Thermoelectric effect

The thermoelectric effect is the direct conversion of temperature differences to electric voltage and vice versa via a thermocouple.

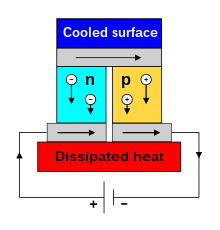

Conversely, when a voltage is applied to it, heat is transferred from one side to the other, creating a temperature difference.

Because the direction of heating and cooling is affected by the applied voltage, thermoelectric devices can be used as temperature controllers.

The Seebeck and Peltier effects are different manifestations of the same physical process; textbooks may refer to this process as the Peltier–Seebeck effect (the separation derives from the independent discoveries by French physicist Jean Charles Athanase Peltier and Baltic German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck).

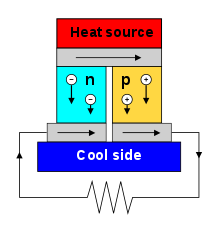

This is due to charge carrier particles having higher mean velocities (and thus kinetic energy) at higher temperatures, leading them to migrate on average towards the colder side, in the process carrying heat across the material.

Semiconductors of n-type and p-type are often combined in series as they have opposite directions for heat transport, as specified by the sign of their Seebeck coefficients.

[4] The Seebeck effect is the electromotive force (emf) that develops across two points of an electrically conducting material when there is a temperature difference between them.

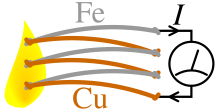

A thermocouple measures the difference in potential across a hot and cold end for two dissimilar materials.

First discovered in 1794 by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta,[5][note 1] it is named after the Russian born, Baltic German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck who rediscovered it in 1821.

Seebeck observed what he called "thermomagnetic effect" wherein a magnetic compass needle would be deflected by a closed loop formed by two different metals joined in two places, with an applied temperature difference between the joints.

Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted noted that the temperature difference was in fact driving an electric current, with the generation of magnetic field being an indirect consequence, and so coined the more accurate term "thermoelectricity".

The Seebeck coefficients generally vary as function of temperature and depend strongly on the composition of the conductor.

In practice, thermoelectric effects are essentially unobservable for a localized hot or cold spot in a single homogeneous conducting material, since the overall EMFs from the increasing and decreasing temperature gradients will perfectly cancel out.

Thermocouples involve two wires, each of a different material, that are electrically joined in a region of unknown temperature.

This direct relationship allows the thermocouple arrangement to be used as a straightforward uncalibrated thermometer, provided knowledge of the difference in

They are optimized differently from thermocouples, using high quality thermoelectric materials in a thermopile arrangement, to maximize the extracted power.

This is known as the Peltier effect: the presence of heating or cooling at an electrified junction of two different conductors.

The effect is named after French physicist Jean Charles Athanase Peltier, who discovered it in 1834.

A typical Peltier heat pump involves multiple junctions in series, through which a current is driven.

Notably, the Peltier thermoelectric cooler is a refrigerator that is compact and has no circulating fluid or moving parts.

This rapid reversing heating and cooling effect is used by many modern thermal cyclers, laboratory devices used to amplify DNA by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

is passed through a homogeneous conductor, the Thomson effect predicts a heat production rate per unit volume.

The Thomson effect is a manifestation of the direction of flow of electrical carriers with respect to a temperature gradient within a conductor.

As stated above, the Seebeck effect generates an electromotive force, leading to the current equation[11]

If temperature and charge change with time, the full thermoelectric equation for the energy accumulation,

If the material is not in a steady state, a complete description needs to include dynamic effects such as relating to electrical capacitance, inductance and heat capacity.

The junction region is an inhomogeneous body, assumed to be stable, not suffering amalgamation by diffusion of matter.

But in the case of continuous variation in the media, heat transfer and thermodynamic work cannot be uniquely distinguished.

This is more complicated than the often considered thermodynamic processes, in which just two respectively homogeneous subsystems are connected.

It was not satisfactorily proven until the advent of the Onsager relations, and it is worth noting that this second Thomson relation is only guaranteed for a time-reversal symmetric material; if the material is placed in a magnetic field or is itself magnetically ordered (ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, etc.