Italian War of 1542–1546

Fighting began at once throughout the Low Countries; the following year saw the Franco-Ottoman alliance's attack on Nice, as well as a series of maneuvers in Northern Italy which culminated in the bloody Battle of Ceresole.

Henry, left alone but unwilling to return Boulogne to the French, continued to fight until 1546, when the Treaty of Ardres finally restored peace between France and England.

[2] Charles accepted, and was richly received; but while he was willing to discuss religious matters with his host—the Protestant Reformation being underway—he delayed on the question of political differences, and nothing had been decided by the time he left French territory.

[3] In March 1540, Charles proposed to settle the matter by having Maria of Spain marry Francis's younger son, the Duke of Orléans; the two would then inherit the Netherlands, Burgundy, and Charolais after the Emperor's death.

[13] The Imperial expedition, however, was entirely unsuccessful; storms scattered the invasion fleet soon after the initial landing, and Charles had returned to Spain with the remainder of his troops by November.

[14] On 8 March 1542, the new French ambassador, Antoine Escalin des Eymars, returned from Constantinople with promises of Ottoman aid in a war against Charles.

[19] Negotiations continued for weeks; finally, on 11 February 1543, Henry and Charles signed a treaty of offensive alliance, pledging to invade France within two years.

[18] Francis inexplicably halted with his army near Rheims; in the meantime, Charles attacked Wilhelm of Cleves, invading the Duchy of Jülich and capturing Düren.

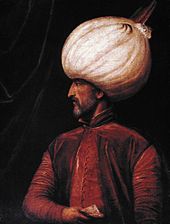

Barbarossa left the Dardanelles with more than a hundred galleys, raided his way up the Italian coast, and in July arrived in Marseilles, where he was welcomed by François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien, the commander of the French fleet.

[36] Although the French were victorious, the impending invasion of France itself by Charles and Henry forced Francis to recall much of his army from Piedmont, leaving Enghien without the troops he needed to take Milan.

[37] D'Avalos's victory over an Italian mercenary army in French service at the Battle of Serravalle in early June 1544 brought significant campaigning in Italy to an end.

Denmark-Norway, were to blockade The Sound and the Belt to Dutch shipping,[39][40] and a Danish contingent joined the Franco-Cleves army, which invaded Brabant in July.

[41] A peace treaty was signed, between Denmark-Norway and the Holy Roman Empire, in 1544 at Speyer; Charles acknowledged Christian III as king of Denmark and Norway and free passage through the Sound (Øresund) was ensured.

[39] On 31 December 1543, Henry and Charles had signed a treaty pledging to invade France in person by 20 June 1544; each was to provide an army of no less than 35,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry for the venture.

[44] On 15 May, Henry was informed by Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, that, after his raids, Scotland was no longer in a position to threaten him; he then began to make preparations for a personal campaign in France—against the advice of his council and the Emperor, who believed that his presence would be a hindrance.

By western continental standards, the army was obsolescent; it had little heavy cavalry and a shortage of both pike and shot, the bulk of its troops being armed with longbows or bills.

[52] While Henry continued to squabble with the Emperor over the goals of the campaign and his own presence in France, this massive army moved slowly and aimlessly into French territory.

Norfolk, ordered to besiege Ardres or Montreuil, advanced towards the latter; but he proved unable to mount an effective siege, complaining of inadequate supplies and poor organization.

[56] Charles himself, on the other hand, was still delayed at Saint-Dizier; the city, fortified by Girolamo Marini and defended by Louis IV de Bueil, Count of Sancerre, continued to hold out against the massive Imperial army.

[58] On 17 August, the French capitulated, and were permitted by the Emperor to leave the city with banners flying; their resistance for 41 days had broken the Imperial offensive.

[59] Some of Charles's advisers suggested withdrawing, but he was unwilling to lose face and continued to move towards Châlons, although the Imperial army was prevented from advancing across the Marne by a French force waiting at Jâlons.

[66] Charles, short on funds and needing to deal with increasing religious unrest in Germany, asked Henry to continue his invasion or to allow him to make a separate peace.

[67] By the time Henry had received the Emperor's letter, however, Charles had already concluded a treaty with Francis—the Peace of Crépy—which was signed by representatives of the monarchs at Crépy in Picardy on 18 September 1544.

[70] A second, secret accord was also signed; by its terms, Francis would assist Charles with reforming the church, with calling a General Council, and with suppressing Protestantism—by force if necessary.

[74] The two dukes quickly disobeyed this order and withdrew the bulk of the English army to Calais, leaving some 4,000 men to defend the captured city.

[77] Peace talks were attempted at Calais without result; Henry refused to consider returning Boulogne, and insisted that Francis abandon his support of the Scots.

[95] He was not, therefore, in a position to assist the German Protestants, who were now engaged in the Schmalkaldic War against the Emperor; by the time any French aid was to be forthcoming, Charles had already won his victory at the Battle of Mühlberg.

[98] Henry's successors continued his entanglements in Scotland; when, in 1548, friction with the Scots led to the resumption of hostilities around Boulogne, they decided to avoid a two-front war by returning the city four years early, in 1550.