Roman infantry tactics

This approach included a tendency towards standardization and systematization, practical borrowing, copying and adapting from outsiders, flexibility in tactics and methods, a strong sense of discipline, a ruthless persistence which sought comprehensive victory, and a cohesion brought about by the idea of Roman citizenship under arms – embodied in the legion.

The mule carried a variety of equipment and supplies, e.g. a mill for grinding grain, a small clay oven for baking bread, cooking pots, spare weapons, waterskins, and tents.

This consisted of ten stone-throwing onagers and twenty bolt-shooting ballistas; in addition, each of the legion's centuries had its own scorpio bolt thrower (sixty total), together with supporting wagons to carry ammunition and spare parts.

[11] According to Vegetius, during the four-month initial training of a Roman legionary, marching skills were taught before recruits ever handled a weapon, since any formation would be split up by stragglers at the back or soldiers trundling along at differing speeds.

[16] Roman logistics were among some of the best in the ancient world over the centuries, from the deployment of purchasing agents to systematically buy provisions during a campaign, to the construction of roads and supply caches, to the rental of shipping if the troops had to move by water.

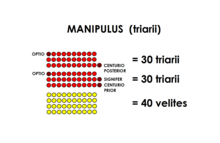

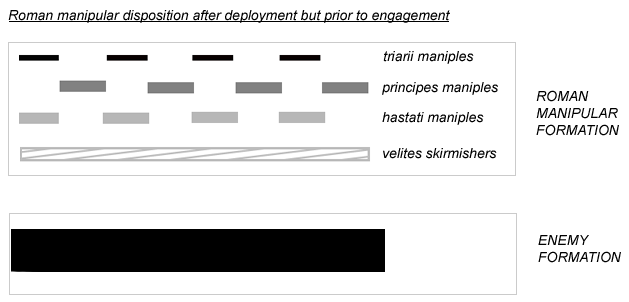

It often took some time for the final array of the host, but when accomplished the army's grouping of legions represented a formidable fighting force, typically arranged in three lines with a frontage as long as one mile (about 1.5 km).

[25] A general three-line deployment was to remain over the centuries, although the so-called Marian reforms phased out most divisions based on age and class, standardized weapons, and reorganized the legions into larger manoeuvre units like cohorts.

Most ancient armies deployed in shallower formations which might deepen their ranks heavily to add both stamina and shock power, but their general approach still favoured one massive line, as opposed to the deep Roman arrangement.

The advantage of the Roman system is that it allowed the continual funnelling or metering of combat power forward over a longer period – massive, steadily renewed pressure to the front – until the enemy broke.

[37] Whatever structure the actual formation took, however, the ominous funnelling or surge of combat power up to the front remained constant: Whatever the deployment, the Roman army was marked by flexibility, strong discipline, and cohesion.

While defensive configurations were sometimes used, the phalanx was most effective when it was moving forward in attack, either in a frontal charge or in "oblique" or echeloned order against an opposing flank, as the victories of Alexander the Great and Theban innovator Epaminondas attest.

[25] Hannibal's deployment at Zama appears to recognize this – hence the Carthaginian also used a deep three-layer approach, sacrificing his first two lower quality lines and holding back his combat-hardened veterans of Italy for the final encounter.

When the Romans faced phalangite armies, the legions often deployed the velites in front of the enemy with the command to contendite vestra sponte (attack), presumably with their javelins, to cause confusion and panic in the solid blocks of phalanxes.

The later debacles at Lake Trasimene and Cannae, forced the proud Romans to avoid battle, shadowing the Carthaginians from the high ground of the Apennines, unwilling to risk a significant engagement on the plains where the enemy cavalry held sway.

From a military standpoint, however, they seem to have shared certain general characteristics: tribal polities with a relatively small and lesser elaborated state structure, light weaponry, fairly unsophisticated tactics and organization, a high degree of mobility, and inability to sustain combat power in their field forces over a lengthy period.

Though popular accounts celebrate the legions and an assortment of charismatic commanders quickly vanquishing massive hosts of "wild barbarians",[46] Rome suffered a number of early defeats against such tribal armies.

Tacitus in his Annals reports that the Roman commander Germanicus recognized that continued operations in Gaul would require long trains of men and material to come overland, where they would be subject to attack as they traversed the forests and swamps.

A charge by the Nervi tribe through a gap between the legions, however, almost turned the tide again, as the onrushing warriors seized the Roman camp and tried to outflank the other army units engaged with the rest of the tribal host.

Under their war leader Vercingetorix, the Gauls pursued what some modern historians have termed a "persisting" or "logistics strategy" – a mobile approach relying not on direct open field clashes, but avoidance of major battle, "scorched earth" denial of resources, and the isolation and piecemeal destruction of Roman detachments and smaller unit groupings.

[65] The Gauls were unable to sustain their strategy and Vercingetorix was to become trapped in Alesia, facing not divided sections or detachments of the Roman army but Caesar's full force of approximately 70,000 men (50,000 legionaries plus numerous additional auxiliary cavalry and infantry).

The Gauls gave battle at a place where they were inadequately provisioned for an extended siege, and where Caesar could bring his entire field force to bear on a single point without them being dissipated, and where his lines of supply were not effectively interdicted.

[73] In Spain, resources were thrown at the problem until it yielded over 150 years later – a slow, harsh grind of endless marching, constant sieges and fighting, broken treaties, burning villages and enslaved captives.

"The country was wasted by fire and sword fifty miles round, nor sex nor age found mercy; places sacred and profane had the equal lot of destruction, all razed to the ground ..." (Tacitus, Annals.)

The Parthians also conducted a "scorched earth" policy against the Romans, refusing major set-piece encounters, while luring them deeper on to the unfavorable ground, where they would lack water supplies and a secure line of retreat.

[78] Crassus' force was systematically dismembered by the smaller Parthian army, who surprised Roman expectations that they would run out of arrows, by arranging for a supply train of ammunition borne by thousands of camels.

Nevertheless, some historians emphasize that the final demise of Rome was due to "military" defeat, however plausible (or implausible) the plethora of theories advanced by some scholars, ranging from declining tax bases, to class struggle, to mass lead poisoning.

Other modern scholars (Ferrill et al.) also see the pullback as a strategic mistake, arguing that it left lower quality "second string" limitanei forces to stop an enemy until the distant mobile reserve arrived.

While the drop in quality did not happen immediately, it is argued that over time, the limitanei declined into lightly armed, static watchman type troops that were of dubious value against increasing barbarian marauders on the frontiers.

Some scholars challenge the notion that a "mobile reserve" in the modern military sense existed in the Roman Empire, and instead argue that the shifts in an organization represent a series of field armies deployed in various areas as needed, particularly in the East.

[93] At the Battle of Châlons (circa 451 AD) Attila the Hun rallied his troops by mocking the once-vaunted Roman infantry, alleging that they merely huddled under a screen of protective shields in close formation.