Permanent income hypothesis

The permanent income hypothesis (PIH) is a model in the field of economics to explain the formation of consumption patterns.

Originally applied to consumption and income, the process of future expectations is thought to influence other phenomena.

The formation of consumption patterns opposite to predictions was an outstanding problem faced by the Keynesian orthodoxy.

[2][3] In its post-war synthesis, the Keynesian perspective was responsible for pioneering many innovations in recession management, economic history, and macroeconomics.

Like the neoclassical school that preceded it, early inconsistencies had their roots in socio-political events contrary to the predictions put forward.

[2][3] The introduction of the absolute income hypothesis is often attributed to John Maynard Keynes, a British economist, who wrote several books which are now the basis for Keynesian economics.

However, inconsistencies were not resolved swiftly, and economists were unable to explain the consistency of the savings rate in the face of rising real incomes (Fig.

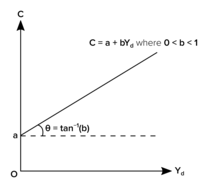

His MPC and MPS spending multipliers developed into the absolute income hypothesis (1), and were influential to the government responses to the ensuing depression.

[3][6] The American economist Milton Friedman developed the permanent income hypothesis in his 1957 book A Theory of the Consumption Function.

[7][8] Friedman explains this by how, for example, consumers would consistently save more when they expect their long-term income to increase.

If the latter definition is adopted, as seems highly desirable in applying the hypothesis to empirical data—though unfortunately I have been able to do so to only a limited extent—much that one classifies offhand as consumption is reclassified as savings.

'In his theory, John Maynard Keynes supported economic policy makers by his argument emphasizing their capability of macroeconomic fine tuning.

It must be stressed that the relation characterized by substantial stability links current consumption expenditures to current disposable income—and, on these grounds, a considerable leeway is provided for aggregate demand stimulation, since a change in income immediately results in a multiplied shift in aggregate demand (this is the essence of the Keynesian case of the multiplier effect).

According to the basic theory of Keynes, governments are always capable of countercyclical fine tuning of macroeconomic systems through demand management,[14] although Friedman disputes this, arguing in a 1961 journal article that Keynesian macroeconomic fine tuning will succumb to 'long and variable lags.

[19] According to the PIH, the distribution of consumption across consecutive periods is the result of an optimizing method by which each consumer tries to maximize his utility.

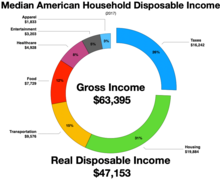

) by differentiating between transitory and permanent income (which was also taken to include ordinal elements like human capital and talents).

In an earlier study, Friedman, Kuznets (1945), he proposes the idea of transitory and permanent income.

[7] Consider a (potentially infinitely lived) consumer who maximizes his expected lifetime utility from the consumption of a stream of goods

, the optimal consumption choice of the consumer is governed by the Euler equation Given a finite time horizon of length

Solving the consumer's budget constraint forward to the last period, we determine the consumption function is given by Over an infinite time horizon, we instead impose a no Ponzi game condition, which prevents the consumer from continuously borrowing and rolling over their debt to future periods, by requiring The resulting consumption function is then Both expressions (2) and (3) capture the essence of the permanent income hypothesis: current consumption is determined by a combination of current non human wealth

[22] Some have attempted to improve Friedman's original hypothesis by including liquidity constraints, most notably Christopher D.

[24] An early test of the permanent income hypothesis was reported by Robert Hall in 1978, and, assuming rational expectations, finds consumption follows a martingale sequence.

[30] The evidence finds that consumption is sensitive to the income refund, with a marginal propensity to consume between 35 and 60%.

Stephens (2003) finds the consumption patterns of social security recipients in the United States is not well explained by the permanent income hypothesis.

It argues that rejections of the hypothesis are based on publication bias[33] and that after correction, it is consistent with data.

[34] According to Costas Meghir, unresolved inconsistencies explain the failure of transitory Keynesian demand management techniques to achieve its policy targets.

[2] In a simple Keynesian framework the marginal propensity to consume (MPC)[η] is assumed constant, and so temporary tax cuts can have a large stimulating effect on demand.

[37] Friedman received the 1976 Sveriges Riksbank prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 'For his achievements in the field of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.

'[38] The 'consumption analysis' has been interpreted by Worek (2010) as representing Friedman's contributions in the form of the permanent income hypothesis,[38] while the monetary history and stabilization section has been interpreted to refer to his work on monetary policy and history, and monetarism, which seeks to stabilize a currency, preventing erratic swings, respectively.

[38][39] The Permanent Income Hypothesis has been met with praise from Austrian economists, such as Robert Mulligan.