Robert Fludd

Robert Fludd, also known as Robertus de Fluctibus (17 January 1574 – 8 September 1637), was a prominent English Paracelsian physician with both scientific and occult interests.

[2] He was the son of Sir Thomas Fludd, a high-ranking governmental official (Queen Elizabeth I's treasurer for war in Europe), and Member of Parliament.

His paternal arms goes back to Rhirid Flaidd whose name originates from Welsh meaning bloody or red wolf.

Fludd may have encountered Gwinne, or his writing, during his time at Oxford, providing an additional influence for his later medical philosophy and practice.

After graduating from Christ Church, Fludd moved to London, settling in Fenchurch Street, and making repeated attempts to enter the College of Physicians.

Fludd encountered problems with the College examiners, both because of his unconcealed contempt for traditional medical authorities (he had adopted the views of Paracelsus), and because of his attitude to authority—especially those of the ancients like Galen.

[10] While he followed Paracelsus in his medical views rather than the ancient authorities, he was also a believer that real wisdom was to be found in the writings of natural magicians.

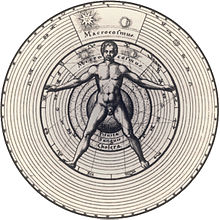

Much of Fludd's writing, and his pathology of disease, centered around the sympathies found in nature between man, the terrestrial Earth, and the divine.

Moreover, the Fluddean tripartite theory concluded that Paracelsus' own conception of the three primary principles—Sulphur, Salt and Mercury—eventually derived from Chaos and Light interacting to create variations of the waters, or Spirit.

Fludd was heavily reliant on scripture; in the Bible, the number three represented the principium formarum, or the original form.

This allowed man and Earth to approach the infinity of God, and created a universality in sympathy and composition between all things.

Fludd's application of his mystically inclined tripartite theory to his philosophies of medicine and science was best illustrated through his conception of the Macrocosm and microcosm relationship.

In succession he defended the Rosicrucians against Andreas Libavius, debated with Kepler, argued against French natural philosophers including Gassendi, and engaged in the discussion of the weapon-salve.

The theological and philosophical claims circulating under this name appear, to these outsiders, to have been more an intellectual fashion that swept Europe at the time of the Counter Reformation.

These manifestos were re-issued several times, and were both supported and countered by numerous pamphlets from anonymous authors: about 400 manuscripts and books were published on the subject between 1614 and 1620.

The furore faded out and the Rosicrucians disappeared from public life until 1710 when the secret cult appears to have been revived as a formal organisation.

Rosicrucianism is also said to have been influential at the time when operative Masonry (a guild of artisans) was being transformed to speculative masonry—Freemasonry—which was a social fraternity, that also originally promoted the scientific and educative view of Comenius, Hartlib, Isaac Newton and Francis Bacon.

It is said by some that he was "the great English mystical philosopher of the seventeenth century, a man of immense erudition, of exalted mind, and, to judge by his writings, of extreme personal sanctity".

He rejected the syncretic move that placed alchemy, cabbala and Christian religion on the same footing; and Fludd's anima mundi.

Fludd's philosophy is presented in Utriusque Cosmi, Maioris scilicet et Minoris, metaphysica, physica, atque technica Historia (The metaphysical, physical, and technical history of the two worlds, namely the greater and the lesser, published in Germany between 1617 and 1621);[22] according to Frances Yates, his memory system (which she describes in detail in The Art of Memory, pp.

Fludd's Opera consist of his folios, not reprinted, but collected and arranged in six volumes in 1638; appended is a Clavis Philosophiæ et Alchimiæ Fluddanæ, Frankfort, 1633.

"[27] He cites Godwin's book as arguing that Fludd was part of the tradition of Christian esotericism that includes Origen and Meister Eckhart.

He finds convincing the argument in Huffman's book that Fludd was not a Rosicrucian but was "a leading advocate of Renaissance Christian Neo-Platonism.