Venetian language

It is sometimes spoken and often well understood outside Veneto: in Trentino, Friuli, the Julian March, Istria, and some towns of Slovenia, Dalmatia (Croatia) and Bay of Kotor (Montenegro)[13][14] by a surviving autochthonous Venetian population, and in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, the United States and the United Kingdom by Venetians in the diaspora.

The language enjoyed substantial prestige in the days of the Republic of Venice, when it attained the status of a lingua franca in the Mediterranean Sea.

Internal migrations during the 20th century also saw many Venetian-speakers settle in other regions of Italy, especially in the Pontine Marshes of southern Lazio where they populated new towns such as Latina, Aprilia and Pomezia, forming there the so-called "Venetian-Pontine" community (comunità venetopontine).

Some firms have chosen to use Venetian language in advertising, as a beer did some years ago[clarification needed] (Xe foresto solo el nome, 'only the name is foreign').

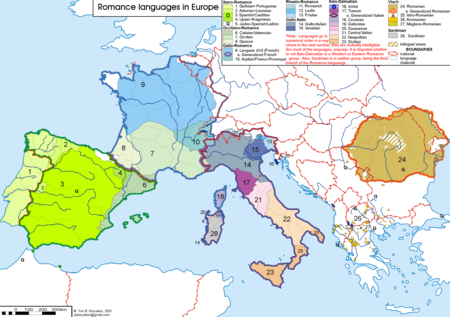

Venetian is spoken mainly in the Italian regions of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and in both Slovenia and Croatia (Istria, Dalmatia and the Kvarner Gulf).

[citation needed] Smaller communities are found in Lombardy (Mantua), Trentino, Emilia-Romagna (Rimini and Forlì), Sardinia (Arborea, Terralba, Fertilia), Lazio (Pontine Marshes), Tuscany (Grossetan Maremma)[27] and formerly in Romania (Tulcea).

In 2009, the Brazilian city of Serafina Corrêa, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, gave Talian a joint official status alongside Portuguese.

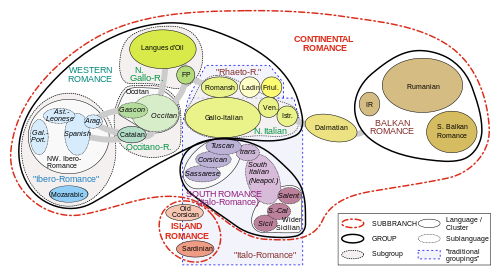

On the other hand, Venetian does share many other traits with its surrounding Gallo-Italic languages, like interrogative clitics, mandatory unstressed subject pronouns (with some exceptions), the "to be behind to" verbal construction to express the continuous aspect ("El ze drio manjar" = He is eating, lit.

The main regional varieties and subvarieties of Venetian language: All these variants are mutually intelligible, with a minimum 92% in common among the most diverging ones (Central and Western).

[citation needed] Other noteworthy variants are: Like most Romance languages, Venetian has mostly abandoned the Latin case system, in favor of prepositions and a more rigid subject–verb–object sentence structure.

[37] Very few Venetic words seem to have survived in present Venetian, but there may be more traces left in the morphology, such as the morpheme -esto/asto/isto for the past participle, which can be found in Venetic inscriptions from about 500 BC: A peculiarity of Venetian grammar is a "semi-analytical" verbal flexion, with a compulsory clitic subject pronoun before the verb in many sentences, echoing the subject as an ending or a weak pronoun.

This feature may have arisen as a compensation for the fact that the 2nd- and 3rd-person inflections for most verbs, which are still distinct in Italian and many other Romance languages, are identical in Venetian.

The function of clitics is particularly visible in long sentences, which do not always have clear intonational breaks to easily tell apart vocative and imperative in sharp commands from exclamations with "shouted indicative".

For instance, in Venetian the clitic el marks the indicative verb and its masculine singular subject, otherwise there is an imperative preceded by a vocative.

