Plebiscite of Veneto of 1866

The 25 July truce froze troop movements and, by that date, the entire remaining territory of the former Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia was liberated from Austrian rule, with the exclusion of only the fortresses of the Quadrilatero: Verona, Legnago, Mantua and Peschiera del Garda, as well as Palmanova and Venice, the latter city characterized by strong unitarian symbolism and the memory of its uprising during the Revolutions of 1848.

Austria, defeated by Prussia (armistice of Nikolsburg), ceded by the Peace of Prague of 23 August 1866, the remaining territories[2] of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia to France, on the understanding that Napoleon III would hand them over to Victor Emmanuel II after organizing a consultation, which formally confirmed the will of the people to the liberation of Veneto from Austrian rule.

[...] If our troops could not enter, except after the plebiscite, into Venice, if General Leboeuf had to remain there as the representative of a sovereignty, call the populations to vote etc., the country, believe it, would be put to too severe a test, the Government would be discredited, and the King would be forced to accept a situation whose consequences would not be so soon erased.The plebiscite was also opposed by the Venetian Central Committee, which in this regard cited the request of the Venetians in 1848 in favor of a merger with Piedmont of their provinces by staying under the Savoy dynasty,[5] a request renewed when the war ended in 1859.

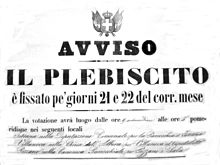

On 17 October the decree convening the plebiscite was issued and its procedures were announced: voting would take place on 21 and 22 October, while ballot counting would take place from the 23rd to the 26th; finally, on the 27th, the court of appeals in Venice, meeting in public session, would add up the data and communicate the results to the Ministry of Justice in Florence (at that time the capital of Italy), and a deputation of notables would leave to take the results to Victor Emmanuel II.

[14] News of the convocation decree, circulated in the press on Oct. 17, provoked the reaction of French plenipotentiary general Edmond Le Bœuf, who protested that “in the face of royal determinations, his handing over of Veneto to three notables so that they might organize a plebiscite becomes derisory [... ] and on the other hand, the Royal Decree being a violation of the treaty, he protested that he was reporting it to his government, and that without further order from the Emperor he would not remit Veneto.

[18] Immediately after the signing, Michiel had the tricolor raised on the flagpoles of St. Mark's Square, while volleys of artillery rang out and rumbled; later, according to the agreements made, he asked Thaon di Revel to let the Italian troops enter the city.

[10] "The President of the Council of Ministers received the following dispatch from Venice today at 10 ¾ noon:[24] The Royal Italian flag waves from the masts of St. Mark's Square, greeted by the frantic shouts of the exultant population.

The Citizens will express their will to join the Kingdom of Italy by bringing to the ballot box that will be located in the locality also to be designated either the printed bulletin or another manuscript that is valid for the manifestation of the will.

[36] The Austrian Empire, in fact, after the Treaty of Campo Formio had annulled the legal,[37] linguistic and fiscal autonomy once granted by the Serenissima to the Slovenian community, which also for this reason adhered to the Risorgimento ideas,[38] which increasingly expanded after the brief interlude of 1848.

[39] The passage to the Kingdom of Italy brought many economic, social and cultural changes for that territory,[40] but it also initiated a policy of Italianization of the Natisone and Torre Valleys,[41] which in the decades following the plebiscite fueled a progressive feeling of disappointment in the hopes of recognition of Slovenian identity.

The applauding people accompanied them along the street, and from their windows they waved their flags in exultation.Although not required (as suffrage was only for men at the time), women in Venice, Padua, Dolo, Mirano and Rovigo also wanted to cast their votes.

[45] Venetian women sent a message to the king: Men believed themselves to be wise and just, when they decreed that the one, whom they here call the most exalted part of mankind, should be excluded from participating with her action in all that pertains to the government of the public affairs.

The women of Venice do not arrogate to themselves the right of judging such a law, but they proclaim in the face of the world that never did their sex feel its bitterness and humiliation more deeply than in this circumstance, in which the people are called upon to declare whether they wish to unite with the common fatherland under the glorious scepter of Your Majesty and His august successors.

