Phan Đình Phùng

He was the most prominent of the Confucian court scholars involved in anti-French military campaigns in the 19th century and was cited after his death by 20th-century nationalists as a national hero.

He was renowned for his uncompromising will and principles—on one occasion,[1] he refused to surrender even after the French had desecrated his ancestral tombs and had arrested and threatened to kill his family.

Born into a family of mandarins from Hà Tĩnh Province, Phan continued his ancestors' traditions by placing first in the metropolitan imperial examinations in 1877.

Phan quickly rose through the ranks under Emperor Tự Đức of the Nguyễn dynasty, gaining a reputation for his integrity and uncompromising stance against corruption.

Along with Thuyết, Phan organised rebel armies as part of the Cần Vương movement, which sought to expel the French and install the boy Emperor Hàm Nghi at the head of an independent Vietnam.

Phan and his military assistant Cao Thắng continued their guerrilla campaign, building a network of spies, bases and small weapons factories.

[4] Phan was never known for his scholarly abilities; it was his reputation for principled integrity that led to his quick rise through the ranks under the reign of Emperor Tự Đức.

[2] He was first appointed as a district mandarin in Ninh Bình Province, where he punished a Vietnamese Roman Catholic priest, who, with the tacit support of French missionaries, had harassed local non-Catholics.

Amid the diplomatic controversy that followed, he avoided blaming the unpopular alliance between Vietnamese Catholics and the French on Catholicism itself, stating that the partnership had arisen out of the military and political vulnerabilities of Vietnam's imperial government.

He earned the ire of many of his colleagues, but the trust of the emperor, by revealing that the vast majority of the court mandarins were making a mockery of a royal edict to engage in regular rifle practice.

[19] The teenage Kiến Phúc ascended the throne, but was poisoned by his adoptive mother Học Phi—one of Tự Đức's wives—whom he caught having intercourse with Tường.

[20] Thuyết had already decided to place Hàm Nghi at the head of the Phong Trào Cần Vương (Aid the King Movement), which sought to end French rule with a royalist rebellion.

[20][22] In any case, the Cần Vương revolt started on July 5, 1885, when Thuyết launched a surprise attack against the colonial forces after a diplomatic confrontation with the French.

[22][26] Phan initially rallied support from his native village and set up his headquarters on Mount Vũ Quang,[27] which overlooked the coastal French fortress at Hà Tĩnh.

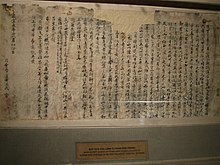

Phan was reported to have replied:[29] (Original Vietnamese)[30] Nay tôi chỉ có một ngôi mộ rất to nên giữ là nước Việt Nam.

"[28] This incident and Phan's response are often cited as one of the reasons why he was so admired by the populace and among future generations of Vietnamese anti-colonialists: he adhered to the highest personal standards of patriotism.

The only details in which they were regarded as being defective were in the tempering of the springs, which were improvised with umbrella spokes, and the lack of rifling in the barrels, which curtailed range and accuracy.

[7] The Vietnamese could not rely on China to give them material support, and other European powers such as Portugal, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom were unwilling to sell them weapons for various reasons.

Thus, Phan had to explore overland routes to procure weapons from Siamese sources—using seafaring transport was impossible due to the presence of the French Navy.

[31] It is unclear if Phan himself went to Thailand,[31] but a young female supporter named Cô Trâm [vi] was his designated arms buyer in Tha Uthen, which boasted a substantial expatriate Vietnamese community.

Phan's men foraged and sold cinnamon bark to raise funds, while lowland peasants donated spare metals for the production of weapons.

In the spring of 1892, a major French sweep of Hà Tĩnh failed, and in August, Cao Thắng seized the initiative with a bold counterattack on the provincial capital.

The rebels broke into the prison and freed their compatriots, killing a large number of the Vietnamese soldiers who defended the penitentiary as members of the French colonial forces.

[37] The troops were eager, but after overpowering several small posts en route, the main force was pinned down while attacking the French fort of No on September 9, 1893.

[40] Although Phan had previously stated that he was not expecting ultimate success,[28] the guerrilla leader thought that it was important to keep pressuring the French in order to demonstrate to the populace that there was an alternative to what he felt was a defeatist attitude from the Huế court.

In an attempt to force Phan to surrender, the French arrested his family and desecrated the tombs of his ancestors, publicly displaying the remains in Hà Tĩnh.

[43][44] According to Marr, "Phan Dinh Phung's reply was a classic in savage understatement, utilizing standard formalism in the interest of propaganda, with deft denigration of his opponent".

He cited defensive wars against the Han, Tang, Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties, asking why a country "a thousand times more powerful" could not annex Vietnam.

[47] With Phan's rebuke in his hands, Khải translated both documents into French and presented them to De Lanessan, proposing that it was time for the final "destruction of this scholar gentry rebellion".

[54] Since then, Hồ's communists have portrayed themselves as the modern day incarnations of revered nationalist leaders such as Phan, Trương Định and Emperors Lê Lợi and Quang Trung, who expelled Chinese forces from Vietnam.