Euclidean plane

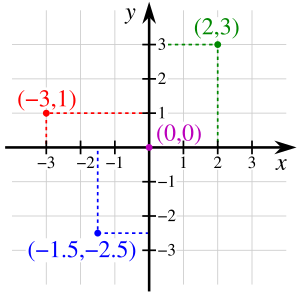

It is a geometric space in which two real numbers are required to determine the position of each point.

It has also metrical properties induced by a distance, which allows to define circles, and angle measurement.

Books I through IV and VI of Euclid's Elements dealt with two-dimensional geometry, developing such notions as similarity of shapes, the Pythagorean theorem (Proposition 47), equality of angles and areas, parallelism, the sum of the angles in a triangle, and the three cases in which triangles are "equal" (have the same area), among many other topics.

The coordinates can also be defined as the positions of the perpendicular projections of the point onto the two axes, expressed as signed distances from the origin.

[2] The concept of using a pair of fixed axes was introduced later, after Descartes' La Géométrie was translated into Latin in 1649 by Frans van Schooten and his students.

These commentators introduced several concepts while trying to clarify the ideas contained in Descartes' work.

These are named after Jean-Robert Argand (1768–1822), although they were first described by Danish-Norwegian land surveyor and mathematician Caspar Wessel (1745–1818).

[4] Argand diagrams are frequently used to plot the positions of the poles and zeroes of a function in the complex plane.

In Euclidean geometry, a plane is a flat two-dimensional surface that extends indefinitely.

A prototypical example is one of a room's walls, infinitely extended and assumed infinitesimal thin.

There exist infinitely many non-convex regular polytopes in two dimensions, whose Schläfli symbols consist of rational numbers {n/m}.

In general, for any natural number n, there are n-pointed non-convex regular polygonal stars with Schläfli symbols {n/m} for all m such that m < n/2 (strictly speaking {n/m} = {n/(n − m)}) and m and n are coprime.

There are an infinitude of other curved shapes in two dimensions, notably including the conic sections: the ellipse, the parabola, and the hyperbola.

Another mathematical way of viewing two-dimensional space is found in linear algebra, where the idea of independence is crucial.

In this viewpoint, the dot product of two Euclidean vectors A and B is defined by[6] where θ is the angle between A and B.

In a rectangular coordinate system, the gradient is given by For some scalar field f : U ⊆ R2 → R, the line integral along a piecewise smooth curve C ⊂ U is defined as where r: [a, b] → C is an arbitrary bijective parametrization of the curve C such that r(a) and r(b) give the endpoints of C and

Let C be a positively oriented, piecewise smooth, simple closed curve in a plane, and let D be the region bounded by C. If L and M are functions of (x, y) defined on an open region containing D and have continuous partial derivatives there, then[7][8] where the path of integration along C is counterclockwise.