Permittivity

Another common term encountered for both absolute and relative permittivity is the dielectric constant which has been deprecated in physics and engineering[3] as well as in chemistry.

Its relation to permittivity in the very simple case of linear, homogeneous, isotropic materials with "instantaneous" response to changes in electric field is:

In general, permittivity is not a constant, as it can vary with the position in the medium, the frequency of the field applied, humidity, temperature, and other parameters.

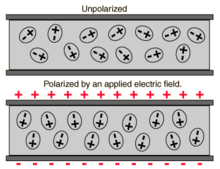

The susceptibility is defined as the constant of proportionality (which may be a tensor) relating an electric field E to the induced dielectric polarization density P such that

The capacitance of a capacitor is based on its design and architecture, meaning it will not change with charging and discharging.

If the Gaussian surface uniformly encloses an insulated, symmetrical charge arrangement, the formula can be simplified to

That is, the polarization is a convolution of the electric field at previous times with time-dependent susceptibility given by χ(Δt).

It is convenient to take the Fourier transform with respect to time and write this relationship as a function of frequency.

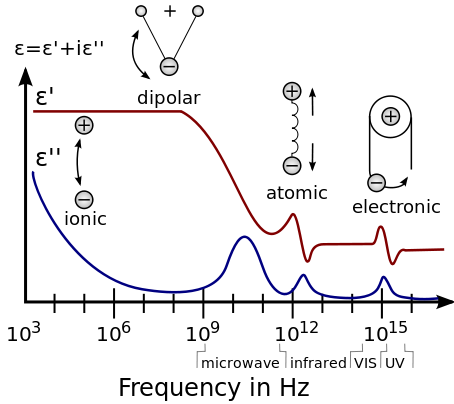

This frequency dependence reflects the fact that a material's polarization does not change instantaneously when an electric field is applied.

For this reason, permittivity is often treated as a complex function of the (angular) frequency ω of the applied field:

At the high-frequency limit (meaning optical frequencies), the complex permittivity is commonly referred to as ε∞ (or sometimes εopt[11]).

At the plasma frequency and below, dielectrics behave as ideal metals, with electron gas behavior.

Since the response of materials to alternating fields is characterized by a complex permittivity, it is natural to separate its real and imaginary parts, which is done by convention in the following way:

The signs used here correspond to those commonly used in physics, whereas for the engineering convention one should reverse all imaginary quantities.

The dielectric function ε(ω) must have poles only for frequencies with positive imaginary parts, and therefore satisfies the Kramers–Kronig relations.

However, in the narrow frequency ranges that are often studied in practice, the permittivity can be approximated as frequency-independent or by model functions.

At a given frequency, the imaginary part, ε″, leads to absorption loss if it is positive (in the above sign convention) and gain if it is negative.

In the case of solids, the complex dielectric function is intimately connected to band structure.

The primary quantity that characterizes the electronic structure of any crystalline material is the probability of photon absorption, which is directly related to the imaginary part of the optical dielectric function ε(ω).

In this expression, Wc,v(E) represents the product of the Brillouin zone-averaged transition probability at the energy E with the joint density of states,[13][14] Jc,v(E); φ is a broadening function, representing the role of scattering in smearing out the energy levels.

According to the Drude model of magnetized plasma, a more general expression which takes into account the interaction of the carriers with an alternating electric field at millimeter and microwave frequencies in an axially magnetized semiconductor requires the expression of the permittivity as a non-diagonal tensor:[18]

Materials can be classified according to their complex-valued permittivity ε, upon comparison of its real ε′ and imaginary ε″ components (or, equivalently, conductivity, σ, when accounted for in the latter).

is associated with a good conductor; such materials with non-negligible conductivity yield a large amount of loss that inhibit the propagation of electromagnetic waves, thus are also said to be lossy media.

At moderate frequencies, the energy is too high to cause rotation, yet too low to affect electrons directly, and is absorbed in the form of resonant molecular vibrations.

In water, this is where the absorptive index starts to drop sharply, and the minimum of the imaginary permittivity is at the frequency of blue light (optical regime).

While carrying out a complete ab initio (that is, first-principles) modelling is now computationally possible, it has not been widely applied yet.

The complex permittivity is evaluated over a wide range of frequencies by using different variants of dielectric spectroscopy, covering nearly 21 orders of magnitude from 10−6 to 1015 hertz.

In order to study systems for such diverse excitation fields, a number of measurement setups are used, each adequate for a special frequency range.

Various microwave measurement techniques are outlined in Chen et al.[22] Typical errors for the Hakki–Coleman method employing a puck of material between conducting planes are about 0.3%.

Dual polarisation interferometry is also used to measure the complex refractive index for very thin films at optical frequencies.