Infinitesimal strain theory

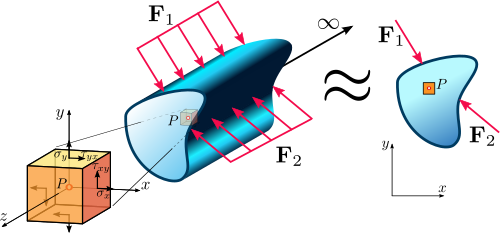

In continuum mechanics, the infinitesimal strain theory is a mathematical approach to the description of the deformation of a solid body in which the displacements of the material particles are assumed to be much smaller (indeed, infinitesimally smaller) than any relevant dimension of the body; so that its geometry and the constitutive properties of the material (such as density and stiffness) at each point of space can be assumed to be unchanged by the deformation.

With this assumption, the equations of continuum mechanics are considerably simplified.

It is contrasted with the finite strain theory where the opposite assumption is made.

The infinitesimal strain theory is commonly adopted in civil and mechanical engineering for the stress analysis of structures built from relatively stiff elastic materials like concrete and steel, since a common goal in the design of such structures is to minimize their deformation under typical loads.

However, this approximation demands caution in the case of thin flexible bodies, such as rods, plates, and shells which are susceptible to significant rotations, thus making the results unreliable.

In such a linearization, the non-linear or second-order terms of the finite strain tensor are neglected.

This linearization implies that the Lagrangian description and the Eulerian description are approximately the same as there is little difference in the material and spatial coordinates of a given material point in the continuum.

Therefore, the material displacement gradient tensor components and the spatial displacement gradient tensor components are approximately equal.

Also, from the general expression for the Lagrangian and Eulerian finite strain tensors we have

Consider a two-dimensional deformation of an infinitesimal rectangular material element with dimensions

) we can write the tensor in terms of components with respect to those base vectors as

) coordinate system are called the principal strains and the directions

If we are given the components of the strain tensor in an arbitrary orthonormal coordinate system, we can find the principal strains using an eigenvalue decomposition determined by solving the system of equations

along which the strain tensor becomes a pure stretch with no shear component.

Actually, if we consider a cube with an edge length a, it is a quasi-cube after the deformation (the variations of the angles do not change the volume) with the dimensions

An octahedral plane is one whose normal makes equal angles with the three principal directions.

[citation needed] The normal strain on an octahedral plane is given by

This quantity is work conjugate to the equivalent stress defined as

represents a system of six differential equations for the determination of three displacements components

Thus, a solution does not generally exist for an arbitrary choice of strain components.

Therefore, some restrictions, named compatibility equations, are imposed upon the strain components.

These constraints on the strain tensor were discovered by Saint-Venant, and are called the "Saint Venant compatibility equations".

If the elastic medium is visualised as a set of infinitesimal cubes in the unstrained state, after the medium is strained, an arbitrary strain tensor may not yield a situation in which the distorted cubes still fit together without overlapping.

In engineering notation, In real engineering components, stress (and strain) are 3-D tensors but in prismatic structures such as a long metal billet, the length of the structure is much greater than the other two dimensions.

(if the length is the 3-direction) are constrained by nearby material and are small compared to the cross-sectional strains.

A skew symmetric second-order tensor has three independent scalar components.

then the material undergoes an approximate rigid body rotation of magnitude

From an important identity regarding the curl of a tensor we know that for a continuous, single-valued displacement field

The components of the strain tensor in a cylindrical coordinate system are given by:[2]

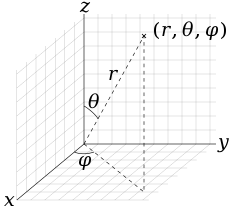

The components of the strain tensor in a spherical coordinate system are given by [2]