Plasticity (physics)

[1][2] For example, a solid piece of metal being bent or pounded into a new shape displays plasticity as permanent changes occur within the material itself.

In cellular materials such as liquid foams or biological tissues, plasticity is mainly a consequence of bubble or cell rearrangements, notably T1 processes.

Twinning is the plastic deformation which takes place along two planes due to a set of forces applied to a given metal piece.

On the nanoscale the primary plastic deformation in simple face-centered cubic metals is reversible, as long as there is no material transport in form of cross-slip.

[7] Shape-memory alloys such as Nitinol wire also exhibit a reversible form of plasticity which is more properly called pseudoelasticity.

Since amorphous materials, like polymers, are not well-ordered, they contain a large amount of free volume, or wasted space.

This haziness is the result of crazing, where fibrils are formed within the material in regions of high hydrostatic stress.

The foams can be made of any material with a plastic yield point which includes rigid polymers and metals.

The causes of plasticity in soils can be quite complex and are strongly dependent on the microstructure, chemical composition, and water content.

Inelastic deformations of rocks and concrete are primarily caused by the formation of microcracks and sliding motions relative to these cracks.

At high temperatures and pressures, plastic behavior can also be affected by the motion of dislocations in individual grains in the microstructure.

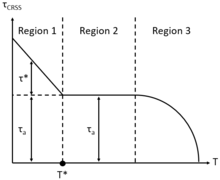

[9] Time-independent plastic flow in both single crystals and polycrystals is defined by a critical/maximum resolved shear stress (τCRSS), initiating dislocation migration along parallel slip planes of a single slip system, thereby defining the transition from elastic to plastic deformation behavior in crystalline materials.

At T = T*, the moderate temperature region 2 (0.25Tm < T < 0.7Tm) is defined, where the thermal shear stress component τ* → 0, representing the elimination of point defect impedance to dislocation migration.

Notably, in region 2 moderate temperature time-dependent plastic deformation (creep) mechanisms such as solute-drag should be considered.

Furthermore, in the high temperature region 3 (T ≥ 0.7Tm) έ can be low, contributing to low τCRSS, however plastic flow will still occur due to thermally activated high temperature time-dependent plastic deformation mechanisms such as Nabarro–Herring (NH) and Coble diffusional flow through the lattice and along the single crystal surfaces, respectively, as well as dislocation climb-glide creep.

During the linear hardening stage 2 of flow, the work hardening rate becomes high as considerable stress is required to overcome the stress field interactions of dislocations migrating on non-parallel slip planes (i.e. multiple slip systems), acting as strong obstacles to flow.

Plasticity in polycrystals differs substantially from that in single crystals due to the presence of grain boundary (GB) planar defects, which act as very strong obstacles to plastic flow by impeding dislocation migration along the entire length of the activated slip plane(s).

The GB constraint for polycrystals can be explained by considering a grain boundary in the xz plane between two single crystals A and B of identical composition, structure, and slip systems, but misoriented with respect to each other.

Hence, for a given composition and structure, a single crystal with less than five independent slip systems is stronger (exhibiting a greater extent of plasticity) than its polycrystalline form.

Paramount is the fact that macroscopic yielding of the bicrystal is prolonged until the higher value of τCRSS between grains A and B is achieved, according to the GB constraint.

Thus, for a given composition and structure, a polycrystal with five independent slip systems is stronger (greater extent of plasticity) than its single crystalline form.

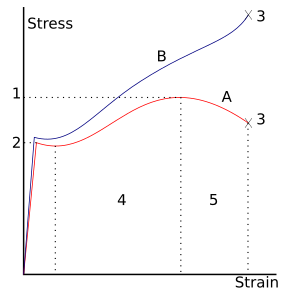

However, even ductile metals will fracture when the strain becomes large enough—this is as a result of work hardening of the material, which causes it to become brittle.

In 1934, Egon Orowan, Michael Polanyi and Geoffrey Ingram Taylor, roughly simultaneously, realized that the plastic deformation of ductile materials could be explained in terms of the theory of dislocations.

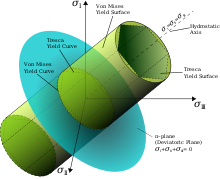

If the stress exceeds a critical value, as was mentioned above, the material will undergo plastic, or irreversible, deformation.

The Tresca criterion is based on the notion that when a material fails, it does so in shear, which is a relatively good assumption when considering metals.

- Ultimate strength

- Yield strength (yield point)

- Rupture

- Strain hardening region

- Necking region

- Apparent stress ( F / A 0 )

- Actual stress ( F / A )