Venetian also has a special interrogative verbal flexion used for direct questions, which also incorporates a redundant pronoun: Reflexive tenses use the auxiliary verb avér ("to have"), as in English, the North Germanic languages, Catalan, Spanish, Romanian and Neapolitan; instead of èssar ("to be"), which would be normal in Italian.

The past participle is invariable, unlike Italian: Another peculiarity of the language is the use of the phrase eser drìo (literally, "to be behind") to indicate continuing action: Another progressive form in some Venetian dialects uses the construction èsar łà che (lit.

Some dialects of Venetian have certain sounds not present in Italian, such as the interdental voiceless fricative [θ], often spelled with ⟨ç⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨zh⟩, or ⟨ž⟩, and similar to English th in thing and thought.

This sound occurs, for example, in çéna ("supper", also written zhena, žena), which is pronounced the same as Castilian Spanish cena (which has the same meaning).

The voiceless interdental fricative occurs in Bellunese, north-Trevisan, and in some Central Venetian rural areas around Padua, Vicenza and the mouth of the river Po.

In dialects having a null realization of intervocalic ⟨ł⟩, although pairs of words such as scóła, "school" and scóa, "broom" are homophonous (both being pronounced [ˈskoa]), they are still distinguished orthographically.

[40] Speakers of Italian generally lack this sound and usually substitute a dental [n] for final Venetian [ŋ], changing for example [maˈniŋ] to [maˈnin] and [maˈɾiŋ] to [maˈrin].

Compared to Italian, in Venetian syllabic rhythms are more evenly timed, accents are less marked, but on the other hand tonal modulation is much wider and melodic curves are more intricate.

The Academia de ła Bona Creansa – Academy of the Venetian Language,[citation needed] an NGO accredited according to the UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Venetian language and culture [43] [44] had already worked, tested, applied and certified a full writing system (presented in a scientific publication in linguistics [45] in 2016), known with the DECA acronym (Drio El Costumar de l'Academia, i.e. literally According to the Use of the Academia).

In more recent practice the use of ⟨x⟩ to represent /z/, both in word-initial as well as in intervocalic contexts, has become increasingly common, but no entirely uniform convention has emerged for the representation of the voiced vs. voiceless affricates (or interdental fricatives), although a return to using ⟨ç⟩ and ⟨z⟩ remains an option under consideration.

The hyphen or apostrophe is used because the combination ⟨sc(i)⟩ is conventionally used for the /ʃ/ sound, as in Italian spelling; e.g. scèmo (scemo, "stupid"); whereas ⟨sc⟩ before a, o and u represents /sk/: scàtoła (scatola, "box"), scóndar (nascondere, "to hide"), scusàr (scusare, "to forgive").

Recently there have been attempts to standardize and simplify the script by reusing older letters, e.g. by using ⟨x⟩ for [z] and a single ⟨s⟩ for [s]; then one would write baxa for [ˈbaza] ("[third person singular] kisses") and basa for [ˈbasa] ("low").

However, in spite of their theoretical advantages, these proposals have not been very successful outside of academic circles, because of regional variations in pronunciation and incompatibility with existing literature.

Overall, the system was greatly simplified from previous ones to allow both Italian and foreign speakers to learn and understand the Venetian spelling and alphabet in a more straightforward way.

The elderly narrator is recalling the church choir singers of his youth, who, needless to say, sang much better than those of today (see the full original text with audio): Sti cantori vèci da na volta, co i cioéa su le profezie, in mezo al coro, davanti al restèl, co'a ose i 'ndéa a cior volta no so 'ndove e ghe voéa un bèl tóc prima che i tornésse in qua e che i rivésse in cao, màssima se i jèra pareciàdi onti co mezo litro de quel bon tant par farse coràjo.

These old singers of the past, when they picked up the Prophecies, in the middle of the choir, in front of the twelve-branched candelabrum, with their voice they went off who knows where, and it was a long time before they came back and landed on the ground, especially if they had been previously 'oiled' with half a litre of the good one [wine] just to make courage.