Photoelasticity

The photoelastic phenomenon was first discovered by the Scottish physicist David Brewster, who immediately recognized it as stress-induced birefringence.

Their book Treatise on Photoelasticity, published in 1930 by Cambridge Press, became a standard text on the subject.

[4] At the same time, much development occurred in the field – great improvements were achieved in technique, and the equipment was simplified.

With refinements in the technology, photoelastic experiments were extended to determining three-dimensional states of stress.

In parallel to developments in experimental technique, the first phenomenological description of photoelasticity was given in 1890 by Friedrich Pockels,[5] however this was proved inadequate almost a century later by Nelson & Lax[6] as the description by Pockels only considered the effect of mechanical strain on the optical properties of the material.

With the advent of the digital polariscope – made possible by light-emitting diodes – continuous monitoring of structures under load became possible.

This led to the development of dynamic photoelasticity, which has contributed greatly to the study of complex phenomena such as fracture of materials.

[10] Photoelasticity can successfully be used to investigate the highly localized stress state within masonry[11][12][13] or in proximity of a rigid line inclusion (stiffener) embedded in an elastic medium.

Dynamic photoelasticity integrated with high-speed photography is utilized to investigate fracture behavior in materials.

[15] Another important application of the photoelasticity experiments is to study the stress field around bi-material notches.

[16] Bi-material notches exist in many engineering application like welded or adhesively bonded structures.

[citation needed] For example, some elements of Gothic cathedrals previously thought decorative were first proved essential for structural support by photoelastic methods.

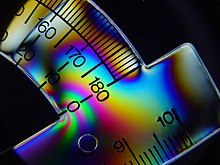

Birefringence is a phenomenon in which a ray of light passing through a given material experiences two refractive indices.

Information such as maximum shear stress and its orientation are available by analyzing the birefringence with an instrument called a polariscope.

Assuming a thin specimen made of isotropic materials, where two-dimensional photoelasticity is applicable, the magnitude of the relative retardation is given by the stress-optic law:[20] where Δ is the induced retardation, C is the stress-optic coefficient, t is the specimen thickness, λ is the vacuum wavelength, and σ1 and σ2 are the first and second principal stresses, respectively.

The polariscope combines the different polarization states of light waves before and after passing the specimen.

The first step is to build a model, using photoelastic materials, which has geometry similar to the real structure under investigation.

[citation needed] Isochromatics are the loci of the points along which the difference in the first and second principal stress remains the same.

[citation needed] The working principle of a two-dimensional experiment allows the measurement of retardation, which can be converted to the difference between the first and second principal stress and their orientation.

[22] Several theoretical and experimental methods are utilized to provide additional information to solve individual stress components.

[citation needed] The fringe pattern in a plane polariscope setup consists of both the isochromatics and the isoclinics.

The analyzer-side quarter-wave plate converts the circular polarization state back to linear before the light passes through the analyzer.

The same device functions as a plane polariscope when quarter wave plates are taken aside or rotated so their axes parallel to polarization axes