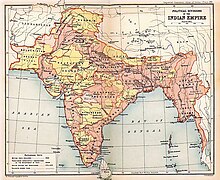

Political integration of India

In 1920, Congress (party) under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi declared swaraj (self-rule) for Indians as its goal and asked the princes of India to establish responsible government.

[2] In the same year, Gandhi played a major role in proposing a federation involving a union between British India and the princely states, with an Indian central government.

[19] Early British plans for the transfer of power, such as the offer produced by the Cripps Mission, recognised the possibility that some princely states might choose to stand out of independent India.

[53] At the time, several princes complained that they were being betrayed by Britain, who they regarded as an ally,[54] and Sir Conrad Corfield resigned his position as head of the Political Department in protest at Mountbatten's policies.

[56] Modern historians such as E. W. R. Lumby and R. J. Moore, however, take the view that Mountbatten played a crucial role in ensuring that the princely states agreed to accede to India.

Rulers who agreed to accede would receive guarantees that their extra-territorial rights, such as immunity from prosecution in Indian courts and exemption from customs duty, would be protected, that they would be allowed to democratise slowly, that none of the eighteen major states would be forced to merge, and that they would remain eligible for British honours and decorations.

[69] The limited scope of the Instruments of Accession and the promise of a wide-ranging autonomy and the other guarantees they offered, gave sufficient comfort to many rulers, who saw this as the best deal they could strike given the lack of support from the British, and popular internal pressures.

Simultaneously, they cut off supplies of fuel and coal to Junagadh, severed air and postal links, sent troops to the frontier, and reoccupied the principalities of Mangrol and Babariawad that had acceded to India.

[85] Indian troops secured Jammu, Srinagar and the valley itself during the First Kashmir War, but the intense fighting flagged with the onset of winter, which made much of the state impassable.

Prime Minister Nehru, recognising the degree of international attention brought to bear on the dispute, sought UN arbitration, arguing that India would otherwise have to invade Pakistan itself, in view of its failure to stop the tribal incursions.

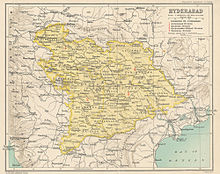

[99] On 13 September 1948, two days after the death of Jinnah, the Indian Army was sent into Hyderabad under Operation Polo on the grounds that the law and order situation there threatened the peace of South India.

[104] He thereupon disavowed the complaints that had been made to the UN and, despite vehement protests from Pakistan and strong criticism from other countries, the Security Council did not deal further with the question, and Hyderabad was absorbed into India.

[105] The Instruments of Accession were limited, transferring control of only three matters to India, and would by themselves have produced a rather loose federation, with significant differences in administration and governance across the various states.

[111][failed verification] Patel and Menon emphasised that without integration, the economies of states would collapse, and anarchy would arise if the princes were unable to provide democracy and govern properly.

[111][failed verification] Given that the merger involved the breach of guarantees personally given by Mountbatten, initially, Patel and Nehru intended to wait until after his term as Governor-General ended.

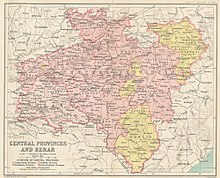

Bhopal, whose ruler was proud of the efficiency of his administration and feared that it would lose its identity if merged with the Maratha states that were its neighbours, also became a directly administered Chief Commissioner's Province, as did Bilaspur, much of which was likely to be flooded on completion of the Bhakra dam.

The States Department accepted his suggestion, and implemented it through a special covenant signed by the rajpramukhs of the merged princely unions, binding them to act as constitutional monarchs.

A referendum in Pondicherry and Karaikal in October 1954 resulted in a vote in favour of merger, and on 1 November 1954, de facto control over all four enclaves was transferred to the Republic of India.

[138] In December 1960, the United Nations General Assembly rejected Portugal's contention that its overseas possessions were provinces, and formally listed them as "non-self-governing territories".

[141] Although Nehru continued to favour a negotiated solution, the Portuguese suppression of a revolt in Angola in 1961 radicalised Indian public opinion, and increased the pressure on the Government of India to take military action.

[148] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal, supported by the minority Bhutia and Lepcha upper classes, attempted to negotiate greater powers, particularly over external affairs, to give Sikkim more of an international personality.

Kashmir, uniquely amongst princely states, was not required to sign either a Merger Agreement or a revised Instrument of Accession giving India control over a larger number of issues than the three originally provided for.

[154] Similarly, Ganguly suggests that the policies of the Indian government towards Kashmir meant that the state, unlike other parts of India, never developed the solid political institutions associated with a modern multi-ethnic democracy.

[155] As a result, the growing dissatisfaction with the status quo felt by an increasingly politically aware youth was expressed through non-political channels[156] which Pakistan, seeking to weaken India's hold over Kashmir, transformed into an active insurgency.

It is suggested that he wanted India to ask for a plebiscite in Junagadh and Hyderabad, knowing thus that the principle then would have to be applied to Kashmir, where the Muslim-majority would, he believed, vote for Pakistan.

[163] Although Patel's opinions were not India's policy, nor were they shared by Nehru, both leaders were angered at Jinnah's courting the princes of Jodhpur, Bhopal and Indore, leading them to take a harder stance on a possible deal with Pakistan.

Ian Copland argues that the Congress leaders did not intend the settlement contained in the Instruments of Accession to be permanent even when they were signed, and at all times privately contemplated a complete integration of the sort that ensued between 1948 and 1950.

[166] He also criticises Mountbatten's role, saying that while he stayed within the letter of the law, he was at least under a moral obligation to do something for the princes when it became apparent that the Government of India was going to alter the terms on which accession took place, and that he should never have lent his support to the bargain given that it could not be guaranteed after independence.

[167] Both Copland and Ramusack argue that, in the ultimate analysis, one of the reasons why the princes consented to the demise of their states was that they felt abandoned by the British, and saw themselves as having little other option.

[168] Older historians such as Lumby, in contrast, take the view that the princely states could not have survived as independent entities after the transfer of power, and that their demise was inevitable.