Pontius Pilate

On the basis of events which were documented by the second-century pagan philosopher Celsus and the Christian apologist Origen, most modern historians believe that Pilate simply retired after his dismissal.

Many of these legends connected Pilate's place of birth or death to particular locations around Western Europe, such as claiming his body was buried in a particularly dangerous or cursed local area.

[23] His praenomen (first name) is unknown;[24] his cognomen Pilatus might mean "skilled with the javelin (pilum)", but it could also refer to the pileus or Phrygian cap, possibly indicating that one of Pilate's ancestors was a freedman.

[31] According to the cursus honorum established by Augustus for office holders of equestrian rank, Pilate would have had a military command before becoming prefect of Judaea; historian Alexander Demandt speculates that this could have been with a legion stationed at the Rhine or Danube.

[35] As Tiberius had retired to the island of Capri in 26, scholars such as E. Stauffer have argued that Pilate may have actually been appointed by the powerful Praetorian Prefect Sejanus, who was executed for treason in 31.

[77] Discussing the paucity of extra-biblical mentions of the crucifixion, Alexander Demandt argues that the execution of Jesus was probably not seen as a particularly important event by the Romans, as many other people were crucified at the time and forgotten.

[81] Pilate may have judged Jesus according to the cognitio extra ordinem, a form of trial for capital punishment used in the Roman provinces and applied to non-Roman citizens that provided the prefect with greater flexibility in handling the case.

Brown also rejects the historicity of Pilate washing his hands and of the blood curse, arguing that these narratives, which only appear in the Gospel of Matthew, reflect later contrasts between the Jews and Jewish Christians.

[7][91] Warren Carter argues that Pilate is portrayed as skillful, competent, and manipulative of the crowd in Mark, Matthew, and John, only finding Jesus innocent and executing him under pressure in Luke.

[98] J. P. Lémonon argues that the fact that Pilate was not reinstated by Caligula does not mean that his trial went badly, but may simply have been because after ten years in the position it was time for him to take a new posting.

[103] Maier argues that "[i]n all probability, then, the fate of Pontius Pilate lay clearly in the direction of a retired government official, a pensioned Roman ex-magistrate, than in anything more disastrous.

[116] The inscription read as follows: The only clear items of text are the names "Pilate" and the title quattuorvir ("IIII VIR"), a type of local city official responsible for conducting a census every five years.

[119] E. Stauffer and E. M. Smallwood argued that the coins' use of pagan symbols was deliberately meant to offend the Jews and connected changes in their design to the fall of the powerful Praetorian prefect Sejanus in 31.

[124] Joan Taylor has argued that the symbolism on the coins shows how Pilate attempted to promote the Roman imperial cult in Judaea, in spite of local Jewish and Samaritan religious sensitivities.

[141][142] Beginning in the fourth century, a large body of Christian apocryphal texts developed concerning Pilate, making up one of the largest groups of surviving New Testament Apocrypha.

[161] The Evangelium Gamalielis, possibly of medieval origin and preserved in Arabic, Coptic, and Ge'ez,[162] says Jesus was crucified by Herod, whereas Pilate was a true believer in Christ who was martyred for his faith; similarly, the Martyrium Pilati, possibly medieval and preserved in Arabic, Coptic, and Ge'ez,[162] portrays Pilate, as well as his wife and two children, as being crucified twice, once by the Jews and once by Tiberius, for his faith.

[167][168] Beginning in the eleventh century, more extensive legendary biographies of Pilate were written in Western Europe, adding details to information provided by the bible and apocrypha.

[179] The town of Tarragona in modern Spain possesses a first-century Roman tower, which, since the eighteenth-century, has been called the "Torre del Pilatos", in which Pilate is claimed to have spent his last years.

The Byzantine chronicler George Kedrenos (c. 1100) wrote that Pilate was condemned by Caligula to die by being left in the sun enclosed in the skin of a freshly slaughtered cow, together with a chicken, a snake, and a monkey.

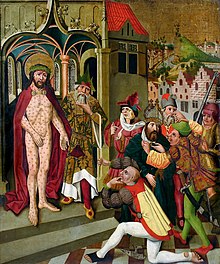

[192] The majority of depictions from this time period come from France or Germany, belonging to Carolingian or later Ottonian art,[193] and are mostly on ivory, with some in frescoes, but no longer on sculpture except in Ireland.

[209] Depictions of Pilate in this period are mostly found in private devotional settings such as on ivory or in books; he is also a major subject in a number of panel-paintings, mostly German, and frescoes, mostly Scandinavian.

by the Russian painter Nikolai Ge, which was completed in 1890; the painting was banned from exhibition in Russia in part because the figure of Pilate was identified as representing the tsarist authorities.

[241] In the Wakefield plays, Pilate is portrayed as wickedly evil, describing himself as Satan's agent (mali actoris) while plotting Christ's torture so as to extract the most pain.

[225] One of the earliest literary works in which he plays a large role is French writer Anatole France's 1892 short story "Le Procurateur de Judée" ("The Procurator of Judaea"), which portrays an elderly Pilate who has been banished to Sicily.

[260] Swiss playwright Max Frisch's comedy Die chinesische Mauer portrays Pilate as a skeptical intellectual who refuses to take responsibility for the suffering he has caused.

[271] The Pilate in the film, played by Barry Dennen, expands on John 18:38 to question Jesus on the truth and appears, in McDonough's view, as "an anxious representative of [...] moral relativism".

[274] Mel Gibson's 2004 film The Passion of the Christ portrays Pilate, played by Hristo Shopov, as a sympathetic, noble-minded character,[275] fearful that the Jewish priest Caiaphas will start an uprising if he does not give in to his demands.

[275] McDonough argues that "Shopov gives us a very subtle Pilate, one who manages to appear alarmed though not panicked before the crowd, but who betrays far greater misgivings in private conversation with his wife.

[293] According to this theory, following Sejanus's execution in 31 AD and Tiberius's purges of his supporters, Pilate, fearful of being removed himself, became far more cautious, explaining his apparently weak and vacillating attitude at the trial of Jesus.

[296] Carter notes this theory arose in the context of the aftermath of the Holocaust, that the evidence that Sejanus was anti-Semitic depends entirely on Philo, and that "[m]ost scholars have not been convinced that it is an accurate or a fair picture of Pilate.

Obverse: ΤΙΒΕΡΙΟΥ ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ surrounding lituus .

Reverse: Wreath surrounding date LIϚ (year 16, 29/30 CE). Found in Lebanon.

Reverse: Greek letters ΤΙΒΕΡΙΟΥ ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ and date LIϚ (year 16 = 29/30), surrounding simpulum .

Obverse: Greek letters ΙΟΥΛΙΑ ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ, three bound heads of barley, the outer two heads drooping.