Phase curve (astronomy)

In ephemeris generation, the phase curve is used in conjunction with the distances from the object to the Sun and the Earth to calculate the apparent magnitude.

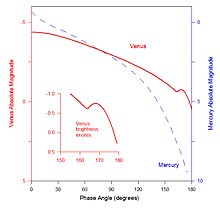

The phase curve of Mercury is very steep, which is characteristic of a body on which bare regolith (soil) is exposed to view.

The width of the opposition surge for Mercury indicates that both the compaction state of the regolith and the distribution of particle sizes on the planet are similar to those on the Moon.

[1] Early visual observations contributing to the phase curve of Mercury were obtained by G. Muller[4] in the 1800s and by André-Louis Danjon[5][6][7] in the mid-twentieth century.

Some of these early data were analyzed by G. de Vaucouleurs,[9][10] summarized by D. Harris[11] and used for predicting apparent magnitudes in the Astronomical Almanac[12] for several decades.

The apparent brightness of Mercury as seen from Earth is greatest at phase angle 0° (superior conjunction with the Sun) when it can reach magnitude −2.6.

Venus exhibits a brightness surge near phase angle 170°, when it is a thin crescent, due to forward scattering of sunlight by droplets of sulfuric acid that are above the planet's cloud tops.

As with Mercury, these new data are the major source of the phase curve used in the Astronomical Almanac[13] for predicting apparent magnitudes.

The phase curve of the Earth has not been determined as accurately as those for Mercury and Venus because its integrated brightness is difficult to measure from the surface.

P. Goode and colleagues at Big Bear Solar Observatory have measured the earthshine[16] and T. Livengood of NASA analyzed the EPOXI data.

The rotation of bright and dark surface markings across its disk and variability of its atmospheric state (including its dust storms) superimpose variations on the phase curve.

Hubble Space Telescope and Cassini spacecraft images have been analyzed in an attempt to characterize the ring particles based on their phase curves.

[22][23][24][25] The phase curve of the Moon approximately resembles that of Mercury due to the similarities of the surfaces and the lack of an atmosphere on either body.

Additionally, J. Bailey[36] has pointed out that phase curve anomalies such as the brightness excess of Venus could be useful indicators of atmospheric constituents such as water, which might be essential to life in the universe.

However, in a blind test M. Shepard and P. Helfenstein[37] found no strong evidence that a particular set of Hapke parameters derived from photometric data could uniquely reveal the physical state of laboratory samples.