Accept therefore, O magnanimous Sire, this cry that spontaneously, unanimously, ardently bursts forth from the depths of our hearts: - Yes: we want, as do our brothers, the union of Venice with Italy under the scepter of Victor Emmanuel and his successors!In the press of the time, the patriotic nature of this participation was emphasized, neglecting the hints of protest (bitterness and humiliation) and women's claim to the right to vote.

Depositing a no was, besides being useless, the same as voting for anarchy; everyone deposited the yes.Spirito Folletto on 8 November 1866 published a series of cartoons depicting examples of plebiscite voters:[55] On 22 April 1859, due to the advance of the Piedmontese in the Milanese area, the Austrians decided to transfer to Vienna the iron crown, an ancient and precious symbol used since the Middle Ages for the coronation of the kings of Italy, which was kept at the Treasury of the Cathedral of Monza.

[56] The restitution of the crown to Italy was the subject of specific notes attached to the peace agreement,[57][58] and was officially handed over on 12 October 1866 by Austrian General Alexander von Mensdorff to the Italian representative General Menabrea; the latter, after the treaty was signed, returned from Vienna carrying the crown to Turin, and during the trip stopped in Venice and showed it to Royal Military Commissioner Thaon di Revel.

At midnight on 2 November the Venetian delegation left Venice on a special train, which, after a stop of several hours in Milan (where the Venetian representatives were festively welcomed by the Milanese municipal administration)[62] arrived at Turin station the next day, Saturday 3 November at 2 p.m., greeted by festive cannon shots[63] and received by the Turin city council and conducted through a sumptuous procession[64] to the Europa Hotel, from whose balcony Commander Tecchio delivered an address to the crowd below.

Giambattista Giustinian delivered the official speech: Sire, the event that recently took place in the Venetian Provinces and those of Mantua, and of which we are honored today to present you with the splendid result, will be remembered by later generations ...

Those 647,246 yeses, collected in the ballot boxes of our Provinces and of so many other parts where by chance there were Venetians ... offer to all Europe a novel testimony to Italian concord ...[66]To which the king replied with these words: Gentlemen, today is the most beautiful day of my life.

[70] Victor Emmanuel II arrived by royal train at Venezia Santa Lucia railway station at around 11:00 a.m., preceded by blank cannon shots fired from Fort Marghera.

The city was festively decorated, with tricolored cockades and posters of greetings (among which some, printed by a certain Simonetti, bore the anagram “Victor Emmanuel - O King, do you love Veneto?

[71] The festivities continued uninterruptedly for six days, with gala performances at the Teatro La Fenice, fireworks, masquerade balls, gas illuminations and serenades.

[72] Beginning in the mid-1990s,[73] some historians, mostly related to the Veneto regionalist movement,[74][75] began to challenge the validity of the plebiscite by imputing strong political pressure, a series of alleged frauds, and improper conduct of the voting to the Savoys,[76] adding that nineteenth-century Venetian society was predominantly rural with a still high illiteracy rate and large strata of the population were ready to accept the directions of the “upper classes.” Other historians and constitutionalists reject this anti-Risorgimento reconstruction,[77] pointing out on the one hand that the plebiscite was only a validation of the diplomatic activity following the Peace of Prague, and on the other hand pointing out the great festive atmosphere that accompanied the vote and lasted until the triumphal entry of Victor Emmanuel II into Venice on 7 November 1866, therefore ruling out altogether that the annexation was not desired by the people of Veneto and Mantua.

On the night of 8-9 May 1997 a group of people calling themselves the “Veneta Serenissima Armata” (better known as the Serenissimi) militarily occupied the bell tower of St. Mark's in Venice: these activists, who were later arrested and convicted, claimed to have done historical research and discovered elements that, in their opinion, would have invalidated, among other things, the plebiscite ratifying the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866,[78] characterized, again according to them, by alleged fraud and violations of international agreements signed during the Armistice of Cormons and the Treaty of Vienna.