since its participation in the Crusades and following the journeys of Marco Polo between 1271 and 1295.

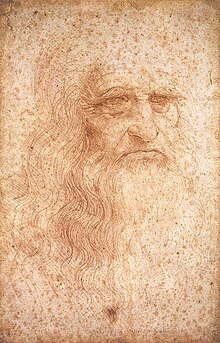

Italian Renaissance art exercised a dominant influence on subsequent European painting and sculpture for centuries afterwards, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Donatello, Giotto, Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Titian.

From France, Germany, and the Low Countries, through the medium of the Champagne fairs, land and river trade routes brought goods such as wool, wheat, and precious metals into the region.

By the 14th century, the city of Venice had become an emporium for lands as far as Cyprus; it boasted a naval fleet of over 5000 ships thanks to its arsenal, a vast complex of shipyards that was the first European facility to mass-produce commercial and military vessels.

[8] In particular, Florence became one of the wealthiest of the cities of Northern Italy, mainly due to its woollen textile production, developed under the supervision of its dominant trade guild, the Arte della Lana.

The rediscovery of Vitruvius meant that the architectural principles of Antiquity could be observed once more, and Renaissance artists were encouraged, in the atmosphere of humanist optimism, to excel in the achievements of the Ancients, like Apelles, of whom they read.

During this period, the modern commercial infrastructure developed, with double-entry book-keeping, joint stock companies, an international banking system, a systematized foreign exchange market, insurance, and government debt.

Those who grew extremely wealthy in a feudal state ran the constant risk of running afoul of the monarchy and having their lands confiscated, as famously occurred to Jacques Cœur in France.

[20][21][22][23] One of the greatest achievements of Italian Renaissance scholars was to bring this entire class of Greek cultural works back into Western Europe for the first time since late antiquity.

He launched a long series of wars, with Milan steadily conquering neighbouring states and defeating the various coalitions led by Florence that sought in vain to halt the advance.

On land, these wars were primarily fought by armies of mercenaries known as condottieri, bands of soldiers drawn from around Europe, but especially Germany and Switzerland, led largely by Italian captains.

On land, decades of fighting saw Florence, Milan, and Venice emerge as the dominant players, and these three powers finally set aside their differences and agreed to the Peace of Lodi in 1454, which saw relative calm brought to the region for the first time in centuries.

At the beginning of the 15th century, adventurers and traders such as Niccolò Da Conti (1395–1469) travelled as far as Southeast Asia and back, bringing fresh knowledge on the state of the world, presaging further European voyages of exploration in the years to come.

Smaller courts brought Renaissance patronage to lesser cities, which developed their characteristic arts: Ferrara, Mantua under the Gonzaga, and Urbino under Federico da Montefeltro.

Examples of individuals who rose from humble beginnings can be instanced, but Burke notes two major studies in this area that have found that the data do not clearly demonstrate an increase in social mobility.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India, and from that date the primary route of goods from the Orient was through the Atlantic ports of Lisbon, Seville, Nantes, Bristol, and London.

The 1250s saw a major change in Italian poetry as the Dolce Stil Novo (Sweet New Style, which emphasized Platonic rather than courtly love) came into its own, pioneered by poets like Guittone d'Arezzo and Guido Guinizelli.

The political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli's most famous works are Discourses on Livy, Florentine Histories and finally The Prince, which has become so well known in modern societies that the word Machiavellian has come to refer to the cunning and ruthless actions advocated by the book.

The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and continued up to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the invention of printing democratized learning and allowed a faster propagation of new ideas.

The key ideas that he explored – classicism, the illusion of three-dimensional space and a realistic emotional context – inspired other artists such as Masaccio, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.

[64] The Holy Trinity fresco in the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella, for example, looks as if it is receding at a dramatic angle into the dark background, while single-source lighting and foreshortening appear to push the figure of Christ into the viewer's space.

[65] While mathematical precision and classical idealism fascinated painters in Rome and Florence, many Northern artists in the regions of Venice, Milan and Parma preferred highly illusionistic scenes of the natural world.

There has been much debate as to the degree of secularism in the Renaissance, which had been emphasized by early 20th-century writers like Jacob Burckhardt based on, among other things, the presence of a relatively small number of mythological paintings.

[69] The period known as the High Renaissance of painting was the culmination of the varied means of expression[70] and various advances in painting technique, such as linear perspective,[71] the realistic depiction of both physical[72] and psychological features,[73] and the manipulation of light and darkness, including tone contrast, sfumato (softening the transition between colours) and chiaroscuro (contrast between light and dark),[74] in a single unifying style[75] which expressed total compositional order, balance and harmony.

By far the most famous composer of church music in 16th-century Italy was Palestrina, the most prominent member of the Roman School, whose style of smooth, emotionally cool polyphony was to become the defining sound of the late 16th century, at least for generations of 19th- and 20th-century musicologists.

[81] Recent historians who take a more revisionist perspective, such as Charles Haskins (1860–1933), identify the hubris and nationalism of Italian politicians, thinkers, and writers as the cause of the distortion of the attitude towards the early modern period.

Haskins was one of the leading scholars in this school of thought, and it was his (along with several others) belief that the building blocks for the Italian Renaissance were all laid during the Middle Ages, calling on the rise of towns and bureaucratic states in the late 11th century as proof of the significance of this "pre-renaissance."

This period was eventually referred to as the "dark" ages in the 19th century by English historians, which has further tainted the narrative of medieval times in favour of promoting a positive feeling of individualism and humanism that spurred from the Renaissance.