Plasma (physics)

Plasma (from Ancient Greek πλάσμα (plásma) 'moldable substance'[1]) is one of four fundamental states of matter (the other three being solid, liquid, and gas) characterized by the presence of a significant portion of charged particles in any combination of ions or electrons.

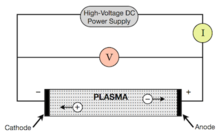

[2][3][4][5] Plasma can be artificially generated, for example, by heating a neutral gas or subjecting it to a strong electromagnetic field.

[8] Depending on temperature and density, a certain number of neutral particles may also be present, in which case plasma is called partially ionized.

[10] Whether a given degree of ionization suffices to call a substance "plasma" depends on the specific phenomenon being considered.

Crookes presented a lecture on what he called "radiant matter" to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, in Sheffield, on Friday, 22 August 1879.

[13][14] Mott-Smith recalls, in particular, that the transport of electrons from thermionic filaments reminded Langmuir of "the way blood plasma carries red and white corpuscles and germs.

The following table summarizes some principal differences: Three factors define an ideal plasma:[24][25] The strength and range of the electric force and the good conductivity of plasmas usually ensure that the densities of positive and negative charges in any sizeable region are equal ("quasineutrality").

Examples are charged particle beams, an electron cloud in a Penning trap and positron plasmas.

At low temperatures, ions and electrons tend to recombine into bound states—atoms[33]—and the plasma will eventually become a gas.

In most cases, the electrons and heavy plasma particles (ions and neutral atoms) separately have a relatively well-defined temperature; that is, their energy distribution function is close to a Maxwellian even in the presence of strong electric or magnetic fields.

This is especially common in weakly ionized technological plasmas, where the ions are often near the ambient temperature while electrons reach thousands of kelvin.

In the special case that double layers are formed, the charge separation can extend some tens of Debye lengths.

[37] The magnitude of the potentials and electric fields must be determined by means other than simply finding the net charge density.

The density of a non-neutral plasma must generally be very low, or it must be very small, otherwise, it will be dissipated by the repulsive electrostatic force.

A common quantitative criterion is that a particle on average completes at least one gyration around the magnetic-field line before making a collision, i.e.,

Because fluid models usually describe the plasma in terms of a single flow at a certain temperature at each spatial location, they can neither capture velocity space structures like beams or double layers, nor resolve wave-particle effects.

The other, known as the particle-in-cell (PIC) technique, includes kinetic information by following the trajectories of a large number of individual particles.

The Vlasov equation may be used to describe the dynamics of a system of charged particles interacting with an electromagnetic field.

In magnetized plasmas, a gyrokinetic approach can substantially reduce the computational expense of a fully kinetic simulation.

[50] Electrical resistance along the arc creates heat, which dissociates more gas molecules and ionizes the resulting atoms.

Therefore, the electrical energy is given to electrons, which, due to their great mobility and large numbers, are able to disperse it rapidly by elastic collisions to the heavy particles.

[51] Plasmas find applications in many fields of research, technology and industry, for example, in industrial and extractive metallurgy,[51][52] surface treatments such as plasma spraying (coating), etching in microelectronics,[53] metal cutting[54] and welding; as well as in everyday vehicle exhaust cleanup and fluorescent/luminescent lamps,[48] fuel ignition, and even in supersonic combustion engines for aerospace engineering.

[55] A world effort was triggered in the 1960s to study magnetohydrodynamic converters in order to bring MHD power conversion to market with commercial power plants of a new kind, converting the kinetic energy of a high velocity plasma into electricity with no moving parts at a high efficiency.

Research was also conducted in the field of supersonic and hypersonic aerodynamics to study plasma interaction with magnetic fields to eventually achieve passive and even active flow control around vehicles or projectiles, in order to soften and mitigate shock waves, lower thermal transfer and reduce drag.

When used in combination with a high Hall parameter, a critical value triggers the problematic electrothermal instability which limited these technological developments.

Such systems lie in some sense on the boundary between ordered and disordered behaviour and cannot typically be described either by simple, smooth, mathematical functions, or by pure randomness.

The spontaneous formation of interesting spatial features on a wide range of length scales is one manifestation of plasma complexity.

[73] One interesting aspect of the filamentation generated plasma is the relatively low ion density due to defocusing effects of the ionized electrons.

[75] However, later it was found that the external magnetic fields in this configuration could induce kink instabilities in the plasma and subsequently lead to an unexpectedly high heat loss to the walls.

[76] In 2013, a group of materials scientists reported that they have successfully generated stable impermeable plasma with no magnetic confinement using only an ultrahigh-pressure blanket of cold gas.