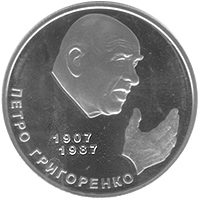

Petro Grigorenko

[5][6] In the words of Joseph Alsop, Grigorenko publicly denounced the "totalitarianism that hides behind the mask of so-called Soviet democracy.

"[7] Petro Grigorenko was born in Borysivka village[8]: 46 in Taurida Governorate, Russian Empire (in present-day Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine).

After the war, being a decorated veteran, he left active career and taught at the Frunze Military Academy, reaching the rank of a Major General.

[16]: 151 Soviet psychiatrists sitting as legally constituted commissions to inquire into his sanity diagnosed him at least three times—in April 1964, August 1969, and November 1969.

[17]: 11 When arrested, Grigorenko was sent to Moscow's Lubyanka prison, and from there for psychiatric examination to the Serbsky Institute[16] where the first commission, which included Snezhnevsky and Lunts, diagnosed him as suffering from the mental disease in the form of a paranoid delusional development of his personality, accompanied by early signs of cerebral arteriosclerosis.

[17]: 11 Lunts, reporting later on this diagnosis, mentioned that the symptoms of paranoid development were "an overestimation of his own personality reaching messianic proportions" and "reformist ideas.

[16]: 152 Grigorenko took part in the defense of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel and sharply protested against the arrests of young writers Alexander Ginzburg, Yuri Galanskov, Alexey Dobrovolsky, and others.

[17]: 12 The diagnosis and evaluation made by the commission was that "Grigorenko's [criminal] activity had a purposeful character, it was related to concrete events and facts...

[24] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hluzman was forced to serve seven years in labor camp for defending Grigorenko against the charge of insanity.

[28] He advised the Tatar activists not to confine their protests to the USSR, but to appeal also to international organizations including the United Nations.

After publishing Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov's book Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party: A Study in the Technology of Power, Grigorenko made and distributed its copies by photographing and typewriting.

[38] On 23 July 1978, Grigorenko made a statement condemning the trials of Soviet dissidents Anatoliy Shcharanskyi, Alexander Ginzburg and Viktoras Petkus.

[41][42][43][44][45] Grigorenko's case confirmed accusations, Stone wrote, that psychiatry in the Soviet Union was at times a tool of political repression.

[46] Petro Grigorenko described his life and views, and his assessment by Soviet psychiatrists and periods of incarceration in prison hospitals in his 1981 memoirs V Podpolye Mozhno Vstretit Tolko Krys… (In the Underground One Can Meet Only Rats…).

[30] In 1982, the book was translated into English by Thomas P. Whitney under the title Memoirs[47] and reviewed by Alexander J. Motyl,[48] Raymond L. Garthoff,[49] John C. Campbell,[50] Adam Ulam,[51] Raisa Orlova and Lev Kopelev.

[4] In 1991, a commission, composed of psychiatrists from all over the Soviet Union and led by Modest Kabanov, then director of the Bekhterev Psychoneurological Institute in St Petersburg, spent six months reviewing Grigorenko's patient files.

They drew up 29 thick volumes of legal proceedings,[1] and in October 1991 reversed the official Soviet diagnosis of Grigorenko's psychiatric condition.

They removed the stigma of being a mental patient and confirmed that there were no grounds for the debilitating treatment he underwent in high security psychiatric hospitals for many years.