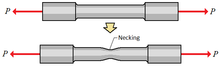

Necking (engineering)

Necking results from an instability during tensile deformation when the cross-sectional area of the sample decreases by a greater proportion than the material strain hardens.

Armand Considère published the basic criterion for necking in 1885, in the context of the stability of large scale structures such as bridges.

However, while the phenomenon is caused by the same basic effect in both materials, they tend to have different types of (true) stress-strain curve, such that they should be considered separately in terms of necking behaviour.

For example, the gradient can in some cases rise sharply with increasing strain, due to the polymer chains becoming aligned as they reorganise during plastic deformation.

Since many stress-strain curves are presented as nominal plots, and this is a simple condition that can be identified by visual inspection, it is in many ways the easiest criterion to use to establish the onset of necking.

On the other hand, the peak in a nominal stress-strain curve is commonly a fairly flat plateau, rather than a sharp maximum, so accurate assessment of the strain at the onset of necking may be difficult.

Ductile polymers often exhibit stable necks because molecular orientation provides a mechanism for hardening that predominates at large strains.