Persianate society

[24] Persianate culture, especially among the elite classes, spread across the Muslim territories in western, central, and south Asia, although populations across this vast region had conflicting allegiances (sectarian, local, tribal, and ethnic) and spoke many different languages.

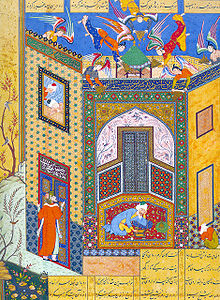

It was spread by poets, artists, architects, artisans, jurists, and scholars, who maintained relations among their peers in the far-flung cities of the Persianate world, from Anatolia to India.

This formed a calcified Persianate structure of thought and experience of the sacred, entrenched for generations, which later informed history, historical memory, and identity among Alid loyalists and heterodox groups labeled by sharia-minded authorities as ghulāt.

The historical change was largely on the basis of a binary model: a struggle between the religious landscapes of late Iranian antiquity and a monotheist paradigm provided by the new religion, Islam.

This duality is symbolically expressed in the Shiite tradition that Husayn ibn Ali, the third Shi'ite Imam, had married Shahrbanu,[25] daughter of Yazdegerd III, the last Sassanid king of Iran.

When the Persian Saffarids from Sistan freed the eastern lands, the Buyyids, the Ziyarids and the Samanids in Western Iran, Mazandaran and the north-east respectively, declared their independence.

[22] The separation of the eastern territories from Baghdad was expressed in a distinctive Persianate culture that became dominant in west, central, and south Asia, and was the source of innovations elsewhere in the Islamic world.

The crowning literary achievement in the early New Persian language was the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), presented by its author Ferdowsi to the court of Mahmud of Ghazni (998–1030).

The powerful effect that this text came to have on the poets of this period is partly due to the value that was attached to it as a legitimizing force, especially for new rulers in the Eastern Islamic world: In the Persianate tradition the Shahnameh was viewed as more than literature.

[30]The Persianate culture that emerged under the Samanids in Greater Khorasan, in northeast Persia and the borderlands of Turkistan exposed the Turks to Persianate culture;[31] The incorporation of the Turks into the main body of the Middle Eastern Islamic civilization, which was followed by the Ghaznavids, thus began in Khorasan; "not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them.

The Seljuqs won a decisive victory over the Ghaznavids and swept into Khorasan; they brought Persianate culture westward into western Persia, Iraq, Anatolia, and Syria.

[citation needed] The Persian jurist and theologian Al-Ghazali was among the scholars at the Seljuq court who proposed a synthesis of Sufism and Sharia, which became the basis for a richer Islamic theology.

The main institutional means of establishing a consensus of the ulama on these dogmatic issues was the Nezamiyeh, better known as the madrasas, named after its founder Nizam al-Mulk, a Persian vizier of the Seljuqs.

[36] First, Persian poets attempted to continue the chronology to a later period, such as the Zafarnamah of the Ilkhanid historian Hamdollah Mostowfi (d. 1334 or 1335), which deals with Iranian history from the Arab conquest to the Mongols and is longer than Ferdowsi's work.

There are however exceptions, such as the Zafar-Nameh of Hamdu'llah Mustaufi a historically valuable continuation of the Shah-nama"[38] and the Shahanshahnamah (or Changiznamah) of Ahmad Tabrizi in 1337–38, which is a history of the Mongols written for Abu Sa'id.

[41] Along with Ferdowsi's and Nizami's works, Amir Khusraw Dehlavi's khamseh came to enjoy tremendous prestige, and multiple copies of it were produced at Persianized courts.

Socially the Persianate world was marked by a system of ethnologically defined elite statuses: the rulers and their soldiery were non-Iranians in origin, but the administrative cadres and literati were Iranians.

[49] The Ottoman Empire's undeniable affiliation with the Persianate world during the first few decades of the sixteenth century are illustrated by the works of a scribe from the Aq Qoyunlu court, Edris Bedlisi.

[50][51] One of the most renowned Persian poets in the Ottoman court was Fethullah Arifi Çelebi, also a painter and historian, and the author of the Süleymanname (or Suleyman-nama), a biography of Süleyman the Magnificent.

[53] According to Hodgson: The rise of Persian (the language) had more than purely literary consequence: it served to carry a new overall cultural orientation within Islamdom.

Gradually a third "classical" tongue emerged, Turkish, whose literature was based on Persian tradition.Toynbee's assessment of the role of the Persian language is worth quoting in more detail, from A Study of History: In the Iranian world, before it began to succumb to the process of Westernization, the New Persian language, which had been fashioned into literary form in mighty works of art...gained a currency as a lingua franca; and at its widest, about the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of the Christian Era, its range in this role extended, without a break, across the face of South-Eastern Europe and South-Western Asia from the Ottoman pashalyq of Buda, which had been erected out of the wreckage of the Western Christian Kingdom of Hungary after the Ottoman victory at Mohacz in A.D. 1526, to the Muslim "successor-states" which had been carved, after the victory of the Deccanese Muslim princes at Talikota in A.D. 1565, out of the carcass of the slaughtered Hindu Empire of Vijayanagar.

For this vast cultural empire the New Persian language was indebted to the arms of Turkish-speaking empire-builders, reared in the Iranian tradition and therefore captivated by the spell of the New Persian literature, whose military and political destiny it had been to provide one universal state for Orthodox Christendom in the shape of the Ottoman Empire and another for the Hindu World in the shape of the Timurid Mughal Raj.

And in this school they continued so long as there was a master to teach them; for the step thus taken at the outset developed into a practice; it became the rule with the Turkish poets to look ever Persia-ward for guidance and to follow whatever fashion might prevail there.

[56] South Asian society was enriched by the influx of Persian-speaking and Islamic scholars, historians, architects, musicians, and other specialists of high Persianate culture who fled the Mongol devastation.

For centuries, Iranian scholar-officials had immigrated to the region where their expertise in Persianate culture and administration secured them honored service within the Mughal Empire.

[citation needed][58]: 24–32 Networks of learned masters and madrasas taught generations of young South Asian men Persian language and literature in addition to Islamic values and sciences.

Furthermore, educational institutions such as Farangi Mahall and Delhi College developed innovative and integrated curricula for modernizing Persian-speaking South Asians.

[58]: 33 They cultivated Persian art, enticing to their courts artists and architects from Bukhara, Tabriz, Herat, Shiraz, and other cities of Greater Iran.

[citation needed] Their works were present in Mughal libraries and counted among the emperors’ prized possessions, which they gave to each other; Akbar and Jahangir often quoted from them, signifying that they had imbibed them to a great extent.

[notes 2] The tendency towards Sufi mysticism through Persianate culture in Mughal court circles is also testified by the inventory of books that were kept in Akbar's library, and are especially mentioned by his historian, Abu'l Fazl, in the Ā’in-ī Akbarī.