Phalanx

: phalanxes or phalanges)[1] was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together.

The term itself, as used today, does not refer to a distinctive military unit or division (e.g., the Roman legion or the contemporary Western-type battalion), but to the type of formation of an army's troops.

Therefore, this term does not indicate a standard combat strength or composition but includes the total number of infantry, which is deployed in a single formation known as a "phalanx".

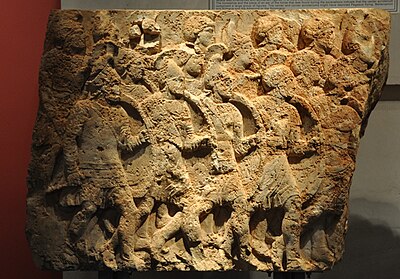

The principles of shield wall and spear hedge were almost universally known among the armies of major civilizations throughout history, and so the similarities may be related to convergent evolution instead of diffusion.

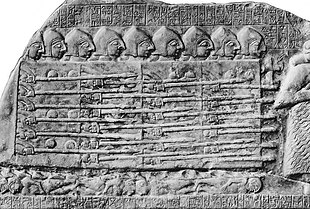

This is further evidenced by the Chigi vase, dated to 650 BC, identifying hoplites armed with aspis, spear, javelins, and other aspects of the panoply.

Rough terrain or hilly regions would have made it difficult to maintain a steady line and would have defeated the purpose of a phalanx.

(The Ancient Greek word φάλαγξ – phalanx – could refer to a tree-trunk or log used as a roller, suggesting an image of physical effort.

[6]) Historians such as Victor Davis Hanson point out that it is difficult to account for exceptionally deep phalanx formations unless they were necessary to facilitate the physical pushing depicted by this theory, as those behind the first two ranks could not take part in the actual spear thrusting.

[7] No Greek art ever depicts anything like a phalanx pushing match, so this hypothesis is a product of educated speculation rather than explicit testimony from contemporary sources and is far from being academically resolved.

Practical difficulties with this theory also include the fact that, in a shoving match, an eight-foot spear is too long to fight effectively or even to parry attacks.

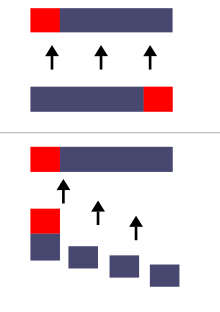

In this case, the phalanx would sacrifice its left side, which typically consisted of allied troops, in an effort to overtake the enemy from the flank.

For this reason, the formation was deliberately organized to group friends and family close together, thus providing a psychological incentive to support one's fellows, and a disincentive, through shame, to panic or attempt to flee.

Now of those, who dare, abiding one beside another, to advance to the close fray, and the foremost champions, fewer die, and they save the people in the rear; but in men that fear, all excellence is lost.

Later, in the classical period, the breastplate became less common, replaced instead with a corselet that some claim was made of linothorax (layers of linen glued together), or perhaps of leather, sometimes covered in whole or in part with overlapping metal scales.

[16] These changes reflected the balancing of mobility with protection, especially as cavalry became more prominent in the Peloponnesian War[17] and the need to combat light troops, which were increasingly used to negate the hoplite's role as the primary force in battle.

Some archaeologists have pointed out that bronze armour does not actually provide as much protection from direct blows as more extensive corselet padding, and have suggested its continued use was a matter of status for those who could afford it.

[20] Hoplites carried a circular shield called an aspis made from wood and covered in bronze, measuring roughly a metre (3.3 feet) in diameter.

This medium-sized shield (fairly large for the period considering the average male height) was made possible partly by its dish-like shape, which allowed it to be supported with the rim on the shoulder.

Despite its mobility, protective curve, and double straps the circular shape created gaps in the shield wall at both its top and bottom.

In order to minimize the bottom gaps, thick leather curtains were used but only by an unknown percentage of the hoplites, possibly only in the first row since there were disadvantages as well: considerable weight on an already heavy shield and a certain additional cost.)

The great length of the pike was balanced by a counterweight at the rear end, which also functioned as a butt-spike, allowing the sarissa to be planted into the ground.

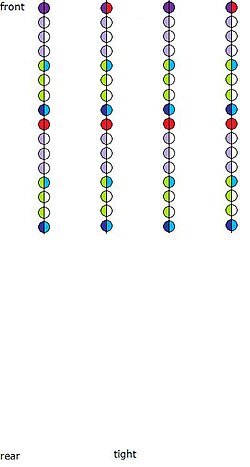

In synaspismos, the rank depth was half that of a normal phalanx and the width each man occupied was as small as 0.45 metres (1.5 ft).

Facing the much larger army of Darius I, the Athenians thinned out their phalanx and consequently lengthened their front, to avoid being outflanked.

Meanwhile, the centre and right flank of the Theban line were echeloned back, from the opposing phalanx, keeping the weakened parts of the formation from being engaged.

An example of this would be the Battle of Lechaeum, where an Athenian contingent led by Iphicrates routed an entire Spartan mora (a unit of 500–900 hoplites).

Theoretically indestructible from the front, its flanks and rear were very vulnerable, and once engaged it may not easily disengage or redeploy to face a threat from those directions.

The Macedonian phalanx could also lose its cohesion without proper coordination or while moving through broken terrain; doing so could create gaps between individual blocks/syntagmata, or could prevent a solid front within those sub-units as well, causing other sections of the line to bunch up.

[24] In this event, as in the battles of Cynoscephalae and Pydna, the phalanx became vulnerable to attacks by more flexible units – such as Roman legionary centuries, which were able to avoid the sarissae and engage in hand-to-hand combat with the phalangites.

This then implies that the hoplites ranks closer to the front must be mentally prepared to replace their fallen comrade and adapt to his new position without disrupting the structure of the frontline.

The combination disorganised the Scottish phalanxes and permitted effective attacks by English longbowmen, and soldiers wielding shorter, handier polearms called bills.

32 men each in loose formation

(2 m apart, 32 ranks)

each file 1 m apart (16 ranks)

each file 0.5 m apart, eight ranks.

Rightmost file not shown.

Bottom: the diagonal phalanx utilised by the Thebans under Epaminondas. The strong left wing advanced while the weak right wing retreated or remained stationary.