Islam in Iran

The process by which Iranian society became integrated into the Muslim world took place over many centuries, with nobility and city-dwellers being among the first to convert, in spite of notable periods of resistance, while the peasantry and the dehqans (land-owning magnates) took longer to do so.

In the 16th century, the newly enthroned Safavid dynasty initiated a massive campaign to install Shia Islam as Iran's official sect,[1][2][3][4] aggressively proselytizing the faith and forcibly converting the Iranian populace.

The Safavids' actions triggered tensions with the neighbouring Sunni-majority Ottoman Empire, in part due to the flight of non-Shia refugees from Iran.

However, a report by the Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran (GAMAAN) in the same year showed a sharp decline in religiosity in the country, as only 40% of Iranian respondents identified as Muslims.

As Bernard Lewis has quoted[23] "These events have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders.

Despite some resistance from elements of the Zoroastrian clergy and other ancient religions, the anti-Islamic policies of later conquerors like the Il-khanids, the impact of the Christian and secular West in modern times, and the attraction of new religious movements like Babism and the Baháʼí Faith (qq.v.

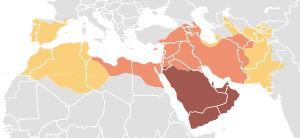

Inheriting a heritage of thousands of years of civilization, and being at the "crossroads of the major cultural highways",[32] contributed to Persia emerging as what culminated into the "Islamic Golden Age".

Ibn Khaldun narrates in his Muqaddimah:[34] It is a remarkable fact that, with few exceptions, most Muslim scholars… in the intellectual sciences have been non-Arabs, thus the founders of grammar were Sibawaih and after him, al-Farsi and Az-Zajjaj.

Under Tughril Beg's successor, Malik Shah (1072–1092), Iran enjoyed a cultural and scientific renaissance, largely attributed to his brilliant Iranian vizier, Nizam al Mulk.

They brought Abu Hamid Ghazali, one of the greatest Islamic theologians, and other eminent scholars to the Seljuk capital at Baghdad and encouraged and supported their work.

In 1500 the Safavid Shah Ismail I undertook the conquering of Iran and Azerbaijan and commenced a policy of forced conversion of Sunni Muslims to Shia Islam.

The oppression and forced conversion of Sunnis would continue, mostly unabated, for the greater part of next two centuries until Iran as well as what is now Azerbaijan became predominantly Shi’ite countries.

[8] As in the case of the early caliphate, Safavid rule had been based originally on both political and religious legitimacy, with the shah being both king and divine representative.

With the later erosion of Safavid central political authority in the mid-17th century, the power of the Shia scholars in civil affairs such as judges, administrators, and court functionaries, began to grow, in a way unprecedented in Shi'ite history.

Likewise, the ulama began to take a more active role in agitating against Sufism and other forms of popular religion, which remained strong in Iran, and in enforcing a more scholarly type of Shi'a Islam among the masses.

According to Professor Roger Savory:[45] In Number of ways the Safavids affected the development of the modern Iranian state: first, they ensured the continuance of various ancient and traditional Persian institutions, and transmitted these in a strengthened, or more 'national', form; second, by imposing Ithna 'Ashari Shi'a Islam on Iran as the official religion of the Safavid state, they enhanced the power of mujtahids.

According to scholar Roy Mottahedeh, one significant change to Islam in Iran during the first half of the 20th century was that the class of ulema lost its informality that allowed it to include everyone from the highly trained jurist to the "shopkeeper who spent one afternoon a week memorizing and transmitting a few traditions."

Laws by Reza Shah that requiring military service and dress in European-style clothes for Iranians, gave talebeh and mullahs exemptions, but only if they passed specific examinations proving their learnedness, thus excluding less educated clerics.

State sanctioned persecution of Bahá’ís follows from them being a "non-recognized" religious minority without any legal existence, classified as "unprotected infidels" by the authorities, and are subject to systematic discrimination on the basis of their beliefs.

One unanticipated effect of theocratic rule in Iran is that in the last couple of decades up to at least 2018, not only have secular people become alienated from the regime, but the state has lost much of its religious credibility among the ultra-religious communities because of widespread corruption, discrimination and its secularisation.

[70] In 2023, Raz Zimmt, an expert on Iran attached to Israel's Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), quoting Iranian sociologist Hamidreza Jalaeipour, argued that 70% of Iranians fall into the category of "silent pragmatist traditionalist majority", which is defined as those who "might approve of religion and aspects of the regime, while rejecting enforced religion and other aspects of the regime.

In the years preceding the Revolution, Iranian Shias generally attached diminishing significance to institutional religion, and by the 1970s there was little emphasis on mosque attendance, even for the Friday congregational prayers.

Wealthy patrons financed construction of hoseiniyehs in urban areas to serve as sites for recitals and performances commemorating the martyrdom of Hussein, especially during the month of Moharram.

[83] Maktabs started to decline in number and importance in the first decades of the twentieth century, once the government began developing a national public school system.

Of the more than 1,100 shrines in Iran, the most important are those for the Eighth Imam, Ali al-Ridha, in Mashhad and for his sister Fatimah bint Musa in Qom, and for Seyyed Rouhollah Khomeini in Tehran.

In addition to the usual shrine accoutrements, it comprises hospitals, dispensaries, a museum, and several mosques located in a series of courtyards surrounding the imam's tomb.

It is a religious endowment by which land and other income-producing property is given in perpetuity for the maintenance of a shrine, mosque, madrassa, or charitable institution such as a hospital, library, or orphanage.

Instead, wealthy and pious Shias chose to give financial contributions directly to the leading ayatollahs in the form of zakat, or obligatory alms.

The clergy, in turn, used the funds to administer their madrassas and to institute various educational and charitable programs, which indirectly provided them with more influence in society.

The access of the clergy to a steady and independent source of funding was an important factor in their ability to resist state controls, and ultimately helped them direct the opposition to the shah.