Peruvian nitrate monopoly

Alongside this trend, nitrate exports from the Peruvian province of Tarapacá grew, and became an important competitor to guano in the international market.

[3]: 108 In January 1873 the government of Manuel Pardo imposed an estanco, a state control on production and sales of nitrate, but this proved impractical, and the law was shelved in March 1873 before it was ever applied.

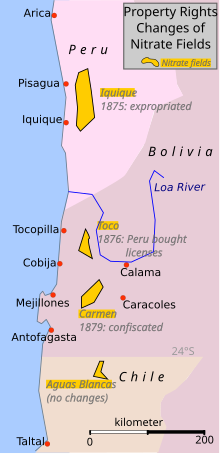

In 1875, as the economic situation deteriorated and Peru's overseas debts increased, the government expropriated the saltpeter industry and imposed a full state monopoly on production and exports.

This treaty had fixed for 25 years the tax rate on the Chilean saltpeter company, in return for Chile's relinquishing of its sovereignty claims over the disputed region of Antofagasta.

Although it is uncertain whether Peru exerted direct pressure on Bolivia to impose this tax, its consequence was the confiscation and auctioning off of the CSFA, the major competitor to Peruvian saltpeter.

[4][5] Some Chilean historians consider that the Peruvian plan to control the price and production of the Bolivian nitrate fields was what ultimately caused the War of the Pacific (1879-1883).

[7] However, most historians consider that the war was actually precipitated by the Chilean government's expansionist foreign policy and its ambitions over the Atacama's mineral wealth in Bolivian and Peruvian territory.

[11]: 65, 77–79 In July 1869 the new government contracted with a French businessman, Auguste Dreyfus to sell two million tons of guano over a six-year period.

This contract gave Peru access to the international financial markets and enabled President José Balta (1868-1872) to raise loans of £36 million in Europe.

The annual revenue of 600,000 soles represented a yield of only one-tenth of the usual 5% or 6% per annum interest on South American investments at the time.

The nitrate producers, who wanted to keep control over production volume and costs, favored a new tax on exports depending on the international price.

The nitrate producers were represented[11]: 106 by Nicolas de Pierola, who voiced a prevailing public mood against the guano traders and the elite of Lima.

As stated by the newspaper El Comercio (Peru) on 30 September 1872, the new law would regulate the nitrate supply, increase the price, eliminate the competition between guano and salitre, and displace Chilean investors from Tarapaca.

[16] On the other hand, it threatened the independence of the producers, who had created their own enclave in a sparsely populated and infertile region physically isolated from the rest of Peru.

In February, in a "fear of gate closing", as firms raised output to increase their quotas, the saltpeter price fell to 18.70 soles per tonne, less than the government had promised to pay to the producers.

[17] Greenhill & Miller cite as reasons for the project's failure the political crisis in Lima, high administrative costs, a lack of trained officials, and Valparaiso's strength as a sales center.

But Peru's (and South America's in general) lack of creditworthiness and the state of European money markets prevented Peru from raising the required £7 million loan in Europe; rather than paying in cash, the Peruvian state had to offer the mine owners two-year certificates bearing 8% interest and a 4% sinking fund in exchange for the properties, although some small salitreras were paid in cash.

[18][3]: 117 Greenhill & Miller agree that "The severity of the financial crisis and the approaching termination of Pardo's presidency unduly hastened its completion.

[1]: 109 [20] Also the long delay (12 months) between proposing and implementing the expropriation encouraged abnormally high output and consequently a low price of saltpeter, beside the Great Depression of British Agriculture.

[1]: 99–100 Beyond that, article IV of the Boundary Treaty between Chile and Bolivia of 1874 explicitly ruled out new or higher taxes upon Chilean companies or persons working in Antofagasta.

On February 6, 1873, a few days after the signing of the Ley del Estanco, the Peruvian senate approved the secret treaty of alliance between Peru and Bolivia; the parliamentary proceedings have disappeared since then.

But William Edmundson states: He cites the catastrophic Peruvian attempt, the uncertainty over the property rights, the immense fiscal and bureaucratic burden, and that for the public opinion in Chile "government ownership of the means of production was regarded as beyond the ideological pale".

While some authors consider that the war interrupted a fiscal reform which was not irrevocably doomed to fail, other historians see it as yet another improvised policy, which the easy guano revenues had generated.

[32] After the war, Chile possessed all guano and saltpeter fields of the Pacific Coast of South America, but never built a state monopoly.