Plasma display

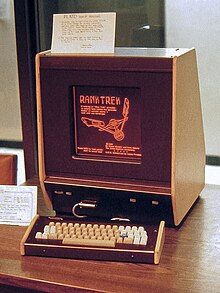

[7] The first practical plasma video display was co-invented in 1964 at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign by Donald Bitzer, H. Gene Slottow, and graduate student Robert Willson for the PLATO computer system.

[10] The original neon orange monochrome Digivue display panels built by glass producer Owens-Illinois were very popular in the early 1970s because they were rugged and needed neither memory nor circuitry to refresh the images.

[12] Nevertheless, the plasma displays' relatively large screen size and 1 inch (25.4 mm) thickness made them suitable for high-profile placement in lobbies and stock exchanges.

They became popular for their bright orange luminous look and found nearly ubiquitous use throughout the late 1970s and into the 1990s in cash registers, calculators, pinball machines, aircraft avionics such as radios, navigational instruments, and stormscopes; test equipment such as frequency counters and multimeters; and generally anything that previously used nixie tube or numitron displays with a high digit-count.

These displays were eventually replaced by LEDs because of their low current-draw and module-flexibility, but are still found in some applications where their high brightness is desired, such as pinball machines and avionics.

[14] Due to heavy competition from monochrome LCDs used in laptops and the high costs of plasma display technology, in 1987 IBM planned to shut down its factory in Kingston, New York, the largest plasma plant in the world, in favor of manufacturing mainframe computers, which would have left development to Japanese companies.

[16] Dr. Larry F. Weber, a University of Illinois ECE PhD (in plasma display research) and staff scientist working at CERL (home of the PLATO System), co-founded Plasmaco with Stephen Globus and IBM plant manager James Kehoe, and bought the plant from IBM for US$50,000.

More decisively, LCDs offered higher resolutions and true 1080p support, while plasmas were stuck at 720p, which made up for the price difference.

[33] When the sales figures for the 2007 Christmas season were finally tallied, analysts were surprised to find that not only had LCD outsold plasma, but CRTs as well, during the same period.

The February 2009 announcement that Pioneer Electronics was ending production of plasma screens was widely considered the tipping point in the technology's history as well.

This decline has been attributed to the competition from liquid crystal (LCD) televisions, whose prices have fallen more rapidly than those of the plasma TVs.

These compartments, or "bulbs" or "cells", hold a mixture of noble gases and a minuscule amount of another gas (e.g., mercury vapor).

[45][46] Control circuitry charges the electrodes that cross paths at a cell, creating a voltage difference between front and back.

[10] Plasma panels may be built without nitrogen gas, using xenon, neon, argon, and helium instead with mercury being used in some early displays.

Plasma panels use pulse-width modulation (PWM) to control brightness: by varying the pulses of current flowing through the different cells thousands of times per second, the control system can increase or decrease the intensity of each subpixel color to create billions of different combinations of red, green and blue.

They had a very low luminance "dark-room" black level compared with the lighter grey of the unilluminated parts of an LCD screen.

[63][64][65][66] Plasma displays have superior uniformity to LCD panel backlights, which nearly always produce uneven brightness levels, although this is not always noticeable.

[69] On the surface, this is a significant advantage of plasma over most other current display technologies, a notable exception being organic light-emitting diode.

Although there are no industry-wide guidelines for reporting contrast ratio, most manufacturers follow either the ANSI standard or perform a full-on-full-off test.

The ANSI standard uses a checkered test pattern whereby the darkest blacks and the lightest whites are simultaneously measured, yielding the most accurate "real-world" ratings.

[73][74][75] This precharging means the cells cannot achieve a true black,[76] whereas an LED backlit LCD panel can actually turn off parts of the backlight, in "spots" or "patches" (this technique, however, does not prevent the large accumulated passive light of adjacent lamps, and the reflection media, from returning values from within the panel).

With an LCD, black pixels are generated by a light polarization method; many panels are unable to completely block the underlying backlight.

More recent LCD panels using LED illumination can automatically reduce the backlighting on darker scenes, though this method cannot be used in high-contrast scenes, leaving some light showing from black parts of an image with bright parts, such as (at the extreme) a solid black screen with one fine intense bright line.

[63][64][77] Earlier generation displays (circa 2006 and prior) had phosphors that lost luminosity over time, resulting in gradual decline of absolute image brightness.

Early plasma televisions were plagued by burn-in, making it impossible to use video games or anything else that displayed static images.

However, unlike burn-in, this charge build-up is transient and self-corrects after the image condition that caused the effect has been removed and a long enough period has passed (with the display either off or on).

Plasma manufacturers have tried various ways of reducing burn-in such as using gray pillarboxes, pixel orbiters and image washing routines.

Recent models have a pixel orbiter that moves the entire picture slower than is noticeable to the human eye, which reduces the effect of burn-in but does not prevent it.

As a result, picture quality varies depending on the performance of the video scaling processor and the upscaling and downscaling algorithms used by each display manufacturer.

Early high-definition (HD) plasma displays had a resolution of 1024x1024 and were alternate lighting of surfaces (ALiS) panels made by Fujitsu and Hitachi.