Plato's problem

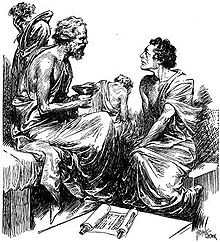

[4] Plato's problem is most clearly illustrated in the Meno dialogue, in which Socrates demonstrates that an uneducated boy nevertheless understands geometric principles.

Gaining a more precise understanding of human knowledge, whether defined as innate, experiential, or both, is an important part of effective problem solving.

In the Meno, Plato theorizes about the relationship between knowledge and experience and provides an explanation for how it is possible to know something that one has never been explicitly taught.

Plato's early philosophical endeavors involved dialogues discussing many ideas, such as the differences between knowledge and opinion, particulars and universals, and God and man.

Some claim that Plato was truly trying to discover objective reality through these mystical speculations while others maintain that the dialogues are stories to be interpreted only as parables, allegories, and emotional appeals to religious experience.

Regardless, Plato would come to formulate a more rigorous and comprehensive philosophy later in his life, one that reverberates in contemporary Western thought to this day.

Within these works are found a comprehensive philosophy that addresses epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, aesthetics, theology, and logic.

If someone disagreed with him, Socrates would execute this process in order to bring about his interlocutor's reluctant admission of inconsistencies and contradictions.

A crucial point in the dialogue is when Socrates tells Meno that there is no such thing as teaching, only recollection of knowledge from past lives, or anamnesis.

Socrates claims that he can demonstrate this by showing that one of Meno's servants, a slave boy, knows geometric principles though he is uneducated.

The crucial point to this part of the dialogue is that, though the boy has no training, he knows the correct answers to the questions – he intrinsically knows the Pythagorean proposition.

Shortly before the demonstration of Pythagoras' theorem, the dialogue takes an epistemological turn when the interlocutors begin to discuss the fundamental nature of knowledge.

As a specific example, how can a child of Asian descent (say, born of Chinese parents) be set down in the middle of Topeka, Kansas and acquire "perfect English?"

All that is needed is passive input during the critical period—defined in linguistics as that period within which a child must have necessary and sufficient exposure to human language so that language acquisition occurs; without sufficient exposure to primary linguistic data, the UG does not have the necessary input for development of an individual grammar; this period is commonly recognized as spanning from birth to adolescence, generally up to the age of 12 years, though individual variations are possible.

To address the issue of apparently limited input, one must turn to what is possibly the most quoted of all arguments in support of universal grammar and its nativist interpretation – Plato's problem.

The phrase refers to the Socratic dialogue, the Meno; Noam Chomsky is often attributed with applying the term to the study of linguistics.

[6] In The Cambridge Companion to Chomsky, David Lightfoot explains as follows: The problem arises in the domain of language acquisition in that children attain infinitely more than they experience.

So there is more, much more, to language acquisition than mimicking what we hear in childhood, and there is more to it than the simple transmission of a set of words and sentences from one generation of speakers to the next.

Specifically, the stimuli to which children are exposed during the critical period do not encompass every lawful example of grammatical structure relevant to the particular language.

As Plato suggests in the Meno dialogue, the bridge between input (whether limited or lacking) and output is innate knowledge.

There have been studies of perception and attention that support the idea that there is an abundance of knowledge available to an individual at any given moment (Blake & Sekuler, 2006).

A key ingredient to the beginning stages of perception requires the attention of the observer on some focal point or stimulus.

In other words, it is our biologically produced visual system that makes our perceptual experiences meaningful[clarification needed][how?].

Some examples from auditory perception research will be helpful in explaining the fact that our perceptual faculties naturally enhance and supplement our conscious experience.

Although people may be inattentive to a portion of their environment, when they hear specific "trigger" words, their auditory capacities are redirected to another dimension[clarification needed] of perceptual awareness.

These studies point to the fact that even though we only attend to and process limited information, we have a vast amount of knowledge at our disposal through our highly unrestricted sensory registers.

This LTM availability/accessibility dichotomy is analogous to a more contemporary explanation of Plato's doctrine of reminiscence, which postulates that an individual hedge as a result of information carried over from past lives[clarification needed].

In contemporary philosophical, linguistic, and psychological circles, it is rare to maintain an unwavering stance on either of these extremes; most fall toward the middle.

Instead, researchers point to a necessarily interactive relationship in order for thought and behavior to occur[citation needed].

The neurological structures in our brain that represent the location of LTM are also biologically pre-wired, yet environmental input is needed in order for memory to flourish.