Lagrangian mechanics

It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange in his presentation to the Turin Academy of Science in 1760[1] culminating in his 1788 grand opus, Mécanique analytique.

[7] Lagrangian mechanics adopts energy rather than force as its basic ingredient,[5] leading to more abstract equations capable of tackling more complex problems.

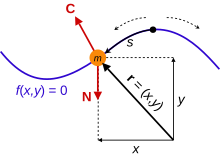

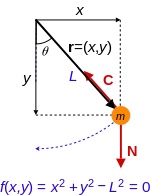

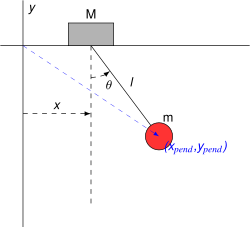

[7] For a wide variety of physical systems, if the size and shape of a massive object are negligible, it is a useful simplification to treat it as a point particle.

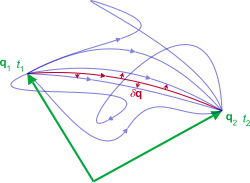

The constraint equations determine the allowed paths the particles can move along, but not where they are or how fast they go at every instant of time.

In a set of curvilinear coordinates ξ = (ξ1, ξ2, ξ3), the law in tensor index notation is the "Lagrangian form"[18][19]

where Fa is the a-th contravariant component of the resultant force acting on the particle, Γabc are the Christoffel symbols of the second kind,

is the kinetic energy of the particle, and gbc the covariant components of the metric tensor of the curvilinear coordinate system.

Mathematically, the solutions of the differential equation are geodesics, the curves of extremal length between two points in space (these may end up being minimal, that is the shortest paths, but not necessarily).

With appropriate extensions of the quantities given here in flat 3D space to 4D curved spacetime, the above form of Newton's law also carries over to Einstein's general relativity, in which case free particles follow geodesics in curved spacetime that are no longer "straight lines" in the ordinary sense.

They are not the same as the actual displacements in the system, which are caused by the resultant constraint and non-constraint forces acting on the particle to accelerate and move it.

Recalling the Lagrange form of Newton's second law, the partial derivatives of the kinetic energy with respect to the generalized coordinates and velocities can be found to give the desired result:[9]

[34] Historically, the idea of finding the shortest path a particle can follow subject to a force motivated the first applications of the calculus of variations to mechanical problems, such as the Brachistochrone problem solved by Jean Bernoulli in 1696, as well as Leibniz, Daniel Bernoulli, L'Hôpital around the same time, and Newton the following year.

[35] These ideas in turn lead to the variational principles of mechanics, of Fermat, Maupertuis, Euler, Hamilton, and others.

Hamilton's principle is still valid even if the coordinates L is expressed in are not independent, here rk, but the constraints are still assumed to be holonomic.

For the case of a conservative force given by the gradient of some potential energy V, a function of the rk coordinates only, substituting the Lagrangian L = T − V gives

and by the chain rule for partial differentiation, Lagrange's equations are invariant under this transformation;[41][citation needed]

If the potential energy is a homogeneous function of the coordinates and independent of time,[43] and all position vectors are scaled by the same nonzero constant α, rk′ = αrk, so that

Since the lengths and times have been scaled, the trajectories of the particles in the system follow geometrically similar paths differing in size.

A particle of mass m moves under the influence of a conservative force derived from the gradient ∇ of a scalar potential,

These equations may look quite complicated, but finding them with Newton's laws would have required carefully identifying all forces, which would have been much more laborious and prone to errors.

Since the relative motion only depends on the magnitude of the separation, it is ideal to use polar coordinates (r, θ) and take r = |r|,

This viewpoint, that fictitious forces originate in the choice of coordinates, often is expressed by users of the Lagrangian method.

This view arises naturally in the Lagrangian approach, because the frame of reference is (possibly unconsciously) selected by the choice of coordinates.

[51] Dissipation (i.e. non-conservative systems) can also be treated with an effective Lagrangian formulated by a certain doubling of the degrees of freedom.

The ideas in Lagrangian mechanics have numerous applications in other areas of physics, and can adopt generalized results from the calculus of variations.

However, from the physical point-of-view there is an obstacle to include time derivatives higher than the first order, which is implied by Ostrogradsky's construction of a canonical formalism for nondegenerate higher derivative Lagrangians, see Ostrogradsky instability Lagrangian mechanics can be applied to geometrical optics, by applying variational principles to rays of light in a medium, and solving the EL equations gives the equations of the paths the light rays follow.

Some features of Lagrangian mechanics are retained in the relativistic theories but difficulties quickly appear in other respects.

In particular, the EL equations take the same form, and the connection between cyclic coordinates and conserved momenta still applies, however the Lagrangian must be modified and is not simply the kinetic minus the potential energy of a particle.

In 1948, Feynman discovered the path integral formulation extending the principle of least action to quantum mechanics for electrons and photons.

In Lagrangian mechanics, the generalized coordinates form a discrete set of variables that define the configuration of a system.