Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The 47th Congress passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act during its lame duck session and President Chester A. Arthur, himself a former spoilsman, signed the bill into law.

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act provided for the selection of some government employees by competitive exams, rather than ties to politicians or political affiliation.

It also made it illegal to fire or demote these government officials for political reasons and created the United States Civil Service Commission to enforce the merit system.

[2] After taking office in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes established a special cabinet committee charged with drawing up new rules for federal appointments.

[3] Hayes's efforts for reform brought him into conflict with the Stalwart, or pro-spoils, branch of the Republican party, led by Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York.

[5] According to historian Eric Foner, the advocacy of civil service reform was recognized by blacks as an effort that would stifle their economic mobility and prevent "the whole colored population" from holding public office.

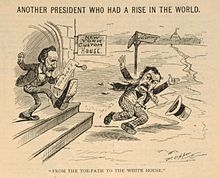

[6] Chester Arthur, Collector of the Port of New York, and his partisan subordinates Alonzo B. Cornell and George H. Sharpe, all Conkling supporters, obstinately refused to obey the president's order.

[15] In 1880, Democratic Senator George H. Pendleton of Ohio introduced legislation to require the selection of civil servants based on merit as determined by an examination, but the measure failed to pass.

Hayes did not seek a second term as president, and was succeeded by fellow Republican James A. Garfield, who won the 1880 presidential election on a ticket with former Port Collector Chester A. Arthur.

[23] The party's disastrous performance in the 1882 elections helped convince many Republicans to support the civil service reform during the 1882 lame-duck session of Congress.

[25] To the surprise of his critics, Arthur acted quickly to appoint the members of the newly created Civil Service Commission, naming reformers Dorman Bridgman Eaton, John Milton Gregory, and Leroy D. Thoman as commissioners.

As long as candidates passed the newly created exams, the bureau and division chiefs were left with free reign to appoint whomever they wished to the positions.

The Civil Service Commission was abolished and its functions were replaced by the Office of Personnel Management, the Merit Systems Protection Board, and the Federal Labor Relations Authority.

As a result of this settlement agreement, PACE, the main entry-level test for candidates seeking positions in the federal government’s executive branch, was scrapped.