Phonological development

[1] Furthermore, the child has to be able to distinguish the sequence “cup” from “cub” in order to learn that these are two distinct words with different meanings.

The acquisition of native language phonology begins in the womb[2] and isn't completely adult-like until the teenage years.

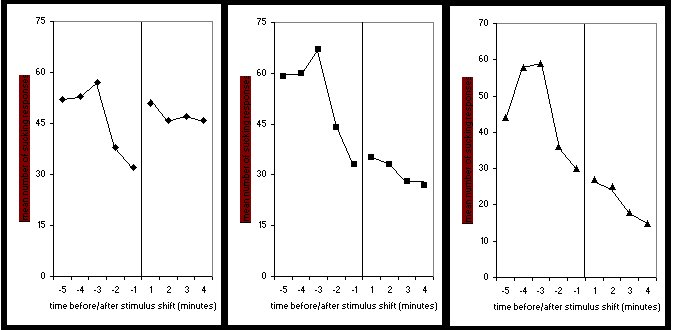

[6] This shows that between 1 and 4 months of age, infants improve in tracking the suprasegmental information in the speech directed at them.

For example, if English-learning infants are exposed to a prevoiced /d/ to voiceless unaspirated /t/ continuum (similar to the /d/ - /t/ distinction in Spanish) with the majority of the tokens occurring near the endpoints of the continuum, i.e., showing extreme prevoicing versus long voice onset times (bimodal distribution) they are better at discriminating these sounds than infants who are exposed primarily to tokens from the center of the continuum (unimodal distribution).

[9] These results show that at the age of 6 months infants are sensitive to how often certain sounds occur in the language they are exposed to and they can learn which cues are important to pay attention to from these differences in frequency of occurrence.

At 6 months, infants are also able to make use of prosodic features of the ambient language to break the speech stream they are exposed to into meaningful units, e.g., they are better able to distinguish sounds that occur in stressed vs. unstressed syllables.

[12] While children generally don't understand the meaning of most single words yet, they understand the meaning of certain phrases they hear a lot, such as “Stop it,” or “Come here.”[13] Infants can distinguish native from nonnative language input using phonetic and phonotactic patterns alone, i.e., without the help of prosodic cues.

Stark (1980) distinguishes five stages of early speech development:[16] These earliest vocalizations include crying and vegetative sounds such as breathing, sucking or sneezing.

Infants produce a variety of vowel- and consonant-like sounds that they combine into increasingly longer sequences.

Children are able to distinguish newly learned ‘words’ associated with objects if they are not similar-sounding, such as ‘lif’ and ‘neem’.

[22] So, while children at this age are able to distinguish monosyllabic minimal pairs at a purely phonological level, if the discrimination task is paired with word meaning, the additional cognitive load required by learning the word meanings leaves them unable to spend the extra effort on distinguishing the similar phonology.

At 18–20 months infants can distinguish newly learned ‘words’, even if they are phonologically similar, e.g. ‘bih’ and ‘dih’.

[23] This result has also been taken to suggest that infants move from a word-based to a segment-based phonological system around 18 months of age.

[24][25] Children as young as 15 months can complete this task successfully if the experiment is conducted with fewer objects.

[26] This task shows that children aged 15 to 20 months can assign meaning to a new word after only a single exposure.

[27] At 2 years, infants show first signs of phonological awareness, i.e., they are interested in word play, rhyming, and alliterations.

For example, only about half of the 4- and 5-year-olds tested by Liberman et al. (1974) were able to tap out the number of syllables in multisyllabic words, but 90% of the 6-year-olds were able to do so.

Liberman et al. found that no 4-year-olds and only 17% of 5-year-olds were able to tap out the number of phonemes (individual sounds) in a word.

One reason why phoneme awareness gets much better once children start school is because learning to read provides a visual aid as how to break up words into their smaller constituents.

Children in a study by Vogel and Raimy (2002)[31] were asked to show which of two pictures (i.e., a dog or a sausage) was being named.

[32] The lexical items they produce are probably stored as whole words rather than as individual segments that get put together online when uttering them.

[13] Influences on the rate of word learning, and thus on the wide range of vocabulary sizes of children of the same age, include the amount of speech children are exposed to by their caregivers as well as differences in how rich the vocabulary in the speech a child hears is.

Children also seem to build up their vocabulary faster if the speech they hear is related to their focus of attention more often.

[37] Their ability to produce complex sound sequences and multisyllabic words continues to improve throughout middle childhood.

[1] The limited movement possible by the infant jaw and mouth might be responsible for the typical consonant-vowel (CV) alternation in babbling and it has even been suggested that the predominance of CV syllables in the languages of the world might evolutionarily have been caused by this limited range of movements of the human vocal organs.

The limbic system is known to be involved in the expression of emotion, and cooing in infants is associated with a feeling of contentedness.

The motor cortex, finally, which develops later than the abovementioned structures may be necessary for canonical babbling, which start around 6 to 9 months of age.