Quaternary glaciation

[4] Since Earth still has polar ice sheets, geologists consider the Quaternary glaciation to be ongoing, though currently in an interglacial period.

The major effects of the Quaternary glaciation have been the continental erosion of land and the deposition of material; the modification of river systems; the formation of millions of lakes, including the development of pluvial lakes far from the ice margins; changes in sea level; the isostatic adjustment of the Earth's crust; flooding; and abnormal winds.

The ice sheets, by raising the albedo (the ratio of solar radiant energy reflected from Earth back into space), generated significant feedback to further cool the climate.

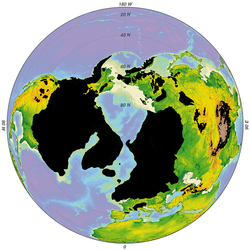

Over the last century, extensive field observations have provided evidence that continental glaciers covered large parts of Europe, North America, and Siberia.

Even before the theory of worldwide glaciation was generally accepted, many observers recognized that more than a single advance and retreat of the ice had occurred.

During the glacial periods, the present (i.e., interglacial) hydrologic system was completely interrupted throughout large areas of the world and was considerably modified in others.

[8] The role of Earth's orbital changes in controlling climate was first advanced by James Croll in the late 19th century.

According to the Milankovitch theory, these factors cause a periodic cooling of Earth, with the coldest part in the cycle occurring about every 40,000 years.

The main effect of the Milankovitch cycles is to change the contrast between the seasons, not the annual amount of solar heat Earth receives.

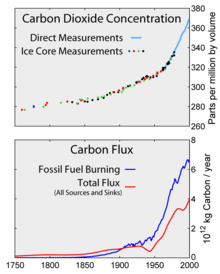

[12] Studies of deep-sea cores and their fossils indicate that the fluctuation of climate during the last few hundred thousand years is remarkably close to that predicted by Milankovitch.One theory holds that decreases in atmospheric CO2, an important greenhouse gas, started the long-term cooling trend that eventually led to the formation of continental ice sheets in the Arctic.

[15] Decreasing carbon dioxide levels during the late Pliocene may have contributed substantially to global cooling and the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

The Drake Passage opened 33.9 million years ago (the Eocene-Oligocene transition), severing Antarctica from South America.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current could then flow through it, isolating Antarctica from warm waters and triggering the formation of its huge ice sheets.

[23] This increased poleward salt and heat transport, strengthening the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation, which supplied enough moisture to Arctic latitudes to initiate the Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

Warmer temperature in the eastern equatorial Pacific caused an increased water vapor greenhouse effect and reduced the area covered by highly reflective stratus clouds, thus decreasing the albedo of the planet.

Propagation of the El Niño effect through planetary waves may have warmed the polar region and delayed the onset of glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere.

[31] Computer models show that such uplift would have enabled glaciation through increased orographic precipitation and cooling of surface temperatures.

Most obvious are the spectacular mountain scenery and other continental landscapes fashioned both by glacial erosion and deposition instead of running water.

[dubious – discuss] The numerous lakes of the Canadian Shield, Sweden, and Finland are thought to have originated at least partly from glaciers' selective erosion of weathered bedrock.

[36][37] The climatic conditions that cause glaciation had an indirect effect on arid and semiarid regions far removed from the large ice sheets.

Most pluvial lakes developed in relatively arid regions where there typically was insufficient rain to establish a drainage system leading to the sea.

The total uplift from the end of deglaciation depends on the local ice load and could be several hundred meters near the center of rebound.

Winds near the glacial margins were strong and persistent because of the abundance of dense, cold air coming off the glacier fields.

This dust accumulated as loess (wind-blown silt), forming irregular blankets over much of the Missouri River valley, central Europe, and northern China.

[45] Before the current ice age, which began 2 to 3 Ma, Earth's climate was typically mild and uniform for long periods of time.

This climatic history is implied by the types of fossil plants and animals and by the characteristics of sediments preserved in the stratigraphic record.

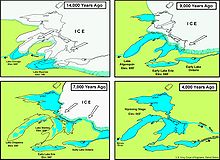

[47] The warming trend following the Last Glacial Maximum, since about 20,000 years ago, has resulted in a sea level rise by about 121 metres (397 ft).

The present interglacial period (the Holocene climatic optimum) has been stable and warm compared to the preceding ones, which were interrupted by numerous cold spells lasting hundreds of years.

However, slight changes in the eccentricity of Earth's orbit around the Sun suggest a lengthy interglacial period lasting about another 50,000 years.

2 since the Industrial Revolution