Perfume

Perfume (UK: /ˈpɜːfjuːm/, US: /pərˈfjuːm/ ⓘ) is a mixture of fragrant essential oils or aroma compounds (fragrances), fixatives and solvents, usually in liquid form, used to give the human body, animals, food, objects, and living-spaces an agreeable scent.

Modern perfumery began in the late 19th century with the commercial synthesis of aroma compounds such as vanillin or coumarin, which allowed for the composition of perfumes with smells previously unattainable solely from natural aromatics.

[citation needed] One of the world's first-recorded chemists is considered to be a woman named Tapputi, a perfume maker mentioned in a cuneiform tablet from the 2nd millennium BC in Mesopotamia.

They were discovered in an ancient perfumery, a 300-square-meter (3,230 sq ft) factory[8] housing at least 60 stills, mixing bowls, funnels, and perfume bottles.

[9] In May 2018, an ancient perfume "Rodo" (Rose) was recreated for the Greek National Archaeological Museum's anniversary show "Countless Aspects of Beauty", allowing visitors to approach antiquity through their olfaction receptors.

A temple to Athena in Elis, near Olympia, was said to have saffron blended into its wall plaster, allowing the interior to remain fragrant for 500 years.

[11] In the 9th century the Arab chemist Al-Kindi (Alkindus) wrote the Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations, which contained more than a hundred recipes for fragrant oils, salves, aromatic waters, and substitutes or imitations of costly drugs.

The Persian chemist Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna) introduced the process of extracting oils from flowers by means of distillation, the procedure most commonly used today.

[19][20][21] The art of perfumery prospered in Renaissance Italy, and in the 16th century the personal perfumer to Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589), René the Florentine (Renato il fiorentino), took Italian refinements to France.

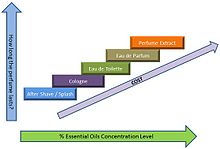

In some cases, words such as extrême, intense, or concentrée that might indicate a higher aromatic concentration are actually completely different fragrances, related only because of a similar perfume accord.

This complexity adds a layer of nuance to the understanding and appreciation of perfumery, where variations in concentration and formulation can significantly alter the olfactory ("the sense of smell") experience.

The term "cologne" was first used in Europe in the 18th century to refer to a family of fresh, citrus-based fragrances distilled using extracts from citrus, floral, and woody ingredients.

As this process accelerated, perfume houses borrowed the term "cologne" to refer to an even more diluted interpretation of their fragrances than eau de toilette.

Many modern perfumes are never offered in extrait or eau de cologne formulations, and EdP and EdT account for the vast majority of new launches.

[30] The modern perfume industry encourages the practice of layering fragrance so that it is released in different intensities depending upon the time of the day.

Lightly scented products such as bath oil, shower gel, and body lotion are recommended for the morning; eau de toilette is suggested for the afternoon; and perfume applied to the pulse points for evening.

Even if they were widely published, they would be dominated by such complex ingredients and odorants that they would be of little use in providing a guide to the general consumer in description of the experience of a scent.

[39] The five main families are Floral, Oriental, Woody, Aromatic Fougère, and Fresh, the first four from the classic terminology and the last from the modern oceanic category.

For instance, Calone, a compound of synthetic origin, imparts a fresh ozonous metallic marine scent that is widely used in contemporary perfumes.

This is due to the use of heat, harsh solvents, or through exposure to oxygen in the extraction process which will denature the aromatic compounds, which either change their odor character or renders them odorless.

"[48] Antique or badly preserved perfumes undergoing this analysis can also be difficult due to the numerous degradation by-products and impurities that may have resulted from breakdown of the odorous compounds.

The French Supreme Court has twice taken the position that perfumes lack the creativity to constitute copyrightable expressions (Bsiri-Barbir v. Haarman & Reimer, 2006; Beaute Prestige International v. Senteur Mazal, 2008).

As well, the furanocoumarin present in natural extracts of grapefruit or celery can cause severe allergic reactions and increase sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation.

[citation needed] A number of national and international surveys have identified balsam of Peru, often used in perfumes, as being in the "top five" allergens most commonly causing patch test reactions in people referred to dermatology clinics.

These reports were evaluated by the EU Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety (SCCS, formerly the SCCNFP[65]) and musk xylene was found to be safe for continued use in cosmetic products.

[76] Synthetic musks are pleasant in smell and relatively inexpensive, as such they are often employed in large quantities to cover the unpleasant scent of laundry detergents and many personal cleaning products.

Due to their large-scale use, several types of synthetic musks have been found in human fat and milk,[77] as well as in the sediments and waters of the Great Lakes.

[citation needed] Fragrance compounds in perfumes will degrade or break down if improperly stored in the presence of heat, light, oxygen, and extraneous organic materials.

Sprays also have the advantage of isolating fragrance inside a bottle and preventing it from mixing with dust, skin, and detritus, which would degrade and alter the quality of a perfume.

All scents in their collection are preserved in non-actinic glass flasks flushed with argon gas, stored in thermally insulated compartments maintained at 12 °C (54 °F) in a large vault.