Plasma actuator

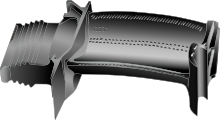

Dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma actuators are widely utilized in airflow control applications.

The performance of plasma actuators is determined by dielectric materials and power inputs, later is limited by the qualities of MOSFET or IGBT.

Locating the initial encapsulated electrode closer to the dielectric surface results in induced velocities higher than the baseline case for a given voltage.

[11] The surface temperature plays an important role in limiting the usefulness of a dielectric barrier discharge plasma actuator.

It is found that for a constant peak-to-peak voltage the maximum velocity produced by the actuator depends directly on the dielectric surface temperature.

The findings suggest that by changing the actuator temperature the performance can be maintained or even altered at different environmental conditions.

[13] [14] Although plasma actuators have been extensively characterized for their performance as flow control devices, the notion that they might fail under adverse conditions such as dew, drizzle or dust makes them less popular in practical applications.

[18][19] A recent publication has simulated light rain by directly spraying water droplets on to a working plasma actuator and showed its effect on thrust recovery as the performance metric.

A plasma actuator induces a local flow speed perturbation, which will be developed downstream to a vortex sheet.

The difference between this and traditional vortex generation is that there are no mechanical moving parts or any drilling holes on aerodynamic surfaces, demonstrating an important benefit of plasma actuators.

[28] Recent work showed significant turbulent drag reduction by modifying energetic modes of transitional flow using these actuators.

Interest in plasma actuators as active flow control devices is growing rapidly due to their lack of mechanical parts, light weight and high response frequency.

The characteristics of a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma actuator when exposed to an unsteady flow generated by a shock tube is examined.

The cumbersome design and maintenance efforts of mechanical and hydraulic transmission systems in a classical rudder can thus be saved.

The reason is that bang-bang control is time optimal and insensitive to plasma actuations, which quickly vary in difference atmospheric and electric conditions.

In those applications, one of the most common techniques used is film cooling where a secondary fluid such as air or another coolant is introduced to a surface in a high temperature environment.

A modern closed-loop control system and the following information theoretical methods can be applied to the relatively classical aerodynamic sciences.