Pepi I Meryre

At the same time, Pepi favored the rise of small provincial centres and recruited officials of non-noble extraction to curtail the influence of powerful local families.

Trade with Byblos, Ebla and the oases of the Western Desert flourished, while Pepi launched mining and quarrying expeditions to Sinai and further afield.

[35] A final unnamed consort, only referred to by her title "Weret-Yamtes"[36] meaning "great of affection",[37] is known from inscriptions uncovered in the tomb of Weni, an official serving Pepi.

Othoês, Phius (in Greek, φιός), and Methusuphis are understood to be the Hellenized forms for Teti, Pepi I and Merenre, respectively,[52][note 7] meaning that the Aegyptiaca omits Userkare.

[72] As further evidence of the importance of this event in Pepi's case, the state administration seems to have had a tendency to mention his first jubilee repeatedly in the years following its celebration until the end of his rule in connection with building activities.

For example, Pepi's final 25th cattle count reported on the Sixth Dynasty royal annals is associated with his first Sed festival even though it probably had taken place some 19 years prior.

[8][52] The Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati has argued in support of Manetho's claim, noting for example that Teti's reign saw a significant increase in the number of guards at the Egyptian court, who became responsible for the everyday care of the king.

[74] Rather, Userkare could have been an usurper[note 12] and a descendant of a lateral branch of the Fifth Dynasty royal family who seized power briefly in a coup,[81] possibly with the support of the priesthood of the sun god Ra.

Further archeological evidence of Userkare's illegitimacy in the eyes of his successor is the absence of any mention of him in the tombs and biographies of the many Egyptian officials who served under both Teti and Pepi I.

[89] At the same time as he apparently distanced himself from his father's line, Pepi transformed his mother's tomb into a pyramid and posthumously bestowed a new title on her, "Daughter of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt", thereby emphasising his royal lineage as a descendant of Unas, last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty.

[95] The Sixth Dynasty royal annals, only a small part of which are still legible, record further activities during Pepi's reign, including the offering of milk and young cows for a feast of Ra, the building of a "south chapel" on the occasion of the new year and the arrival of messengers at court.

[113][114] The political importance of these marriages[114] is furthered by the fact that for the first and last time until the 26th Dynasty some 1800 years later, a woman, Khui's wife Nebet, bore the title of vizier of Upper Egypt.

[39] The Coptos Decrees, which record successive pharaohs granting tax exemptions to the temple, as well as official honours bestowed by the kings on the local ruling family while the Old Kingdom society was collapsing, manifest this.

[148] The reign of Pepi I marks the apogee of the Sixth Dynasty foreign policy, with flourishing trade, several mining and quarrying expeditions and major military campaigns.

[153][note 25] The high official, Iny, served Pepi during several successful expeditions to Byblos for which the king rewarded him with the name "Inydjefaw", meaning, "He who brings back provisions".

[171] At the same time, an extensive network of caravan routes traversed Egypt's Western Desert, for example, from Abydos to the Kharga Oasis and from there to the Dakhla and Selima Oases.

Whether they were the result of religious or political motives, exemptions created precedents that encouraged other institutions to request similar treatment, weakening the power of the state as they accumulated over time.

[177] Further domestic activities related to agriculture and the economy may be inferred from the inscriptions found in the tomb of Nekhebu, a high official belonging to the family of Senedjemib Inti, a vizier during the late Fifth Dynasty.

[178][179] Pepi I built extensively throughout Egypt,[181] so much so that in 1900 the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie stated "this king has left more monuments, large and small, than any other ruler before the Twelfth Dynasty".

He sees Pepi's rule as marking the apogee of the Old Kingdom owing to the flurry of building activities, administrative reforms, trade and military campaigns at the time.

[197] For the Egyptologist Juan Moreno García, this proximity demonstrates the direct power that the king still held over the temples' economic activities and internal affairs during the Sixth Dynasty.

[116] An alabaster statue of an ape with its offspring bearing Pepi I's cartouche[214] was uncovered in the same location, but it was probably a gift of the king to a high official who then dedicated it to Satet.

[219] For the Egyptologist David Warburton, the reigns of Pepi I and II mark the first period during which small stone temples dedicated to local deities were built in Egypt.

[223][242] Their function, like that of all funerary literature, was to enable the reunion of the ruler's ba and Ka, leading to the transformation into an akh,[243][244] and to secure eternal life among the gods in the sky.

[223] Both the temple and the causeway are now heavily damaged due the activity of lime makers, who extracted and burned the construction stones to turn them into mortar and whitewash in later times.

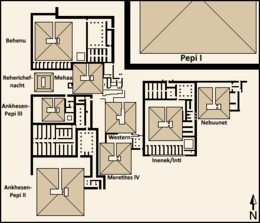

The name, image and titles of this queen are inscribed on jambs and two 2.2 m (7.2 ft) high red-painted obelisks on either side of the gateway to the mortuary temple, establishing that Inenek-Inti was buried there.

[260][261][262] Substantial remains of funerary equipment were found inside including wooden weights, ostrich feathers, copper fish hooks, and fired-clay vessels,[260] but none bore their owner's name.

Painted reliefs of which only scant remains have been found including a small scene depicting the queen and a princess on a boat among papyrus plants, adorned the accompanying funerary temple.

[261][262] Directly adjacent to Mehaa's pyramid's eastern face was her mortuary temple, where a relief bearing the name and image of Prince Hornetjerykhet, her son, was uncovered.

[281] The stone quarrying activities, which were limited to Pepi's necropolis during the New Kingdom and had spared his mortuary temple, became widespread during the Late Period of Egypt, with intermittent burials continuing nonetheless.