Peloneustes

The long, narrow snout of Peloneustes could have been swung quickly through the water to catch fish, which it pierced with its numerous sharp teeth.

[2] Among these was the specimen which would become the holotype of Peloneustes philarchus, discovered by geologist Henry Porter in a clay pit close to Peterborough, England.

[6]: v–vi Naturalist Richard Lydekker was informed of a plesiosaur skeleton in the British Museum of Natural History by geologist George Charles Crick, who worked there.

The limb girdles had been heavily fragmented when the specimen arrived at the museum, but a worker named Lingard in the Geology Department managed to restore much of them.

After studying this and other specimens in the Leeds Collection, he concluded that plesiosaurs with shortened necks and large heads could not be classified as species of Plesiosaurus, meaning that "P." philarchus belonged to a different genus.

[11] In 1907, geologist Frédéric Jaccard published a description of two Peloneustes specimens from the Oxford Clay near Peterborough, housed in the Musée Paléontologique de Lausanne, Switzerland.

[12] In 1913, naturalist Hermann Linder described multiple specimens of Peloneustes philarchus housed in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen and State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Germany.

[19][17] In 1998, palaeontologist Frank Robin O'Keefe proposed that a pliosaurid specimen from the Lower Jurassic Posidonia Shale of Germany might represent a new species of Peloneustes.

[2][20] Palaeontologists Zulma Gasparini and Manuel A. Iturralde-Vinent assigned a pliosaurid from the Upper Jurassic Jagua Formation of Cuba to Peloneustes sp.

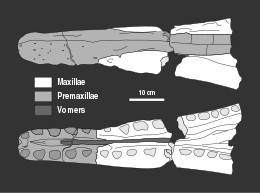

[23]: 3 While the holotype of Peloneustes lacks the rear portion of its cranium, many additional well-preserved specimens, including one that has not been crushed from top to bottom, have been assigned to this genus.

There has been some contention as to whether or not Peloneustes had lacrimals (bones bordering the lower front edges of the eye sockets), due to poor preservation.

[10]: 47, 52 However, in the same year, Linder reported 19 cervical, 5 pectoral, 20 dorsal, 2 sacral, and at least 17 caudal vertebrae in Peloneustes, based on a specimen in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen.

They bear strongly concave articular surfaces, with a prominent rim around the lower edge in the vertebrae located towards the front of the series.

[10]: 58, 62 Seeley initially described Peloneustes as a species of Plesiosaurus, a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for families).

[40] The bony labyrinth, a hollow within the skull which held a sensory organ associated with balance and orientation, of Peloneustes and other plesiosaurs is similar in shape to that of sea turtles.

However, Peloneustes appears to have been a predator of vertebrates, which contain less salt than invertebrates, therefore leading palaeontologist Leslie Noè to suggest in a 2001 dissertation that these glands would not have had to be especially large.

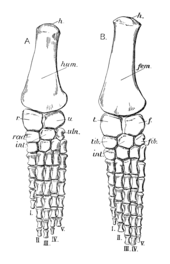

[43] A 2019 study by palaeontologist Corinna Fleischle and colleagues found that plesiosaurs had enlarged red blood cells, based on the morphology of their vascular canals, which would have aided them while diving.

In 2001, O'Keefe proposed that, much like falcons, pliosauromorph plesiosaurs such as Peloneustes probably were capable of moving quickly and nimbly, albeit inefficiently, to capture prey.

[24] Computer modelling by palaeontologist Susana Gutarra and colleagues in 2022 found that due to their large flippers, a plesiosaur would have produced more drag than a comparably-sized cetacean or ichthyosaur.

[45] Due to the reduction in drag by their shorter, deeper bodies, palaeontologist Judy Massare proposed in 1988 that plesiosaurs could actively search for and pursue their food instead of having to lie in wait for it.

To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like Peloneustes are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement.

The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding.

This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey.

The gracile snout's roughly circular cross-section would have minimised drag, while the long jaws were suited for quickly snapping up mobile prey.

The flat, enlarged palate and reinforced braincase of Peloneustes would have reduced the torsion, flexing, and shearing caused by the long snout.

While a skeleton, catalogued as NHMUK R3317, with belemnite remains in its stomach was assigned to Peloneustes by Andrews in 1910,[6]: xvi–xvii it is very incomplete and may actually belong to the contemporaneous pliosaurid Simolestes instead, as suggested by Noè.

These include the chondrichthyans Asteracanthus, Brachymylus, Heterodontus (or Paracestracion),[52] Hybodus, Ischyodus, Palaeobrachaelurus, Pachymylus, Protospinax, Leptacanthus, Notidanus, Orectoloboides, Spathobathis, and Sphenodus.

Actinopterygians were also present, represented by Aspidorhynchus, Asthenocormus, Caturus, Coccolepis, Heterostrophus, Hypsocormus, Leedsichthys, Lepidotes, Leptolepis, Mesturus, Osteorachis, Pachycormus, Pholidophorus, and Sauropsis.

[6]: viii [2] They were smaller plesiosaurs with thin teeth and long necks,[52] and, unlike pliosaurids such as Peloneustes, would have mainly eaten small animals.

[2] Besides Peloneustes, these pliosaurids include Liopleurodon ferox, Simolestes vorax, "Pliosaurus" andrewsi, Marmornectes candrewi,[57] Eardasaurus powelli, and, potentially, Pachycostasaurus dawni.