Flatworm

The digestive cavity has only one opening for both ingestion (intake of nutrients) and egestion (removal of undigested wastes); as a result, the food can not be processed continuously.

In traditional medicinal texts, Platyhelminthes are divided into Turbellaria, which are mostly non-parasitic animals such as planarians, and three entirely parasitic groups: Cestoda, Trematoda and Monogenea; however, since the turbellarians have since been proven not to be monophyletic, this classification is now deprecated.

Because they do not have internal body cavities, Platyhelminthes were regarded as a primitive stage in the evolution of bilaterians (animals with bilateral symmetry and hence with distinct front and rear ends).

[14] The lack of circulatory and respiratory organs limits platyhelminths to sizes and shapes that enable oxygen to reach and carbon dioxide to leave all parts of their bodies by simple diffusion.

[5] The space between the skin and gut is filled with mesenchyme, also known as parenchyma, a connective tissue made of cells and reinforced by collagen fibers that act as a type of skeleton, providing attachment points for muscles.

The genus Paracatenula, whose members include tiny flatworms living in symbiosis with bacteria, is even missing a mouth and a gut.

Most are predators or scavengers, and terrestrial species are mostly nocturnal and live in shaded, humid locations, such as leaf litter or rotting wood.

[5] The freshwater species Microstomum caudatum can open its mouth almost as wide as its body is long, to swallow prey about as large as itself.

[13] Some of the larger aquatic species mate by penis fencing – a duel in which each tries to impregnate the other, and the loser adopts the female role of developing the eggs.

A similar life cycle occurs with Opisthorchis viverrini, which is found in South East Asia and can infect the liver of humans, causing Cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer).

Individual adult digeneans are of a single sex, and in some species slender females live in enclosed grooves that run along the bodies of the males, partially emerging to lay eggs.

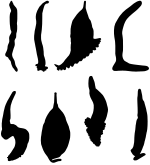

Adult monogeneans have large attachment organs at the rear, known as haptors (Greek ἅπτειν, haptein, means "catch"), which have suckers, clamps, and hooks.

In some species, the pharynx secretes enzymes to digest the host's skin, allowing the parasite to feed on blood and cellular debris.

[13] These are often called tapeworms because of their flat, slender but very long bodies – the name "cestode" is derived from the Latin word cestus, which means "tape".

[5] In the majority of species, known as eucestodes ("true tapeworms"), the neck produces a chain of segments called proglottids via a process known as strobilation.

[29][30][31] Catenulida Haplopharyngida Macrostomida Prorhynchida Polycladida Gnosonesimida Kalyptorhynchia Dalytyphloplanida Proseriata Prolecithophora Fecampiida Tricladida (planarians) Bothrioplanida (freshwater) Neodermata (flukes, tapeworms) The oldest confidently identified parasitic flatworm fossils are cestode eggs found in a Permian shark coprolite, but helminth hooks still attached to Devonian acanthodians and placoderms might also represent parasitic flatworms with simple life cycles.

[34] The "traditional" view before the 1990s was that Platyhelminthes formed the sister group to all the other bilaterians, which include, for instance, arthropods, molluscs, annelids and chordates.

[21] Other molecular phylogenetics analyses agree the redefined Platyhelminthes are most closely related to Gastrotricha, and both are part of a grouping known as Platyzoa.

[42] The earliest known fossils confidently classified as tapeworms have been dated to 270 million years ago, after being found in coprolites (fossilised faeces) from an elasmobranch.

The Carter Center estimated 200 million people in 74 countries are infected with the disease, and half the victims live in Africa.

The disease is caused by several flukes of the genus Schistosoma, which can bore through human skin; those most at risk use infected bodies of water for recreation or laundry.

[44] Infection of the digestive system by adult tapeworms causes abdominal symptoms that, whilst unpleasant, are seldom disabling or life-threatening.

[45][46] However, neurocysticercosis resulting from penetration of T. solium larvae into the central nervous system is the major cause of acquired epilepsy worldwide.

[47] In 2000, about 39 million people were infected with trematodes (flukes) that naturally parasitize fish and crustaceans, but can pass to humans who eat raw or lightly cooked seafood.

Infection of humans by the broad fish tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum occasionally causes vitamin B12 deficiency and, in severe cases, megaloblastic anemia.

[44] The threat to humans in developed countries is rising as a result of social trends: the increase in organic farming, which uses manure and sewage sludge rather than artificial fertilizers, spreads parasites both directly and via the droppings of seagulls which feed on manure and sludge; the increasing popularity of raw or lightly cooked foods; imports of meat, seafood and salad vegetables from high-risk areas; and, as an underlying cause, reduced awareness of parasites compared with other public health issues such as pollution.

Controlling parasites that infect humans and livestock has become more difficult, as many species have become resistant to drugs that used to be effective, mainly for killing juveniles in meat.

[48] There is concern in northwest Europe (including the British Isles) regarding the possible proliferation of the New Zealand planarian Arthurdendyus triangulatus and the Australian flatworm Australoplana sanguinea, both of which prey on earthworms.

[51][52] A study in Argentina shows the potential for planarians such as Girardia anceps, Mesostoma ehrenbergii, and Bothromesostoma evelinae to reduce populations of the mosquito species Aedes aegypti and Culex pipiens.

The ability of these flatworms to live in artificial containers demonstrated the potential of placing these species in popular mosquito breeding sites, which might reduce the amount of mosquito-borne disease.