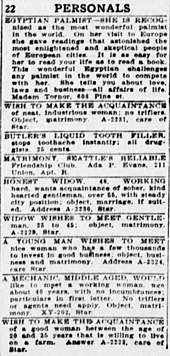

Personal advertisement

Personal ads have been described by a researcher as "a valuable way of finding potential mates for those whose social world has been artificially constrained by contemporary urban life and the demands of modern employment practices".

A London magazine published a satirical marriage ad in 1660, supposedly from a widow urgently in need of "any man that is Able to labour in her Corporation".

[2]: 10–11 The New-England Courant, by brothers James and Benjamin Franklin, printed a satirical marriage ad on its front page on April 13, 1722, ridiculing those who married for money.

[4]: 117 In addition to the offices of the newspapers themselves, various local businesses, such as haberdashers, booksellers, and especially coffee houses, accepted replies to personal ads on behalf of the advertisers.

[2]: 43 As more women began to place ads, more discreet shops and libraries became the preferred intermediaries, as only men frequented coffee houses.

[2]: 65 Possibly the earliest genuine personal ad in the United States was published on February 23, 1759, on page 3 of the Boston Evening-Post.

[3]: 33 From 1866 until the 20th century, the most widely read newspaper in the United States, the New York Herald, printed personal ads on the front page.

Moncrieff's Wanted: a wife, Sarah Gardner's The Advertisement, George Macfarren's Winning a Husband, and Maria Hunter's Fitzroy.

[3]: 23 Newspapers in England reported on successful marriages resulting from personal ads, and printed cautionary tales when an advertiser was made to look foolish or found himself trapped in an unfortunate pairing.

Publishing thousands of personal ads, Matrimonial News served for three decades to "promote marriage and conjugal felicity".

[2]: 174–175 In the United States, the number of personal ads decreased drastically during the 1930s through the 1950s, as dating became more common and acceptable, more men and women were attending college, and couples had greater mobility as cars were more available.

[3]: 177–178 The earliest periodical used for gay personals was The Hobby Directory, established in 1946 by the National Association of Hobbyists for Men and Boys.

[11] Post-World War II, lonely hearts clubs and marriage advisory bureaus became a huge business in West Germany.

Typically placed by lesbians or gay men, the ads seek someone to donate eggs or sperm to enable the advertisers to have children.

[3]: 184–190 While personal ads in publications never gained social acceptance in France, the use of online dating sites are more popular.

Additionally, websites and apps that host personals typically provide automated menus or sortable categories for common information, freeing the advertiser to tailor the narrative portion of the ad to their specific objectives.

[16] Multiple aspects of 19th century society in England combined to make personal ads a viable alternative: the general confinement of women to "private life"; professions such as trade or the military, limiting both the time and social network to meet potential partners; remote locations with small populations; urban expansion that brought many people to the cities, where they were apart from the social and familial networks they had been accustomed to.

[2]: 111-115 In the United States, between 1820 and 1860, populations in cites had increased by 797%, many of the new urbanites lacking social or family networks through which they might meet potential partners.

An 1890 study of female respondents to personal ads in the United States found that they sought independence from societal expectations and a degree of equality in the matter of marriage.

[4]: 138–141 In the early 20th century, answering matrimonial ads was a route to entering the United States after immigration limits became more restrictive.

In 1922, two ships docked in New York with 900 mail-order brides from Turkey, Romania, Armenia, and Greece, fleeing the Greco-Turkish War.

They also used terms reflecting a degree of class consciousness, such as "a young lady of refinement", "respectably connected", and a "good English education".

[2]: 139 Personal ads placed in the 1920s no longer focused on an object of matrimony, but might instead seek companionship, a partner for activities, or sexual dalliances.

[2]: 186 Some abbreviations describe the advertiser and target of the ad by marital status, ethnic group, and sex, such as MWM (married white male) and DBF (divorced black female).

For example, BHP stands for biodata (résumé), horoscope, and photograph; "veg" means vegetarian; and VF is the abbreviation for very fair (light-skinned).

By 1900, most jurisdictions in the United States had criminalized seduction, allowed punitive and exemplary damages for breach of promise actions, and increased recognition of common-law marriages, all of which helped reduce some crimes associated with matrimonial ads.

The most famous "sun and spring" was Gustaf Raskenstam [sv], who used personal ads to defraud over a hundred women of money in the 1940s.

Postal Service warned consumers of fraudulent activity associated with "lonely hearts clubs" in its 1967 Mail Fraud booklet.

[32] In one instance, a man placed personal ads in publications throughout the United States, claiming to be a single Asian female, and eventually bilking over 400 men of approximately $280,000.