Persepolis Administrative Archives

The archaeological excavations at Persepolis for the Oriental Institute were initially directed by Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934 and carried on from 1934 until 1939 by Erich Schmidt.

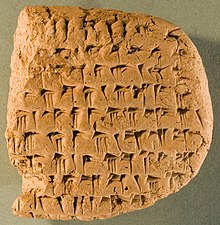

[2] Thousands of clay tablets, fragments and seal impressions in the Persepolis archives are a part of a single administrative system representing continuity of activity and flow of data over more than fifty consecutive years (509 to 457 BCE).

[3] The Persepolis Administrative Archives are the single most important extant primary source for understanding the internal workings of the Persian Achaemenid Empire.

But while these archives have the potential for offering the study of the Achaemenid history based on the sole surviving and substantial records from the heartland of the empire, they are still not fully utilized as such by a majority of historians.

[4] The Persepolis Fortification Archive (PFA), also known as Persepolis Fortification Tablets (PFT, PF), is a fragment of Achaemenid administrative records of receipt, taxation, transfer, storage of food crops (cereals, fruit), livestock (sheep and goats, cattle, poultry), food products (flour, breads and other cereal products, beer, wine, processed fruit, oil, meat), and byproducts (animal hides) in the region around Persepolis (larger part of modern Fars), and their redistribution to gods, the royal family, courtiers, priests, religious officiants, administrators, travelers, workers, artisans, and livestock.

[2] But before the Persepolis archives could have offered any clues to the better understanding of the Achaemenid history, the clay tablets, mostly written in a late dialect of Elamite, an extremely difficult language still imperfectly understood, had to be deciphered.

[2] It was not until 1969, when Richard Hallock published his magisterial edition of 2,087 Elamite Persepolis Fortification Tablets, leading to the renaissance of Achaemenid studies in the 1970s.

[8] The narrow content of the archive, recording only the Achaemenid administration's transactions dealing with foodstuff, must be taken into consideration in regards to the amount of information that can be deduced from them.

[5] Excavations directed by Ernst Herzfeld at Persepolis between 1933 and 1934 for the Oriental Institute, discovered tens of thousands of unbaked clay tablets, badly broken fragments and bullae in March 1933.

The uncleaned tablets and fragments were covered up with wax and after drying, they were wrapped up in cotton and packed in 2,353 sequentially numbered boxes[2] for shipping.

The upper floor of the fortification wall may have collapsed at the time of the Macedonian invasion, both partially destroying the order of the tablets while protecting them until 1933.

All Aramaic texts have seal impressions and are incised with styluses or written in ink with pens or brushes, and are similar to Elamite memoranda.

The number may well increase with study of more records, making Persepolis administrative archives one of the largest collection of imagery in the ancient world, displaying a wide range of styles and skills in the designers and engravers.

There are unique archival records in other languages that attest to the usage of many languages by the administration at Persepolis,[32] such as:[33] Until the discovery of the Persepolis administrative archives, the main sources for information about the Achaemenids were the Greek sources such as Herodotus and ancient historians of Alexander the Great and biblical references in Hebrew Bible, providing a partial and biased view of the ancient Persians.

The archive offers unique opportunity for research on important subjects like organization and status of workers, regional demography, religious practices, royal road, relation between the state institution and private parties, and record management.

[39] Fragmentary finds with Elamite texts from other sites in the Achaemenid Empire point to similar common practices and administrative activities.

The majority view of the academic community as well as international institutions such as UNESCO is the protection of the cultural heritage, exchange and scholarly research must transcend politics.

[7][44][45] The threat of losing the Persepolis Fortification Archive to scholarly research as a result of the litigation since 2004, prompted the Oriental Institute to accelerate and enlarge the PFA Project in 2006, headed by Dr. Matthew Stolper, Professor of Assyriology.

Scholars from various universities, students and volunteers are urgently digitizing the Persepolis Fortification Archive and making it available through online resources for further research worldwide.

[57] Future excavations in the areas currently unexcavated, such as the southeastern part of the Persepolis terrace and mountain fortifications, might yield other archives.