Third Anglo-Maratha War

[citation needed] While the Marathas were fighting the Mughals in the early 18th century, the British held small trading posts in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta.

The envoys were successful, and a treaty was signed on 12 July 1739 that gave the British East India Company rights to free trade in Maratha territory.

Unable to see the rising power of the British, the Peshwa set a precedent by seeking their help to solve internal Maratha conflicts.

[note 4] The Marathas were still in a very strong position when the new Governor General of British controlled territories Cornwallis arrived in India in 1786.

Chhabra hypothesizes that even if the British technical superiority were discounted, they would have won the war because of the discipline and organization in their ranks.

[20] After the First Anglo-Maratha war, Warren Hastings declared in 1783 that the peace established with the Marathas was on such a firm ground that it was not going to be shaken for years to come.

[21] The British believed that a new permanent approach was needed to establish and maintain continuous contact with the Peshwa's court in Pune.

[22] Efforts to modernize the armies were half-hearted and undisciplined: newer techniques were not absorbed by the soldiers, while the older methods and experience were outdated and obsolete.

Foreign officers were responsible for the handling of the imported guns; the Marathas never used their own men in considerable numbers for the purpose.

Although Maratha infantry was praised by the likes of Wellington, they were poorly led by their generals and heavily relied on Arab and Pindari mercenaries.

[28] On 19 October 1817, Baji Rao II celebrated the Dassera festival in Pune, where troops were assembled in large numbers.

[25] During the celebrations, a large flank of the Maratha cavalry pretended they were charging towards the British sepoys but wheeled off at the last minute.

This display was intended as a slight towards Elphinstone [30] and as a scare tactic to prompt the defection and recruitment of British sepoys to the Peshwa's side.

[37] This included over 60 battalions of Native Infantry, multiple battalions derived from British regiments, numerous sections of cavalry and dragoons, in addition to artillery, horse artillery and rocket troops, all armed with the most modern weapons and equipped with highly organised supply lines.

[38] The war began as a campaign against the Pindaris,[39] but the first battle occurred at Pune where the Peshwa, Baji Rao II, attacked the under-strength British cantonment on 5 November 1817.

Although Baji Rao's commander Trimabkji killed Lieutenant Chishom, the Marathas were forced to evacuate the village and retreated during the night.

[44] After the battle the British forces under general Pritzler[44] pursued the Peshwa, who fled southwards towards Karnataka with the Raja of Satara.

[45][46] Not receiving support from the Raja of Mysore, the Peshwa doubled back and passed General Pritzler to head towards Solapur.

Whenever Baji Rao was pressed by the British, Gokhale and his light troops hovered around the Peshwa and fired long shots.

"[49][note 6] On 3 June 1818 Baji Rao surrendered to the British and negotiated the sum of ₹ eight lakhs as annual maintenance.

[51] Baji Rao obtained promises from the British in favour of the Jagirdars, his family, the Brahmins, and religious institutions.

[54] The Pindaris frequently raided villages in Central India and it was thought that this region was being rapidly reduced to the condition of a desert because the peasants were unable to support themselves on the land.

General Hislop from the Madras Residency attacked the Pindaris from the south and drove them beyond the Narmada river, where governor-general Francis Rawdon-Hastings was waiting with his army.

[57] With the principal routes from Central India being occupied by British detachments, the Pindari forces were completely broken up, scattered in the course of a single campaign.

Being armed only with spears, they made no stand against the regular troops, and even in small bands they were unable to escape the ring of forces drawn around them.

As it was now clear that a battle was in the offing, Jenkins asked for reinforcements from nearby British East India Company troops.

[67] The Marathas, fighting with the Arabs, made good initial gains by charging up the hill and forcing the British to retreat to the south.

The 1,200-strong garrison was subject to constant artillery bombardments before the British launched an assault, which led to the fort's capture on 9 April.

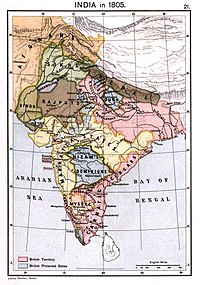

[82] The British acquired large chunks of territory from the Maratha Empire and in effect put an end to their most dynamic opposition.

[85] After 1818, Mountstuart Elphinstone reorganized the administrative divisions for revenue collection,[86] thus reducing the importance of the Patil, the Deshmukh, and the Deshpande.