Philippine–American War

In retaliation for Filipino guerrilla warfare tactics, the U.S. carried out reprisals and scorched earth campaigns and forcibly relocated many civilians to concentration camps, where thousands died.

[53] In July 1898, three months into the Spanish-American War, U.S. command began suspecting Aguinaldo was secretly negotiating with Spanish authorities to gain control of Manila without U.S. assistance,[54] reporting that the rebel leader was restricting delivery of supplies to U.S.

[61] The full text of the protocol was not made public until November 5, but Article III read: "The United States will occupy and hold the City, Bay, and Harbor of Manila, pending the conclusion of a treaty of peace, which shall determine the control, disposition, and government of the Philippines.

[65][66] This provoked General Anderson to send Aguinaldo a letter saying, "In order to avoid the very serious misfortune of an encounter between our troops, I demand your immediate withdrawal with your guard from Cavite.

[67] An insurgent officer in Cavite at the time reported on his record of services that he: "took part in the movement against the Americans on the afternoon of the 24th of August, under the orders of the commander of the troops and the adjutant of the post".

"[72] McKinley concluded after much consideration that returning the Philippines to Spain would have been "cowardly and dishonorable," that turning them over to "commercial rivals" of the United States would have been "bad business and discreditable," and that the Filipinos "were unfit for self-government.

[78] On December 21, 1898, McKinley issued a proclamation of "benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule" for "the greatest good of the governed".

It enjoined military commander Major General Elwell Stephen Otis to inform Filipinos that "in succeeding to the sovereignty of Spain" the authority of the United States "is to be exerted for the securing of the persons and property of the people of the islands and for the confirmation of all their private rights and relations".

The proclamation specified that "it will be the duty of the commander of the forces of occupation to announce and proclaim in the most public manner that we come, not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights".

The next day the government officials were surprised to learn that messages to General Otis to deal mildly with the rebels and not to force a conflict had become known to Agoncillo, and cabled by him to Aguinaldo.

8 Jan., 1899, 9:40 p.m.: In consequence of the order of General Rios to his officers, as soon as the Filipino attack begins the Americans should be driven into the Intramuros district and the walled city should be set on fire.

On January 31, 1899, the Minister of Interior of the Republic, Teodoro Sandiko, signed a decree saying that President Aguinaldo had directed that all idle lands be planted to provide food, in view of impending war with the Americans.

[108] In the U.S., President McKinley had created a commission chaired by Jacob Gould Schurman on January 20[e] and tasked it to study the situation in the Philippines and make recommendations on how the U.S. should proceed.

Beginning on September 14, 1899, Aguinaldo accepted the advice of General Gregorio del Pilar and authorized the use of guerrilla warfare tactics in subsequent military operations in Bulacan.

[129] The Philippine Army began staging bloody ambushes and raids, such as the guerrilla victories at Paye, Catubig, Makahambus Hill, Pulang Lupa, and Mabitac.

[132] On March 23, 1901, General Frederick Funston and his troops captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela, with the help of some Filipinos (called the Macabebe Scouts after their home locale[133][134]) who had joined the Americans.

[135] On April 1, 1901, at Malacañang Palace in Manila, Aguinaldo swore an oath accepting the authority of the United States over the Philippines and pledging his allegiance to the American government.

"The lesson which the war holds out and the significance of which I realized only recently, leads me to the firm conviction that the complete termination of hostilities and a lasting peace are not only desirable but also absolutely essential for the well-being of the Philippines.

[144] On July 4, 1902, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. presidency, proclaimed officially that the war was at an end and extended a full and complete pardon and amnesty to all persons in the Philippine Archipelago who had participated in the conflict.

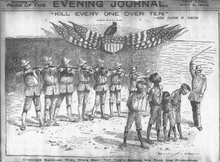

For example, In 1901, the Manila correspondent of the Philadelphia Ledger wrote: The present war is no bloodless, opera bouffe engagement; our men have been relentless, have killed to exterminate men, women, children, prisoners and captives, active insurgents and suspected people from lads of ten up, the idea prevailing that the Filipino as such was little better than a dog...[165]Reports from returning soldiers stated that upon entering a village, American soldiers would ransack every house and church and rob the inhabitants of everything of value, while Filipinos who approached the battle line waving a flag of truce were fired upon.

Brigadier General Joseph Wheeler insisted that Filipinos had mutilated their own dead, murdered women and children, and burned down villages, solely to discredit American soldiers.

[183] Apolinario Mabini, in his autobiography, confirms these offenses, stating that Aguinaldo did not punish Filipino troops who engaged in war rape, burned and looted villages, or stole and destroyed private property.

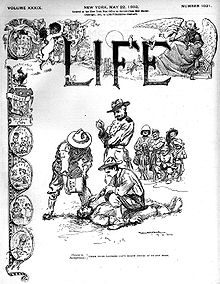

[188] Testimony before the Lodge Committee stated that natives were given the water cure, "... in order to secure information of the murder of Private O'Herne of Company I, who had been not only killed, but roasted and otherwise tortured before death ensued.

[190] Worcester recounts two specific Filipino atrocities as follows: A detachment, marching through Leyte, found an American who had disappeared a short time before crucified, head down.

We cannot from any point of view escape the responsibilities of government which our sovereignty entails; and the commission is strongly persuaded that the performance of our national duty will prove the greatest blessing to the peoples of the Philippine Islands.

[198] The commission established a civil service and a judicial system that included a Supreme Court, and a legal code was drawn up to replace obsolete Spanish ordinances.

[208] U.S. Army Captain Matthew Arlington Batson formed the Macabebe Scouts[209] as a native guerrilla force to fight the insurgency from among a tribe of that name having a history of antipathy with Tagalogs.

Organized and initially commanded by Brigadier General Henry Tureman Allen, the Philippine Constabulary gradually took responsibility for suppressing hostile forces' activities.

Though most fighting in the Philippines had ceased by the time of Aguinaldo's capture in March 1901, guerrilla activity continued in some areas, notably in Samar under Lukbán and in Batangas under Malvar[h].

The rebellion continued until the Battle of Bud Bagsak in June 1913, in which Moro forces under Datu Amil were defeated by US troops led by Brigadier General John J. Pershing.