Perm (hairstyle)

Each time the tongs were applied, they were moved slightly in a direction normal to the lock of hair, thus producing a continuous flat or two-dimensional wave.

However, in spite of its drawbacks, forms of Marcel waving have persisted until today, when speedy results and low cost are important.

This was not only a political gesture but a practical one, as women began to take over men's work due to the great shortage of labour during the First World War.

An early alternative method for curling hair that was suitable for use on people was invented in 1905 by German hairdresser Karl Nessler.

Previously, wigs had been set with caustic chemicals to form curls, but these recipes were too harsh to use next to human skin.

These hot rollers were kept from touching the scalp by a complex system of countering weights which were suspended from an overhead chandelier and mounted on a stand.

Nessler opened a shop on East 49th Street, and soon had salons in Chicago, Detroit, Palm Beach, Florida and Philadelphia.

However, his machine made little impression in Europe and his first attempts were not even mentioned in the professional press, perhaps because they were too long-winded, cumbersome and dangerous.

He became aware of the possibilities of electrical permanent waving particularly when shorter hair allowed the design of smaller equipment.

Isidoro Calvete was a Spanish immigrant who set up a workshop for the repair and manufacture of electrical equipment in the same area of London in 1917.

Suter consulted him on the heater and Calvete designed a practical model consisting of two windings inserted into an aluminium tube.

Suter patented the design in his own name and for the next 12 years ordered all his hairdressing equipment from Calvete but marketed under his commercial name, Eugene Ltd, which became synonymous with permanent waving throughout the world.

[6] Its products included colour rinses, lustre-lending shampoos, setting lotions and patented steaming sachets as well as its curlers and electric dryer.

'Oh, a Eugène wave, please!’From the onset, Eugene had realised the importance of the United States market and made great inroads, challenging Nessler who had started up there.

Considerable ingenuity was exercised in designing the curler to minimize the time, effort and difficulties entailed in winding.

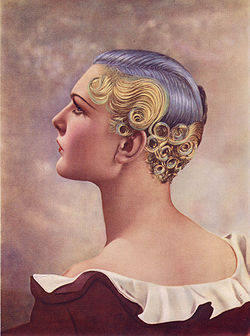

In early models, the heaters had a tendency to flop downward on to the head, but with improved designs, they tended to point outwards (see illustration).

Mayer attempted to claim a patent on this method of winding, which was challenged in a Federal lawsuit by the National Hairdressers' and Cosmetologists' Association.

The trend was to replace some of the tubular heaters on the sides of the head with croquignole ones, to allow greater scope of styling.

The bottom of the pipe was mounted on a base with wheels which enabled the device to be moved easily between clients or to one side of the salon.

Although heat was required for perming, it was soon realized that if an improvement had to be made over the Marcel method, other means were necessary to avoid overheating and to speed up the waving process.

In chemistry, this is the opposite of oxidation and can mean the removal of oxygen or, in this case, the addition of hydrogen, which by breaking the bonds of the keratin in the hair, allowed waving to take place more easily.

This resulted in addition of a sulfite, bisulfite or metabisulfite to Icall reagents, sulfur dioxide, a reducing agent, being evolved on heating.

Meanwhile, hairdressers sought to improve the process and reduce the work involved; this meant savings at the lower end of the market and yet more women getting their hair permed.

This resulted in many copies of the original equipment being made by reputable firms in some cases with innovations of their own: The manner in which reagents worked when applied to the hair and heated, was not only due to the chemicals they contained, but also the effect of the water.

A further advance was the use of so-called sachets: small absorbent pads containing certain chemicals, attached to foil or other waterproof material, such as vegetable parchment.

Their method used bi-sulfide solution and was often applied at the salon, left on while the client went home and removed the next day, leading it to be called the overnight wave.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, all production of such equipment stopped in Europe and hardly recovered afterwards, being replaced either by home heater kits or cold-waving methods.

This chemical breaks open the disulfide linkages between the polypeptide bonds in the keratin; the protein structure in the hair.

The process was patented and invented by a Japanese company, Paimore Ltd.[13] There are two parts to a perm: the physical action of wrapping the hair, and the chemical phase.

Glyceryl monothioglycolate is considered a recent innovation in perming technology due to its high curling power near the pH of hair.