Pendulum (mechanics)

A pendulum is a body suspended from a fixed support such that it freely swings back and forth under the influence of gravity.

When released, the restoring force acting on the pendulum's mass causes it to oscillate about the equilibrium position, swinging it back and forth.

Simplifying assumptions can be made, which in the case of a simple pendulum allow the equations of motion to be solved analytically for small-angle oscillations.

Since in the model there is no frictional energy loss, when given an initial displacement it swings back and forth with a constant amplitude.

The model is based on the assumptions: The differential equation which governs the motion of a simple pendulum is where g is the magnitude of the gravitational field, ℓ is the length of the rod or cord, and θ is the angle from the vertical to the pendulum.

This is because only changes in speed are of concern and the bob is forced to stay in a circular path.

The short violet arrow represents the component of the gravitational force in the tangential axis, and trigonometry can be used to determine its magnitude.

The negative sign on the right hand side implies that θ and a always point in opposite directions.

This makes sense because when a pendulum swings further to the left, it is expected to accelerate back toward the right.

First start by defining the torque on the pendulum bob using the force due to gravity.

It can also be obtained via the conservation of mechanical energy principle: any object falling a vertical distance

If the pendulum starts its swing from some initial angle θ0, then y0, the vertical distance from the screw, is given by

If the origin of the Cartesian coordinate system is defined as the point of suspension (or simply pivot), then the bob is at

The differential equation given above is not easily solved, and there is no solution that can be written in terms of elementary functions.

However, adding a restriction to the size of the oscillation's amplitude gives a form whose solution can be easily obtained.

The error due to the approximation is of order θ3 (from the Taylor expansion for sin θ).

Note that under the small-angle approximation, the period is independent of the amplitude θ0; this is the property of isochronism that Galileo discovered.

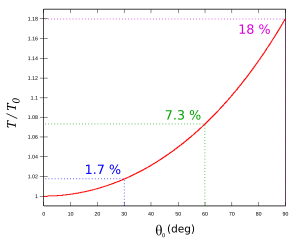

For amplitudes beyond the small angle approximation, one can compute the exact period by first inverting the equation for the angular velocity obtained from the energy method (Eq.

(Conversely, a pendulum close to its maximum can take an arbitrarily long time to fall down.)

For comparison of the approximation to the full solution, consider the period of a pendulum of length 1 m on Earth (g = 9.80665 m/s2) at an initial angle of 10 degrees is

denotes the double factorial, an exact solution to the period of a simple pendulum is:

, this is often avoided in applications because it is not possible to express this integral in a closed form in terms of elementary functions.

This has made way for research on simple approximate formulae for the increase of the pendulum period with amplitude (useful in introductory physics labs, classical mechanics, electromagnetism, acoustics, electronics, superconductivity, etc.

[12] As accurate timers and sensors are currently available even in introductory physics labs, the experimental errors found in ‘very large-angle’ experiments are already small enough for a comparison with the exact period, and a very good agreement between theory and experiments in which friction is negligible has been found.

Since this activity has been encouraged by many instructors, a simple approximate formula for the pendulum period valid for all possible amplitudes, to which experimental data could be compared, was sought.

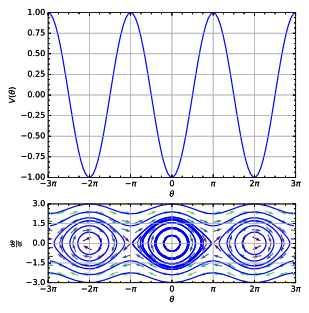

With a large enough initial velocity the pendulum does not oscillate back and forth but rotates completely around the pivot.

Notice these formulae can be particularized into the two previous cases studied before just by considering the mass of the rod or the bob to be zero respectively.

Notice how similar it is to the angular frequency in a spring-mass system with effective mass.

where the damping is assumed to be directly proportional to the angular velocity (this is true for low-speed air resistance, see also Drag (physics)).

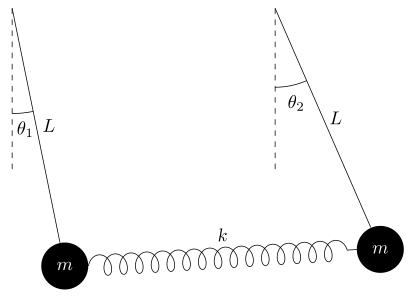

The equations of motion for two identical simple pendulums coupled by a spring connecting the bobs can be obtained using Lagrangian mechanics.