Perpetual motion

A common example is devices powered by ocean currents, whose energy is ultimately derived from the Sun, which itself will eventually burn out.

[13] For millennia, it was not clear whether perpetual motion devices were possible or not, until the development of modern theories of thermodynamics showed that they were impossible.

By way of example, clocks and other low-power machines, such as Cox's timepiece, have been designed to run on the differences in barometric pressure or temperature between night and day.

Noether's theorem, which was proven mathematically in 1915, states that any conservation law can be derived from a corresponding continuous symmetry of the action of a physical system.

[24] The principles of thermodynamics are so well established, both theoretically and experimentally, that proposals for perpetual motion machines are universally dismissed by physicists.

The difficulty (and the value) of such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones tend to arise from physicists' own thought experiments and often shed light upon certain aspects of physics.

So, for example, the thought experiment of a Brownian ratchet as a perpetual motion machine was first discussed by Gabriel Lippmann in 1900 but it was not until 1912 that Marian Smoluchowski gave an adequate explanation for why it cannot work.

But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.In the mid-19th-century Henry Dircks investigated the history of perpetual motion experiments, writing a vitriolic attack on those who continued to attempt what he believed to be impossible: There is something lamentable, degrading, and almost insane in pursuing the visionary schemes of past ages with dogged determination, in paths of learning which have been investigated by superior minds, and with which such adventurous persons are totally unacquainted.

Many ideas that continue to appear today were stated as early as 1670 by John Wilkins, Bishop of Chester and an official of the Royal Society.

He outlined three potential sources of power for a perpetual motion machine, "Chymical [sic] Extractions", "Magnetical Virtues" and "the Natural Affection of Gravity".

[1] The seemingly mysterious ability of magnets to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source has long appealed to inventors.

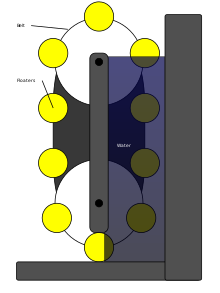

To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at least to Maxwell's demon) is unidirectionality.

These schemes typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality costs energy (requiring Maxwell's demon to perform more thermodynamic work to gauge the speed of the molecules than the amount of energy gained by the difference of temperature caused) or the unidirectionality is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way).

The USPTO Manual of Patent Examining Practice states: With the exception of cases involving perpetual motion, a model is not ordinarily required by the Office to demonstrate the operability of a device.

[30] The United Kingdom Patent Office has a specific practice on perpetual motion; Section 4.05 of the UKPO Manual of Patent Practice states: Processes or articles alleged to operate in a manner which is clearly contrary to well-established physical laws, such as perpetual motion machines, are regarded as not having industrial application.

Distinctions aside, on the macro scale, there are concepts and technical drafts that propose "perpetual motion", but on closer analysis it is revealed that they actually "consume" some sort of natural resource or latent energy, such as the phase changes of water or other fluids or small natural temperature gradients, or simply cannot sustain indefinite operation.

Some examples of such devices include: In some cases a thought experiment appears to suggest that perpetual motion may be possible through accepted and understood physical processes.

Examples include: Despite being dismissed as pseudoscientific, perpetual motion machines have become the focus of conspiracy theories, alleging that they are being hidden from the public by corporations or governments, who would lose economic control if a power source capable of producing energy cheaply was made available.